One might say that since retirement I have been reworking my paradigm. In that reworking I have reached conclusions, but as a humanist with a scientific training, I hold those conclusions lightly. It is a point of honour not to remain ‘true to my beliefs’. On the contrary: the honour lies — if you show me better — in changing… I have been modifying the software of my brain for all of my conscious life. I hope to be doing so until the day I die.

Justin Keating, Nothing is Written in Stone: the Notebooks of Justin Keating (2017)

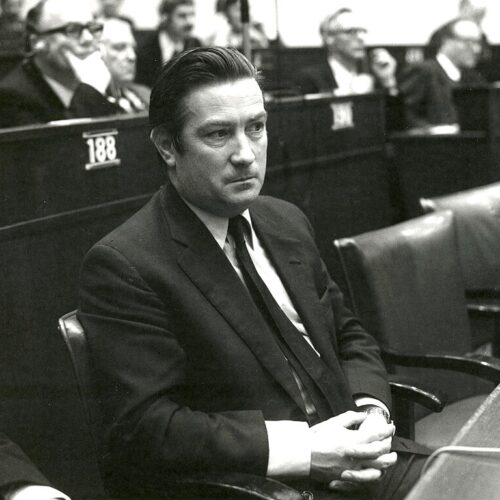

Justin Keating was a politician, veterinarian, and broadcaster, who lived his life guided by strong humanist principles and identified as a lifelong atheist and socialist. Influenced by his politically active parents, his humanism manifested early through involvement in political activism, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and later, the anti-apartheid movement. As a Labour TD and notably as Minister for Industry and Commerce (1973–7), he championed rational, state-led approaches to ensure the economy and natural resources served societal needs rather than private interests, challenging corporate power and advocating for public ownership. His commitment to human rights and secularism drove his support for the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and his calls for divorce and contraception rights in the Republic. Although initially opposing entry to the European Economic Community (EEC), he later embraced European federalism as necessary for global progress on ecology and peace. Keating’s humanism was explicit in his later years as President of the Humanist Association of Ireland (1998-2009), and his active promotion of humanist values through writing and events.

The biography reprinted below was first published in June 2015 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Maume, Patrick

Keating, Justin Pascal (1930–2009), politician, veterinarian and television presenter, was born 7 January 1930 in a nursing home at 37 Lower Leeson Street, Dublin, younger of two sons of Seán Keating, artist, and Mary Josephine ‘May’ Keating (née Walsh), political activist; the family resided at Killakee, Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin. Both Keating parents were socialists and republicans; their friends included Peadar O’Donnell and Dan Breen. May Keating played a decisive role in forming Justin’s political and religious views. Justin Keating was educated at Loreto Abbey primary school, Rathfarnham (contrasting his parents’ support for the Spanish Republic with his teachers’ pro-Franco views), and Sandford Park School, before studying veterinary medicine at University College Dublin. Keating had a brilliant academic career, taking honours and first place in all his examinations and winning numerous prizes; on graduation in 1951 he became the youngest veterinary surgeon in Ireland or Great Britain. He won the Evans studentship for the veterinary student with the best college record, which financed three years’ graduate research at the University of London, where he graduated B.Sc. in biochemistry. In January 1955 he was appointed as a lecturer in the section of the national veterinary college affiliated to Trinity College Dublin; he made research visits to France, Sweden and Denmark, and became lecturer in veterinary anatomy at TCD in 1960.

Keating had a brilliant academic career, taking honours and first place in all his examinations and winning numerous prizes; on graduation in 1951 he became the youngest veterinary surgeon in Ireland or Great Britain.

