Why are these minds left without the means of obtaining that knowledge which they so ardently desire and why are the avenues of science barred against them because they are poor?

George Birkbeck

The Mechanics’ Institute movement was a product of the late 18th century, conceived as a means of offering education to working people. By the second half of the next century, there were well over a thousand of these institutions in Britain, providing a mixture of education, entertainment, and social facilities. It was following a lecture at the Cheltenham Mechanics’ Institute in 1842 that George Jacob Holyoake was arrested on charges of blasphemous libel.

To be free, we should be in a position to dare the judgement of the wise.

George Jacob Holyoake, Practical Grammar (1844)

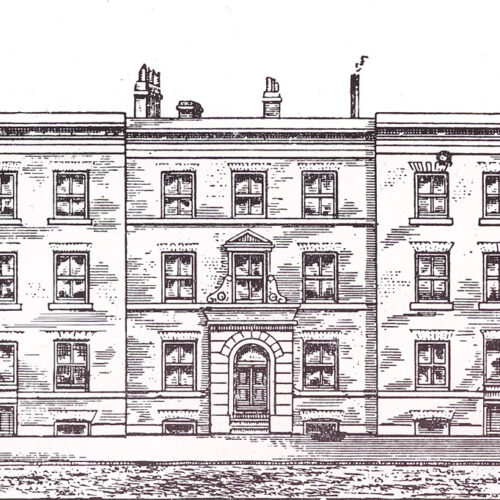

The Mechanics’ Institutes had their origins in the efforts of Glasgow’s John Anderson, who founded Anderson’s Institution in 1795 to be a ‘university open to all’. Today, it is the University of Strathclyde. An earlier lecturer with the Institution was George Birkbeck, who – perceiving a fervent interest in scientific and technical demonstrations among workers – in 1799 introduced classes for tradesmen and mechanics. The scheme proved popular, and Birkbeck would go on to found, in 1823, the London Mechanics’ Institute (now Birkbeck, University of London).

Also in 1823, breakaways from Anderson’s Institution founded the Glasgow Mechanics’ Institute. The decade saw an ever-increasing number of similar organisations established around the UK, some of which were formed by groups of artisans frustrated by their exclusion from other bodies, such as Literary and Philosophical Institutions.

There was significant crossover between the Mechanics’ Institutes and other aspects of radicalism and reform. Significantly for humanist heritage, these included the secularist and socialist movements, members of which both lectured for and attended the institutions. As Edward Royle has written:

The London Mechanics’ Institute was used in the I820s by the Owenites, Huntites, Cobbettites and the followers of Carlile and Taylor. The Chartists controlled the institute at Cheltenham in I842, where the writings of Bentham, Owen and Cobbett were allowed in the library. At Sunderland, two members of the institute were local Chartist leaders. W.J. Birch and Emma Martin, familiar figures in the Owenite Halls of Science, appeared as lecturers in the Manchester District of Mechanics’ Institutions in I840. There is a close connexion between the fortunes of the Socialist and mechanics’ institute movements.

In 1842, following a lecture at Cheltenham Mechanics’ Institute, Owenite speaker George Jacob Holyoake responded to a question from the audience with the suggestion that the deity should be put on half-pay. He was subsequently arrested on charges of blasphemous libel, and the incident widely reported. The example of Holyoake demonstrates, as Royle confirms with others, the space enabled by the Mechanics’ Institutes for freethinking, and the promotion of radical and disruptive ideals, including secularist principles.

The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery primarily located in London but with various satellite outstations located elsewhere in […]

The Humanist Broadcasting Council was established in 1959, in consultation with the BBC, to advocate for the inclusion of humanist […]

Founded in 1263, Balliol College is one of the oldest colleges at the University of Oxford. Established by the English […]

In the first place, then, why do we botanise?… The enjoyment of the beauty and fascination of flowers in their natural […]