I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me.

Michael Manley quoted by Rachel Manley in Slipstream: a daughter remembers (2001)

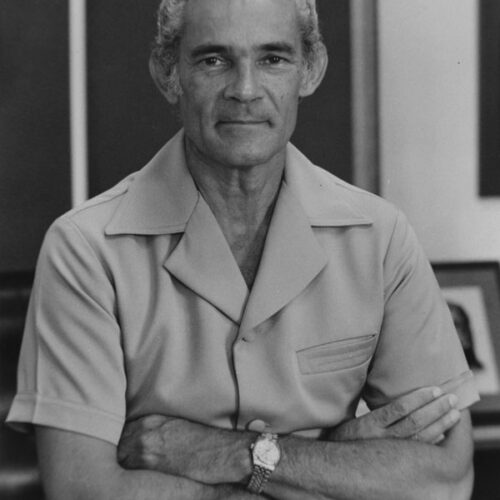

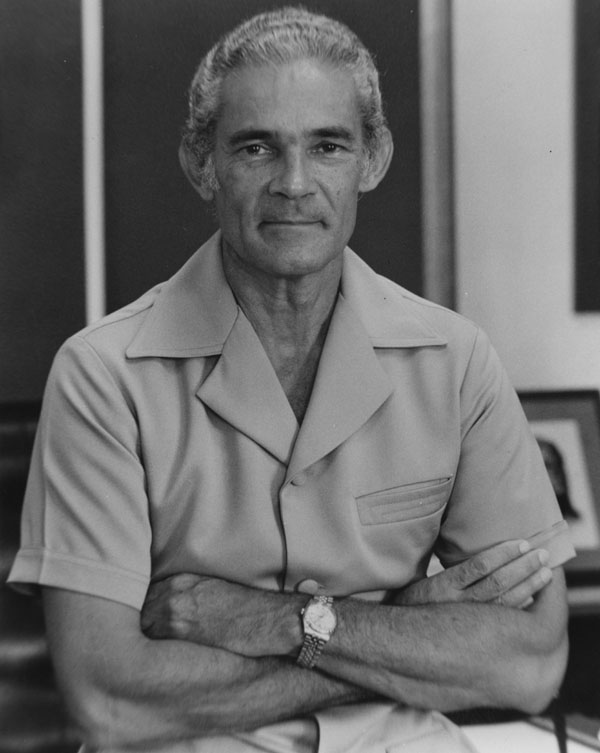

Michael Manley was a politician and activist, who served three terms as the Prime Minister of Jamaica, and is remembered as one of the country’s most popular. An agnostic in matters of religion, Manley was motivated by humanist principles of equality, community, and social responsibility, becoming a charismatic leader and a well-known advocate for developing nations.

Michael Manley was born in Kingston, Jamaica on 10 December 1924, the son of sculptor Edna Swithenbank, and former Prime Minister and co-founder of the People’s National Party Norman Manley. Writing about her father’s background, Michael’s daughter Rachel Manley would later note:

We were not a religious family, despite the fact that Jamaica is a predominantly Christian country and that my grandmother’s father was a Methodist minister once sent to Jamaica from England. I suppose my grandparents were of an age whose intellectuals questioned existing assumptions. Although my grandfather quoted the Bible, and my grandmother wrestled with its themes in her art… their belief systems were not formally inspired by religion.

Educated first in Jamaica, Manley briefly attended McGill University, Montreal, before enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942. After the war, he attended the London School of Economics, where he was inspired by the humanist and socialist Harold Laski. In Cornwall, in 1946, he married for the first time. With Jacqueline Kamellard, Manley had a daughter, Rachel, but the couple divorced in 1951. That year, he returned to Jamaica, and having worked in London as a freelance journalist, he now joined the staff of Public Opinion, a leftist weekly newspaper which supported his father’s political party.

A student organiser while at LSE, back home in Jamaica Manley became active in the trade union movement, ascending to the position of principal sugar organiser for the National Workers Union. He was recognised as a strong leader and deft negotiator, who overcame an aversion to public speaking and became a powerful orator. In 1962, he was appointed to Jamaica’s Senate, and five years later was elected to the House of Representatives as MP for Central Kingston. In 1969, he succeeded his father as leader of the social democratic People’s National Party, becoming Prime Minister on their election win in 1972.