Early political commitments

In his late teens Keating became a Marxist and lifelong atheist. He formed a branch of the Irish Labour party in Rathfarnham in 1946, but resigned in 1948 in protest against Labour’s entering the newly formed inter-party government. At university he joined the Promethean Society, a Marxist body largely composed of Trinity students interested in the social implications of science and technology. He subsequently was active in the Irish Workers’ League (IWL), the country’s pro-Moscow communist organisation of the period, headed by Michael O’Riordan and influenced by the nationalist-Marxist C. Desmond Greaves. According to another Promethean and IWL activist, Roy Johnston, Greaves distrusted Keating, believing he downplayed his political commitments to secure academic employment in Ireland. Suspicion of Keating’s bona fides by socialist allies, fuelled by his non-proletarian origins and comfortable lifestyle, would beset his career. Keating remained active in Dublin liberal-left circles, demonstrating for the Irish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the early 1960s.

In his late teens Keating became a Marxist and lifelong atheist… Keating later denounced the Soviet regime but always remained a socialist, believing state power should ensure that the market served society rather than vice versa.

Keating’s marriage (1953) to Loretta Wine, an Irish-Jewish pianist, was another sign of social nonconformity. They had one son (the film director David Keating) and two daughters (Eilis, an accountant, and the historian Carla King). In 1957 Noel Browne used Keating’s communist links to justify a ‘red scare’ purge of supporters (including May Keating) whom Browne considered insufficiently submissive. Keating later denounced the Soviet regime but always remained a socialist, believing state power should ensure that the market served society rather than vice versa.

Television presenter, TD and anti-EEC campaigner

After the establishment of an Irish television service in 1961, Keating appeared frequently on discussion programmes, and on the radio programme Farmers’ forum. He worked extensively during the 1960s with the Irish Co-operative Development Trust, seeking a means of improving production while preserving rural society, while praising the critique of Raymond Crotty of the structure of Irish farming and regretting that the advocacy by Michael Davitt of land nationalisation had been defeated by peasant proprietorship. Keating took leave from TCD to become head of agricultural programmes at RTÉ (1965–7). His primary commission was to produce and present Telefís feirme, an adult education programme for farmers run in conjunction with local study and discussion groups. Each of the forty-eight episodes consisted of a twenty-minute lecture by Keating, with innovative graphics by Gerrit van Gelderen and imaginative props. Keating also wrote and presented the series On the land and Surrounded by water (on Ireland’s potential sea resources). After returning to TCD in 1967, Keating still worked on occasional programmes on RTÉ; he presented and partially wrote the thirteen-episode Into Europe (1968), outlining contemporary developments in various European countries, and presented the series Work. He also was a freelance presenter on the BBC. He was active in the anti-apartheid movement and in agitations to preserve historic housing in Dublin city centre as residential accommodation rather than allowing its demolition by speculative office developers.

He was active in the anti-apartheid movement and in agitations to preserve historic housing in Dublin city centre as residential accommodation rather than allowing its demolition by speculative office developers.

In November 1967 Keating was recruited by the Labour party. His candidacy for Dublin County North in the 1969 general election reflected the ongoing effort by the party leadership under Brendan Corish to field prestigious and televisually-skilled leftist intellectuals (others being David Thornley and Conor Cruise O’Brien), as well as an (unsuccessful) strategy to secure rural support. During the campaign Fianna Fáil diverted Labour attacks on dubious land transactions between Minister for Finance Charles J. Haughey and the developer Matt Gallagher by claiming that Keating’s recent sale of his land in Tallaght amounted to property speculation. Keating produced documentary proof that he sold to Dublin Corporation for social housing at a lower price than offered by a private developer.

Elected Labour TD for Dublin County North (1969–77), Keating rapidly emerged as a leading spokesman for the party… Keating was strongly supportive of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, arguing that the developing northern conflict was not a local dispute but derived from British imperialism, which enmeshed the republic as well as the north. He argued the republic should prepare for unity by recognising divorce and contraception as civil rights.

