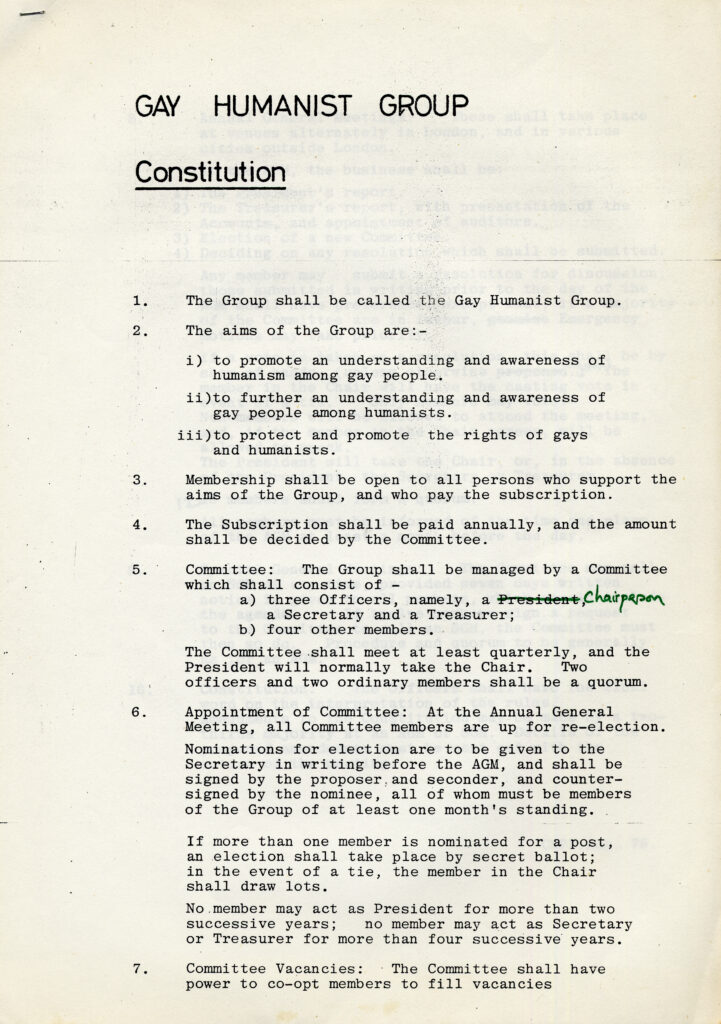

Formed in the wake of the Gay News blasphemy trial, GALHA (now LGBT Humanists) came into being in 1979 as the Gay Humanist Group. For 45 years it has been on the side of equal rights and free speech, campaigning for both with a philosophy underpinned by rationalism and what writer and inaugural president Maureen Duffy described as ‘an ethics of compassion.’

When Mary Whitehouse brought her prosecution for blasphemous libel against Gay News in 1976, it was the first charge of its kind for over half a century. Whitehouse was reacting to the publication of a poem by James Kirkup entitled ‘The Love That Dares to Speak Its Name’, depicting the love of a Roman Centurion for a recently crucified Jesus. The backlash she received led Whitehouse to suggest that an ‘intellectual/homosexual/humanist lobby’ was to blame, a comment that did not escape the attention of members of this as yet non-existent group.

‘That there was no such lobby and the obvious fear that such an idea provoked provided the spark which convinced us that the opportunity offered to a gay Humanist group was too good to miss,’ wrote founding member George Broadhead of the group’s nucleus. The group launched officially at the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) Brighton Conference in August 1979. Later, fellow founders Barry Duke and Brian Parry would explain what seemed to be a logical pairing of the humanist and gay causes, writing that ‘[b]y fighting ignorance, superstition, dogma and bigotry, the Gay Humanist Group [hoped] to encourage more gays and humanists to come out and declare themselves and their convictions with pride.’

Even in the face of overt bigotry, and as part of continuous activism, there is a wry humour which characterises many of the group’s newsletters and press pieces, kept today in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute. This, as well as Duffy’s concept of an ‘ethics of compassion’ is evident throughout. Maureen Duffy, the group’s honorary president, defined this in a 1980 address as ‘a fluid morality, based on a perception of fellowness, fellow feeling, fellow suffering.’ But this compassionate attitude would support a deep desire for change, and a willingness to fight for it: ‘One very important aim for this association is to speak up wherever necessary from the rationalist stance’. This was echoed by Chris Findlay in a newsletter a year later, when he called on GHG not to lose the momentum of their first year, continuing ‘to play a strong part in campaigning for gay rights, using the piercing weapons of reason and science against the ignorance, superstition and blind faith that sustains the prejudice against homosexuals’. And this they did.

