What the sciences discover about the natural world and about the origins, nature and destiny of man is the truth for religion. There is no other kind of valid knowledge. This natural knowledge, organized and applied to human fulfilment, is the basis of the new and permanent religion.

Julian Huxley, Religion Without Revelation (1927)

Grandson of ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ T.H. Huxley and brother to Brave New World author Aldous, Julian was another member of the Huxley family who made significant contributions to human understanding of the world around us.

A passionate naturalist, Huxley strove to bring the natural world closer to all humankind, and to improve our education in and understanding of the biological and cultural wonders in the world around us. He also believed that a knowledge of evolutionary biology could help humans to understand a greater part of themselves, and that our ethical framework should derive from ‘natural knowledge, organized and applied to human fulfilment’.

In both his roles as President of the British Humanist Association (today’s Humanists UK) and the first Director-General of UNESCO, Huxley was one of the most prominent proponents of rational, internationalist values and a rights-based social order.

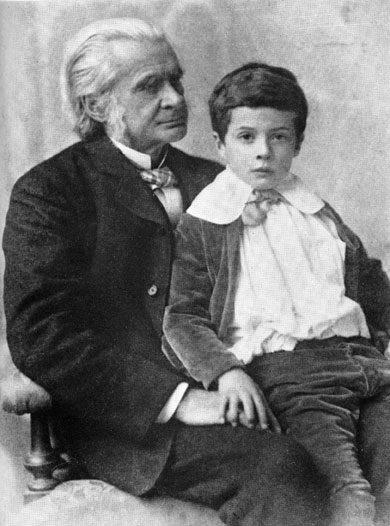

Born in 1887 to the biographer Leonard Huxley and the humanist educationalist Julia Huxley, the young Julian acquired his keen interest in the natural world from his grandfather, the leading biologist and advocate of Darwin’s theory of evolution T.H. Huxley. His passion for biological studies grew, and in 1906 he took up a place to study zoology at Balliol College, Oxford. After graduating with first class honours, the next few years saw him teach, study and write all across the world. He spent time in the United States and Germany, as well as assisting with the British war effort during the First World War as an intelligence officer in Northern Italy. The end of the war saw Huxley return to the UK to take up posts in university zoology departments. In 1927, however, he resigned his position with King’s College London to focus on producing a work called The Science Of Life, commonly regarded today as the first modern textbook of biology. Co-authored with H.G. Wells and his son, The Science Of Life aimed to introduce biological and ecological concepts to a popular readership, discussing such topics as animal classification, the history of evolution and even how biology overlaps with morality. The work was a huge success, and established Huxley as a gifted and influential populariser of science.

By the end of the 1920s, he was on his travels again. He spent time in East Africa, sharing his experience in the popularization of science with British colonial officials and assisting with the creation of national parks, alongside other conservation work. His skill as an educator and the depth of his knowledge of the natural world led him to be appointed as secretary of the London Zoological Society. He introduced many innovations during his tenure, such as the creation of Europe’s first petting zoo for children. Commonplace as this may seem to us, his changes caused friction between himself and the other, more conservative fellows of the Society and in 1942 he was removed from his post. Soon after, in 1945, he was appointed as the first director-general of UNESCO, an organisation set up in the aftermath of the Second World War which ‘seeks to build peace through international cooperation in Education, the Sciences and Culture’. Through UNESCO, Huxley had great scope to promote scientific education and the conservation of nature, and though his time as director-general was restricted to just two years, Huxley was able to set UNESCO on a bold and ambitious course.

Inspired as he was by the conviction that people are fundamentally in control of their own destinies, Julian Huxley found in humanism a natural framework for living one’s life. His studies in evolutionary biology showed him the link between biology and ethics, as well as our potential for physical and moral ‘progress’ based on a greater appreciation of our own autonomy. Huxley saw humanism as a replacement religion, grounded in values we can all recognize and benefit from. He served as the British Humanist Association’s first President from 1963 to 1965, and also worked closely with the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International), serving as its first President. In his unflinching pursuit of universal access to education and his work to conserve and protect the natural world, the strength of Huxley’s humanist ideals are laid bare. In a 1961 work he edited named The Humanist Frame, Huxley stressed the power and importance of humanism as an ethical structure for a modern humanity:

Humanism is seminal. We must learn what it means, then disseminate Humanist ideas, and finally inject them where possible into practical affairs as a guiding framework for policy and action.

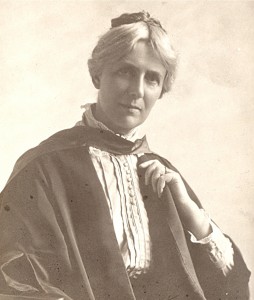

Mackenzie Hall is a community space in the village of Brockweir, Gloucestershire, given by Millicent Mackenzie in memory of her […]

The Liverpool Ethical Society was founded in 1904, and in 1912 Liverpool became home to one of only a handful […]

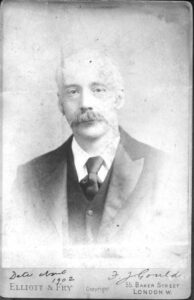

F.J. Gould was an influential educationist, writer, and humanist, whose tireless work towards secularising education helped to lay the groundwork […]

The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery primarily located in London but with various satellite outstations located elsewhere in […]