Elected Labour TD for Dublin County North (1969–77), Keating rapidly emerged as a leading spokesman for the party. He claimed that the apparent economic successes of the era of Seán Lemass were achieved by selling Irish assets to multinational companies caring nothing for Irish long-term development, which could only be guaranteed by a greater role for the state sector. Keating declared that, since the departure of Éamon de Valera, Fianna Fáil had become flamboyantly corrupt, and its underlying authoritarianism was shown in harsh legislation against ‘squatting’ in unoccupied buildings by housing protestors, and attacks on the independence of RTÉ and the National College of Art and Design. Keating was strongly supportive of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, arguing that the developing northern conflict was not a local dispute but derived from British imperialism, which enmeshed the republic as well as the north. He argued the republic should prepare for unity by recognising divorce and contraception as civil rights. Keating was close to John Hume and the more nationalist wing of the SDLP, which favoured British–Irish joint authority over Northern Ireland; he developed fierce mutual hostility with the increasingly pro-unionist O’Brien. Keating denounced the IRA and the involvement of Fianna Fáil ministers in the 1970 arms crisis, but in 1971 resigned from the dáil public accounts committee inquiry into the arms crisis, claiming that Taoiseach Jack Lynch and his defence minister, Jim Gibbons, knew of the arms smuggling activities of Captain James Kelly – whom Keating always regarded as an honest scapegoat – much earlier than they admitted.

He advocated European federalism, claiming… Europeans could only preserve the ecology of the planet, restrain weapons of mass destruction and maintain reasonable living standards through a continental bloc exerting influence at global level.

In the national debate preceding the 1972 referendum on Irish membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), Keating was the most outspoken front-rank political opponent of entry; he argued that the EEC was a neo-imperialist force which would entrench a narrow European banking and financial elite beyond democratic accountability while exploiting developing countries, and that Irish industry and agriculture were grossly unprepared for European-wide free trade. Keating admitted that long-term isolation was economically and politically unsustainable, but argued that associate EEC membership would give Ireland the advantages of membership while allowing reorganisation of agriculture and industry on a cooperative basis. At times Keating seemed to admit that Irish EEC membership might be unavoidable, and after the referendum showed a 5 to 1 majority in favour he accepted the fait accompli and became a nominated member of the European Parliament (December 1972–June 1973). In later life Keating maintained that accession to the EEC had been the best decision ever taken by the Irish people, providing a major drive for modernisation and equality. In subsequent European referenda he advocated European federalism, claiming small states were now powerless and Europeans could only preserve the ecology of the planet, restrain weapons of mass destruction and maintain reasonable living standards through a continental bloc exerting influence at global level.

Cabinet minister; natural resources policy

In the Fine Gael–Labour national coalition government formed after the 1973 general election, Keating was minister for industry and commerce (1973–7). He was regarded by officials and by journalists (such as Dick Walsh) as an exceptionally hardworking and decisive minister with a clear strategy; his difficulty was putting it into practice.

He was regarded by officials and by journalists as an exceptionally hardworking and decisive minister with a clear strategy; his difficulty was putting it into practice.

The new cabinet was riven by personal rivalries, intermixed with ideological disputes and crossing party lines. Keating faced hostility from Labour cabinet colleagues O’Brien, Michael O’Leary and James Tully, but worked closely with Fine Gael Minister for Foreign Affairs Garret FitzGerald, a personal friend. Keating’s assertion of the traditional Industry and Commerce claim to jurisdiction over foreign trade meant that he regularly attended meetings of the EEC Council of Ministers with FitzGerald. Brian Harvey has argued that FitzGerald, Keating and Minister for Finance Richie Ryan, as the only ministers acquainted with modern economics, exercised disproportionate influence over the coalition’s economic policy in a social-democratic direction uncongenial to some right-wing colleagues. Keating and FitzGerald also shared scepticism about the more illiberal aspects of the government’s security policy, and in 1976 FitzGerald supported Keating’s unsuccessful attempt to be named Ireland’s European commissioner rather than Fine Gael nominee Richard Burke.

Although Keating restructured the Industrial Development Authority to adjust to EEC membership, it failed to create sufficient jobs to replace losses in the recession triggered by the 1973 oil crisis. The crisis and other pressures within the world economy caused runaway inflation, reaching 20 per cent at one point; Keating was widely blamed, though it was largely beyond his control.