Among the methods employed to lobby and campaign was the creation of a Postal Action Group, through which members could be implored to ‘lobby MPs, government ministers, commercial firms and the media on dozens of issues relating to gay and Humanist rights’. GALHA also maintained a strong tradition of international interest, lobbying Amnesty to better assist LGBT people in countries across the world and working, after becoming members in 1983, as part of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International) for greater compassion everywhere.

Over the following years, the Gay Humanist Group (which became the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association in 1987) worked for change, inclusivity and celebration. The archives testify to interactions with numerous other active groups, also working for a more tolerant society. These have included Stonewall, Exit (as the Voluntary Euthanasia Society, now Dignity in Dying, was known 1979-82), Feminists Against Censorship, Outrage!, and the Terrence Higgins Trust.

Celebrating their ten-year anniversary, Antony Grey, former secretary of the Homosexual Law Reform Society wrote to congratulate GALHA: Constantly having to combat irrational and dangerous thinking is strenuous and sometimes tedious, but not necessarily boring. It can be fun. And as no-one else is doing it as consistently and effectively as is necessary. I hope that GHG will concentrate on a demolition job of much of the silly rubbish that is still spouted about homosexuality.

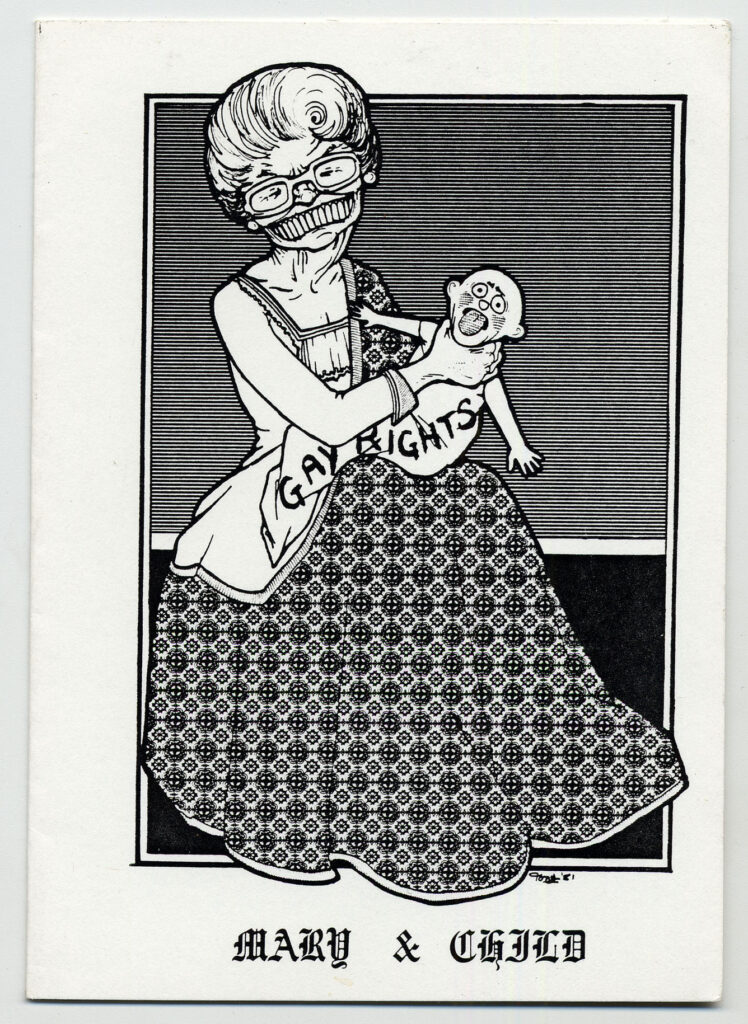

A glance through GALHA’s collected press releases and calls to action offers just a flavour of this ‘demolition job’. Over the years, members wrote to condemn the homophobic dismissal of John Saunders from his job at a Scottish youth camp, called for the abolition of the blasphemy law, campaigned for equal age of consent, protested Christian ‘cure’ ministries, and slammed prejudice and bigotry everywhere from school boards to the armed forces. At the same time, they produced alternative Christmas cards, educational pamphlets, and the long running Gay Humanist.

