Is it not the duty of every person to promote the happiness of others as much as lies in their power?

Mary Ann Mccracken, October 1797

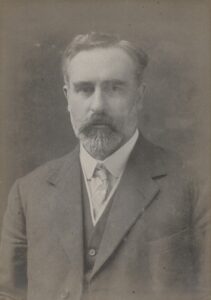

Mary Ann McCracken was a tireless social reformer, abolitionist, and feminist. Against a background of sectarianism and rampant discrimination upon religious grounds, McCracken’s extensive social work was deliberately non-denominational, looking instead towards a more secular future for Northern Ireland, involving all and discriminating against no one. As such, McCracken is part of that strand of humanist heritage which stands firmly against discrimination or persecution on religious grounds, and works instead for a society in which citizens are treated with compassion by their leaders, and by one another.

Mary Ann McCracken was born in Belfast to prosperous merchant parents, the fifth of seven children. The family were Presbyterian, and Mary Ann attended a co-educational school under the progressive leadership of David Manson, whose ideas of the teacher’s duty ‘to gain the affection and confidence of the children under his care; and make them sensible of kindness and friendly concerns for their welfare’ were deeply formative.

As outsiders to the established church of Ireland, Presbyterians – though commercially successful – were without political power or representation, and barred from inclusion in many areas of public life. These injustices shaped McCracken’s firm sense of right and wrong, and of every individual’s personal responsibility for the welfare of others. So too did the writings of figures such as Thomas Paine, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft:

While Mary McCracken was by no means the only young woman in the town familiar with the writings of Rousseau, Godwin, Mrs. Barbauld, and the rest, her uniqueness lay in the fact that, to a far great extent than any of her contemporaries, she translated these ideas critically and selectively, from the realm of theory to the needs of her own surroundings.

Like others of her generation, Mary Ann witnessed the influence of the American, French, and Industrial Revolutions on the radical and progressive hopes of many in the north of Ireland at the time; Belfast itself became a hotbed of radical activity. Central to this were The United Irishmen, of which McCracken’s brother Henry Joy (‘the handsome rebel’) was a founding member, and who was later imprisoned and executed for his role in the rebellion. On his death, Mary Ann, in defiance of both convention and the wishes of her family, took in Henry Joy’s illegitimate daughter, Maria. In so doing, she demonstrated a strength of character and sense of personal morality outside of – and beyond – the religion in which she had been raised.

In 1814, McCracken became a member of The Belfast Charitable Society, focusing her efforts on improving the lives of children, the sick, and the elderly. A devoted worker for political and social reform, McCracken could, approaching her nineties, be seen on the Belfast docks handing out anti-slavery pamphlets to those coming and going on the ships.

Mary Ann McCracken died on 26 July 1866 at the age of 96. She was buried in Clifton Street Cemetery, Belfast.

A woman of strong character and generous sympathies, with a ready pen and a forthright mind.

R. B. McDowell

Mary Ann McCracken represents a key moment in the development of Irish secularism. Through a life both traumatised and galvanised by political and industrial revolution, her deliberately non-sectarian approach to education, charity, and reform provides a blueprint for a more inclusive and compassionate citizenship. McCracken’s personal magnanimity, and public efforts towards social reform, were motivated by a deep and genuine concern for others rather than any belief in reward. These qualities, and her work towards secularism in a divided region, are worthy of note by humanists today.

Our age, with all its faults, is surely as capable of a sane ideal as any that went before; and […]

Lillie Boileau was a devoted figure within the Ethical movement, and an active part of the fight for women’s suffrage. […]

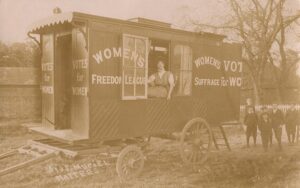

Dare to be free. Slogan of the Women’s Freedom League The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was a militant suffrage organisation, […]

Founded in 1905 by the prolific but largely unremembered writer Richard Dimsdale Stocker, the Brighton and Hove Ethical Society – […]