Keating’s term in office was dominated by arguments over the ownership and exploitation of Irish natural resources, entangled with the dispute between the Labour party leadership and left-wing anti-coalitionists led by Noel Browne, who regarded opponents… as cowards and renegades.

Keating’s term in office was dominated by arguments over the ownership and exploitation of Irish natural resources, entangled with the dispute between the Labour party leadership and left-wing anti-coalitionists led by Noel Browne, who regarded opponents (particularly Keating, for whom Browne developed intense personal hatred) as cowards and renegades.

In 1971 a large lead-zinc orebody was discovered at Navan, Co. Meath, by Tara Mines, owned by multinational companies. Most of the land was owned by the state, but one-sixth belonged to a local farmer who sold his mineral rights to Bula, a company newly formed by Irish businessmen. Keating sought to acquire a large state interest in the mines, and replaced Fianna Fáil legislation giving mining companies a twenty-year tax holiday on new discoveries with a regime involving royalty payments on declared profits. He secured a 49 per cent state holding in the Bula company for £9.54 million – criticised as unreasonably high, though set by an independent arbitrator. Keating claimed this Bula stake was crucial for his acquisition of 25 per cent of Tara, accompanied by favourable royalties terms and an agreement that the company would construct a smelter; most observers argued he could have achieved these anyway as a condition for granting a state mining licence to Tara. Keating initially tried to persuade Tara and Bula to merge; his consistent aim was to create an Irish multinational with significant state involvement which could compete within the global mining industry. Dáil debates on the Bula deal were remarkably bitter, with accusations of communism and corruption exchanged. Fianna Fáil frontbencher Desmond O’Malley argued in a series of forceful speeches that the state’s interest would be better served by securing tax revenues from private owners rather than the costly and financially risky strategy of co-ownership.

Falling zinc prices caused the Tara mine to run at a loss for most of its first decade (leading to cancellation of the smelter); in 1988 the government sold its shareholding and royalty rights to the Finnish state mining company Outokumpu (which had acquired the rest of Tara). Bula was crippled by delays in obtaining planning permission and related problems; it went into receivership and its assets were acquired by Tara. In 1986 Keating successfully sued the Sunday Tribune newspaper after it published an article widely interpreted as meaning Keating’s dealings with Bula were corrupt. Keating won IR£65,000 damages, a record at the time.

Keating pursued a similar strategy in the oil and gas industry of state involvement aimed at creating an internationally competitive state energy company resembling the Italian ENI or the Norwegian Statoil. In 1975 he laid down terms for oil and gas exploration off the Irish coast requiring companies to give the Irish state 50 per cent of any commercial find, pay royalties of 6 to 7 per cent with a bonus on significant finds, pay 50 per cent corporation tax, drill at least one well in three years, and surrender 50 per cent of the area covered by their licence within four years. Keating assumed that energy prices (increased substantially by the 1973 oil crisis) would continue to rise, making it worth the industry’s while to develop the risky and inaccessible Irish Atlantic seabed, and that significant reserves would be discovered. Over the next decade, oil companies drilled ninety-eight wells costing £400 million; declining oil prices and failure to make major discoveries led Labour industry minister Dick Spring to water down Keating’s terms in 1985 and 1986. In 1987 the Fianna Fáil minister Ray Burke exempted oil and gas production from royalty payments and provided extensive tax write-offs; in 1992 Bertie Ahern, as minister for finance, provided further tax concessions. In the early twenty-first century various groups and individuals have argued that Keating’s policy towards oil and gas exploration should be revived.

Out of politics; last decades

In the 1977 general election he was defeated in the new Dublin County West constituency… Shortly after the 1977 election, he was diagnosed with Paget’s disease, a degenerative bone condition causing deafness, heart damage and balance problems.

