It was the start of opening up society to be more caring and sensitive. One was battling for all men and women to have a greater freedom.

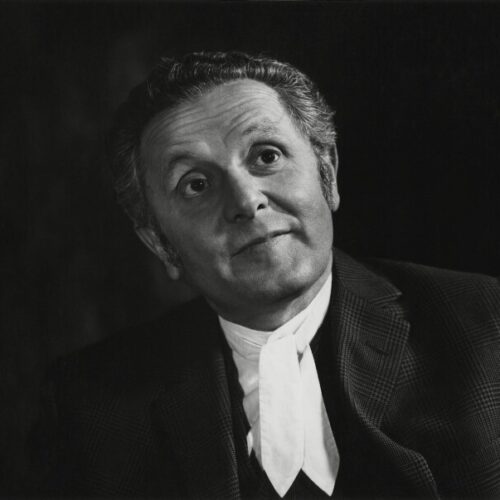

Leo Abse, 2007

Leo Abse was a politician and lawyer who, in a parliamentary career spanning three decades, worked tirelessly to achieve liberalising reforms in homosexuality and divorce laws. Abse became known as one of the 20th century’s most significant social reformers, his efforts underpinned not by any religious belief, but instead by a humanist commitment to human wellbeing and social equality.

Leo Abse was born in Cardiff on 22 April 1917. His grandparents had moved to Wales from Germany and Poland in the 1880s, and he was raised by his parents in a secular Jewish household. After briefly working in a factory Abse went on to study Law at the London School of Economics, and proved a very capable, dedicated student. The Second World War diverted his efforts for a time, and Abse served with the Royal Air Force. His natural instinct for activism and debate bore fruit in the ‘forces parliament’ which had been set up by military personnel to discuss politics and the post-war society. Abse was one of the more vocal members of the forces parliament, and his credentials as a rebel were sealed when he was ordered back to Britain from Egypt in 1944 after calling for a motion which was deemed too radical (the nationalisation of the Bank of England). Despite this, he returned to practising law after the war, eventually establishing the legal firm Leo Abse & Cohen in 1951. The firm would grow to become one of the largest in Wales, making Abse a wealthy man. Despite this, he remained committed to his radical, socialist principles.

Abse had been a political radical before he joined the forces parliament, and continued long after it was disbanded. He first joined the Labour Party in 1934 and was chairman of Cardiff Young Socialists. While working as a solicitor after the Second World War he became Chairman of the Cardiff City Labour Party, and after standing for parliament unsuccessfully in 1955 he was eventually elected in 1958 as the MP for Pontypool. His eccentric style and his gifts as an orator left an instant impression on his peers, and though he remained a back-bench MP throughout his political career, he was a well-respected and influential figure. Being a back-bench MP with no intentions of serving at a cabinet level earned Abse sufficiently more freedom to pick his battles than many of his fellow MPs. This sometimes saw him come into conflict with the Labour frontbench, such as in his fierce opposition to James Callaghan’s proposals for devolution.

This political freedom, however, also granted Abse the ability to pursue the causes he was most passionate about. He was a staunch advocate for the decriminalisation of homosexual activity between consenting males, as well as pushing for the simplification and liberalisation of divorce laws. After suffering initial setbacks for both of these reforms, Abse’s tenacity eventually saw both measures written into law in the late 1960s. Other liberalising societal reforms were driven through in the following years, largely thanks to Abse’s efforts. The laws around fostering and adoption were simplified and children were finally able to seek details of their birth parents; local authorities were permitted to distribute contraceptives and open birth-control clinics; and Abse also played a large role in the eventual abolition of capital punishment in the UK. Few politicians of the 20th century can claim to have had as big a hand in helping create a more liberal, tolerant society than Leo Abse.

After serving his constituency for thirty years, Abse retired as an MP in 1987. Despite not being granted a peerage as many had expected, he remained politically active, penning a number of books on subjects ranging from Britain’s relationship with Germany to psycho-analytical biographies of Margaret Thatcher and, latterly, Tony Blair, neither of which were particularly flattering to their subjects. Despite his declining health, Abse continued to court controversy and thrived on saying things which few others felt able to. This trait may not always manifest itself in the most popular ways, but it is undeniable that the conviction to stand up for what one believes to be right in the face of criticism and longstanding orthodoxy is a noble and necessary component of progress, without which the rights and livelihoods of so many people would remain unprotected.

All Abse’s bills related to human relationships and social welfare — divorce, women’s rights, widows’ damages, family planning, industrial injuries, his groundbreaking 1967 bill on homosexuality and, perhaps most crucial of all, the Children Act (1975), which dealt with fostering and adoption. He initiated the first Commons debates on genetic engineering and in-vitro pregnancies.

Geoffrey Goodman for The Guardian, 2008

Right up to his death in 2008, Abse passionately believed in a liberal, peaceful society where everybody’s rights are defended and celebrated. A great many practices and attitudes we in the UK take for granted today are in no small part due to the tireless work of Leo Abse.

Abse was a vocal admirer of Nye Bevan, and many of his reformist efforts recall earlier ones by humanists throughout history, including May Seaton-Tiedeman in her tireless campaign for divorce law reform during the early 20th century. So too do they mirror and anticipate the past and present work of Humanists UK in seeking rational reforms for a more tolerant, compassionate society.

Lift the heart to high endeavour! Fire the thought and nerve the will! Though the bonds be hard to sever, […]

Now art, certainly literary art, is ‘existential’ and has to be so. It is, if nothing else, about the real […]

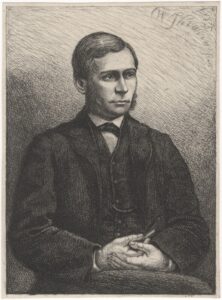

Thomas Hill Green was a philosopher, educator, and a Liberal, whose idealist philosophy (with its practical implications) was a significant […]

Humanists UK began as the Union of Ethical Societies in 1896, becoming the Ethical Union in 1920, the British Humanist […]