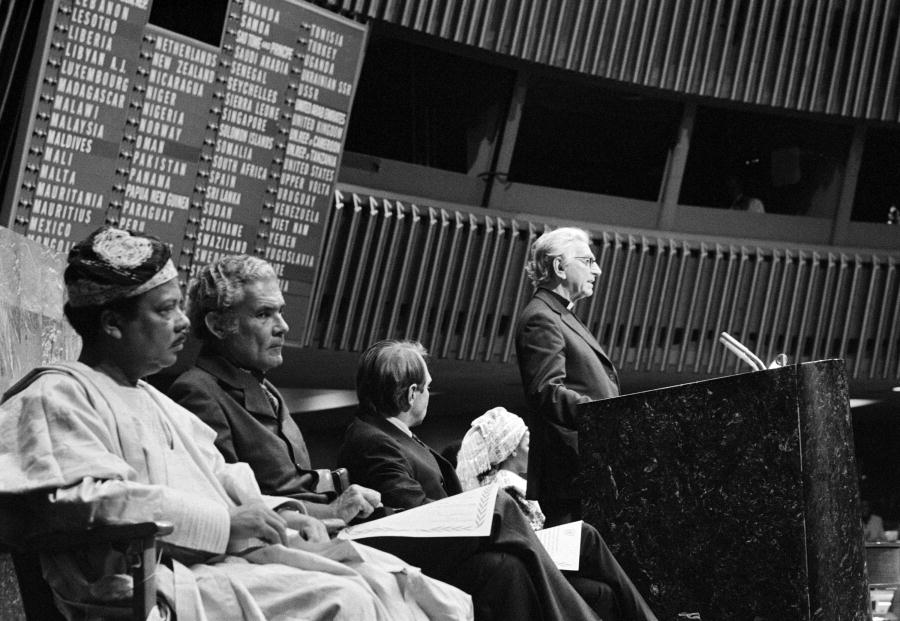

As Prime Minister, Manley was an advocate of Caribbean cooperation, African liberation, and women’s rights, and a staunch critic of capitalism, colonialism, authoritarianism, and apartheid. He set about trying to revitalise Jamaica’s economy, expanding public works, introducing a free education system, and establishing training schemes for the unemployed. The economy, though, continued to decline, and though elected for a second term in 1976, the People’s National Party was defeated in 1980.

Throughout his time in office, Manley had called for peace in Jamaica – among its citizens and between its politicians. One notable example was when Manley’s friend, Bob Marley, invited him and the opposition leader on stage at a ‘One Love’ concert to shake hands and dance. Between 1980 and his re-election as Prime Minister in 1989, Manley continued to write and speak widely in defence of his principles, earning an international reputation.

In a memoir of her father published in 2001, Rachel Manley described a number of instances in which his ideas about religion were revealed. She wrote that, though ‘not a religious man’, he ‘regarded the Bible as grand literature, with riveting stories’. She added that Manley ‘often plundered it for its symbolism, and borrowed its characters’ names to give his children.’ Rachel Manley also recalled a conversation between her father and a Catholic acquaintance, who asked if he believed in God. She recalls her father responding:

That’s like asking me if I believe in the universe… The universe exists and I am connected to it… If you mean, do I believe in a specific religion, or believe that there is a heaven and a hell, that I don’t know. So I must be an agnostic. I suppose I’m an activist, really. I believe in connection.

This central belief in human connection, not any notion of supernatural reward or punishment, animated a lifetime of activism.

In 1991, Manley was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and the following year he resigned as Prime Minister. That year he married his fifth wife, Glynne Ewart, with whom he spent happy final years. Manley died at home in Kingston on 6 March 1997. Rachel Manley later wrote: ‘During the last six months of his illness, when my father was confined to his bed, there had never been talk of a priest.’ In fact, he had commented on the hubris of inventing an afterlife:

I suppose I fear dying, as we all do. But isn’t it just like man to believe he has a right to conjure up more for himself? Not for any other creature, mark you, just for himself, alone in the universe? He invents eternity so that his own mortality may not be in vain! I think it’s a piece of cheek on the part of man to believe there is more than this — more than this one stab at it all. I think, if we were meant to know everything, nature would have given us the imagination and the brains to figure it all out. Let there be mystery, I say!

“So you think that when you die, there will be nothing?” asked this visitor, mildly affronted.

“No. Not at all. There will still be everything… but me! The universe won’t end, but I will! My connection to it will be severed.”

Michael Manley quoted by Rachel Manley in Slipstream: a daughter remembers (2001)

Michael Manley was a humanist of international significance, whose activism in the UK and his native Jamaica was motivated by humanity, not by any religious ideals. A champion of human rights, peace, and cooperation, Manley never let the acknowledged mysteries of life prevent him from taking action in the world.

Michael Norman Manley | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Rachel Manley, Slipstream: a daughter remembers (2001)

It is impossible that Theology can throw any light upon either morality or jurisprudence. Jeremy Bentham Philosopher and jurist Jeremy […]

Life is a wonderful privilege. It imposes great duties. It demands the fulfilment of great tasks and the realisation of […]

Percy Bysshe Shelley was a major poet of the Romantic period, and remains one of England’s best loved and most […]

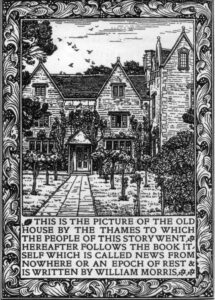

Kelmscott Manor was the country home of the writer, designer, and socialist William Morris from 1871 until his death in […]