Keating believed that as TD and minister his function was to legislate and make policy, and delegated constituency work to a secretary; this demoralised his constituency organisation. In the 1977 general election he was defeated in the new Dublin County West constituency. A member of Seanad Éireann on the agricultural panel (1977–81), he advised party leaders on economic matters but was not part of Labour’s decision-making core. Shortly after the 1977 election, he was diagnosed with Paget’s disease, a degenerative bone condition causing deafness, heart damage and balance problems; for a time, early death was predicted. After his health problems were contained, Keating decided to leave public life to spend more time with family, friends and the pedigree Frisian herd on his 280-acre Kildare farm. In February 1984, however, he was nominated to a Labour seat in the European Parliament for Leinster, replacing Carlow–Kilkenny TD Séamus Pattison (appointed a junior minister). Keating was defeated in the June 1984 European elections, his last electoral contest. The Labour Party later tried unsuccessfully to persuade the FitzGerald government to nominate Keating as European commissioner.

In 1984 Keating became president of the National Council for Educational Awards. He resigned from TCD in the late 1970s but remained an active veterinarian, developing an innovative course in equine management at the University of Limerick and joining the board of the Irish Equine Centre in 1993. He also presented occasional RTÉ television programmes, including a short-lived 1983 discussion show, Keating on Sunday. He was president of the National Crafts Council of Ireland and promoted his father’s artistic reputation. He also promoted Irish food culture and cookery (he was an enthusiastic amateur chef) and advocated the development of Irish specialist food brands.

In 1984 Keating became president of the National Council for Educational Awards. He resigned from TCD in the late 1970s but remained an active veterinarian, developing an innovative course in equine management at the University of Limerick and joining the board of the Irish Equine Centre in 1993.

Continuing to comment on public affairs, Keating grew more outspoken as he got older. He blamed British intransigence for the impact of the 1981 Maze hunger strikes, and suggested that the survival of Irish democracy in this crisis indicated that official fears in the 1970s of destabilisation were overblown. In 2003, after the Barron report suggested that British security elements colluded in the 1974 loyalist bombings of Dublin and Monaghan, Keating speculated that an inner axis of security-minded ministers in the Cosgrave cabinet had suppressed the investigation as endangering the state. Keating was president of the Association of Irish Humanists (latterly, the Humanist Association of Ireland) from 1998 until his death, addressing Darwin Day celebrations and the annual Humanist Summer School in Carlingford, Co. Louth, and writing regularly for the Irish Humanist (from 2008, Humanism Ireland, after merging with its Northern Ireland counterpart). After revelations of historic mistreatment of child inmates in institutions run by catholic religious orders, Keating repeatedly apologised to abuse survivors on behalf of the government in which he served. Keating supported Zionism as a young man, but in his last decades was outspokenly anti-Zionist, denouncing Western intervention in the Arab and Islamic world, and criticising stereotyping of Muslims and Islam.

Keating was president of the Association of Irish Humanists (latterly, the Humanist Association of Ireland) from 1998 until his death, addressing Darwin Day celebrations and the annual Humanist Summer School.

Keating’s marriage ended in 1991; he remained on friendly terms with Loretta, who later remarried. For the last seventeen years of his life his partner was Barbara Hussey, a solicitor, whom he married in 2005; they had no children. Justin Keating died suddenly at his home in Ballymore Eustace, Co. Kildare, on 31 December 2009, and after a humanist funeral was buried in a biodegradable coffin.

Keating attracted intense attachment and admiration, often in succession from the same people. Opponents frequently accused him of deliberate bad faith. In fact, he held a coherent and consistent worldview; his problem was its implementation.