Letters in the collection also testify to the causes taken up by GALHA. A recurring theme throughout their archive is a concern over the accuracy of representation in the press; not just for the proponents of equality but so too for those supporting (or proposing) restrictive measures. In letters to Jim Herrick, MP David Wilshire and Bishop Ross Hook (writing on behalf of the Archbishop of Canterbury) are both at pains to suggest that Herrick has misunderstood their position as a result of its media misrepresentation, press reports being ‘necessarily abbreviated’. In 1988, Wilshire sought to clarify that his introduction of Section 28 was not homophobic, assuring Herrick that: ‘no criticism of homosexuality is made… [it] simply seeks to do three things: Put an end to local authorities promoting homosexuality; halt the teaching of homosexuality as a pretend family relationship; and stop the use of rate-payers money to enable others to do these things.’ Only eventually repealed in 2003, from its initial proposal Section 28 was fiercely resisted by GALHA and many associated humanist and LGBT groups, including through tireless lobbying and demonstrations.

In keeping with the spirit of their instigation, in 1989 GALHA publicly offered its ‘unequivocal’ support for Salman Rushdie following accusations of blasphemy and death threats from Islamic fundamentalists and vehemently opposed ‘proposals to extend the law of blasphemous libel to protect Islam or any other religion’. At Conway Hall, where GALHA had held its meetings from the beginning, the South Place Ethical Society staged a public reading of extracts from the Satanic Verses in support of Rushdie and the cause of free speech.

1989 also marked ten years of GALHA, which saw Conway Hall’s library ‘transformed beyond recognition by masses of pink balloons and streamers’. Angela Williams, journalist, humanist, and editor of the problem page for Women’s Own, sent the group a letter of congratulations:

This decade of campaigning and support for gay rights can’t have been easy. There are some grisly challenges. New prejudices and bigotry have crawled out of the woodwork – or maybe it’s just the old ones given new acceptance and approval. But you have survived and you’re in good heart. I send you my congratulations and my warmest good wishes for the next ten years.

In gratitude to Conway Hall, GALHA presented them with a portrait of E.M. Forster painted by his cousin Philip Whichelo and donated to the group, which can still be seen in the library today.

GALHA’s efforts for those ten years and beyond were not merely in dismantling and disagreement – they were also pioneering in their offer of secular ceremonies of all kinds. In the face of ‘the backlash against lesbians and gays from reactionary forces capitalising on the AIDS crisis’ GALHA organised, promoted, and performed affirmation ceremonies for gay couples, from the hippodrome to the hearth-rug. Particularly notable was the 1987 live broadcast of such a ceremony (with a script provided by GALHA) on Network 7, featuring, as described by George Broadhead ‘the first close-up gay smootcher on TV’. This script was used again for a mass gay wedding held at London’s Hippodrome nightclub, and in many more across the UK.

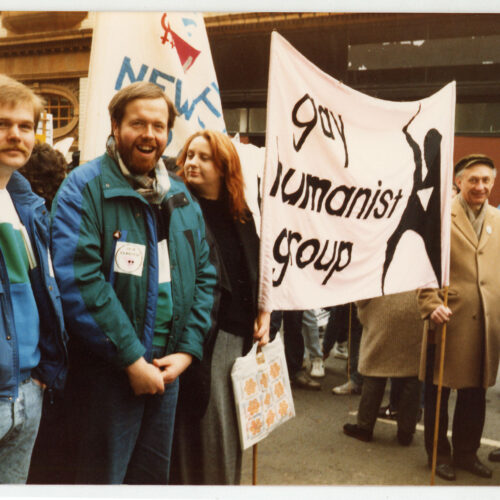

GALHA has also long provided a space for its members to find community and to have fun. As well as being a regular feature at Pride marches and political demonstrations from its earliest days, GALHA members have gathered socially in locations from Brighton to Lakeland, and have been represented by regional groups across the country. Today, as LGBT Humanists, the group continues its trail-blazing work – including on an international scale – to challenge homophobia and fight for human rights.

Through the 1990s and into the 2000s, GALHA continued both to campaign for equality and to provide ‘matches, hatches, and dispatches’ to those seeking non-religious celebrations of life and love. These have ranged from the 1994 humanist funeral of figure skater and Olympic medal winner John Curry to ‘watery weddings’ and naming ceremonies conducted by humanist celebrants.

In spite of paving the way for the eventual recognition of same-sex marriages in the UK, there is still work to be done for marriage law reform. Though same-sex marriages have been recognised, and despite the growing popularity of humanist ceremonies across the UK, humanist weddings are not yet, as of 2024, legally binding in England and Wales. This is one more cause taken up by humanists across the board today.

No law can be effective which has not behind it the sanction of the people. Dorothy Thurtle, quoted by David […]

While much of the Humanist Heritage website looks back to the earlier years of the organised humanist movement, recent decades […]

Mary Holland was a doyenne of Irish journalism. She epitomised the highest journalistic standards – she inquired, she informed, she […]

I agree that faith is essential to success in life (success of any sort) but I do not accept your […]