GRO (birth cert.); Ir. Times, 15, 16 Feb. 1960; 23, 24 June, 11, 16 Dec. 1965; 20 Jan. 1966; 21 Jan., 4 Mar., 18, 27 May, 21 Nov. 1967; 3, 22 Feb., 14, 22 Mar., 18 July 1968; 21 Jan., 14 Feb., 12, 14, 24 Apr., 2 May, 3, 6, 13, 14, 17, 28 June, 18 Aug., 15 Sept., 23 Oct., 15, 19, 25, 26, 27, 29 Nov. 1969; 19 Jan., 16 Feb., 11, 14, 17, 23, 31 Mar., 13, 30 Apr., 2, 7, 9 May, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 17 June, 8, 9, 25, 31 July, 22 Aug., 21, 28 Sept., 3, 16, 29 Oct., 5, 12, 18, 19, 25, 26 Nov., 2, 11, 14, 17 Dec. 1970; 12, 17 Feb., 1, 3, 4, 12, 29 Mar., 25 May, 2, 3, 9, 30 June, 7, 10, 17, 21 July, 6 Aug., 3, 4 Nov., 3, 4 Dec. 1971; 17 Sept. 1983; 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 17 Dec. 1985; 15 Feb., 19, 26 Apr., 20 June, 14, 17 July, 20 Aug., 17 Sept., 6 Dec. 1986; 6, 20 Apr., 1, 3 Oct. 1987; 27 Oct. 1988; 11 Jan., 8 May 1989; 23 Mar., 21 Apr., 17 July 1990; 29 Mar., 13 July 1991; 22, 23, 27 Mar., 2, 6 Oct., 26 Nov., 2 Dec. 1993; 9 June, 2, 27 July 1994; 20 Feb., 30 Dec. 1995; 29 June, 30 Nov., 7 Dec. 1996; 7, 19 Feb. 1997; 4, 22 May 1998; 22 May, 15 July 1999; 15 Jan., 28 Feb., 15 June, 8, 13 July 2000; 2 Nov. 2001; 26 Feb., 30 Sept., 3, 26 Oct. 2002; 8 Jan., 8 Feb., 21 July, 12, 29 Dec. 2003; 5, 14, 17 Jan., 3 Mar., 3, 26 Apr., 26 Aug., 5 Nov. 2004; 29 Jan., 16 Feb., 15 Aug. 2005; 29 May 2006; 2 Aug., 31 Dec. 2007; 13 Feb., 20, 30 Dec. 2008; 24 July 2009; 2, 4, 5, 6, 11, 22 Jan., 17 Feb. 2010; 16 June, 5 July 2012; Ir. Press, 27 Oct. 1965; 30 Nov. 1968; 13, 14, 18 June 1969; Irish Farmers’ Journal, 21 May, 17 Nov. 1966; Ir. Independent, 1 Apr. 1967; 12 Apr. 1969; Brian Harvey, Cosgrave’s coalition (1978); Vincent Browne and Michael Farrell (ed.), Magill book of Irish politics (1981), 138–9; Michael Gallagher, The Irish Labour party in transition, 1957–82 (1982); John Horgan, Labour: the price of power (1986); Garret FitzGerald, All in a life: an autobiography (1991); Fergus Finlay, Snakes and ladders (1998); Conor Cruise O’Brien, Memoir: my life and themes (1998); Barry Desmond, Finally and in conclusion: a political memoir (2000); John Horgan, Noël Browne: passionate outsider (2000); Roy Johnston, A century of endeavour (2003); Ruairí Quinn, Straight left: a journey in politics (2005); Niamh Purséil, The Irish Labour party 1922–73 (2007); David McCullagh, ‘“A particular view of what was possible”: Labour in government’ in Paul Daly, Rónán O’Brien and Paul Rouse (ed.), Making the difference: the Irish Labour party 1912–2012 (2012); Eunan O’Halpin, ‘Labour and the making of Irish foreign policy, 1973–77’ in ibid.; Sunday Independent, 3 Jan. 2010

Main image: Justin Keating, Strasbourg session, January 1973 © Communautés européennes 1973

The House of Commons refused to allow his affirmation, so Bradlaugh applied to take the oath but was again refused. […]

What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other? George Eliot, Middlemarch […]

Bishopsgate Institute was built ‘for the benefit of the public’ in 1894, intended to provide opportunities for education and recreation […]

Without this mutual trust and dependability amongst people who differ radically, there cannot be political and religious freedom. H.J. Blackham […]