A wide-ranging Humanism will always seek to extend to more and more people, through education and opportunity, the enrichment of the personality which music gives… We are morally and emotionally enfeebled if we live our lives without artistic nourishment. Our sense of life is diminished.

Michael Tippett, ‘Towards the Condition of Music’ in The Humanist Frame (1961)

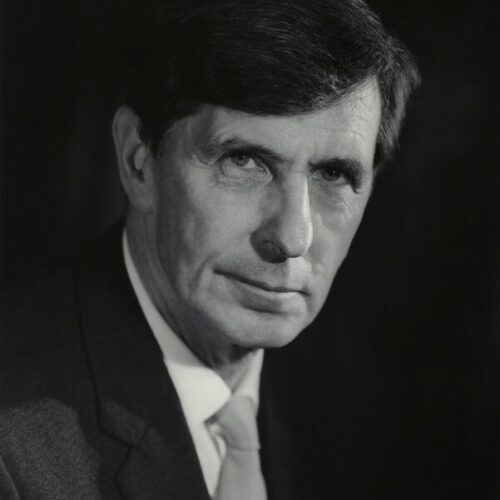

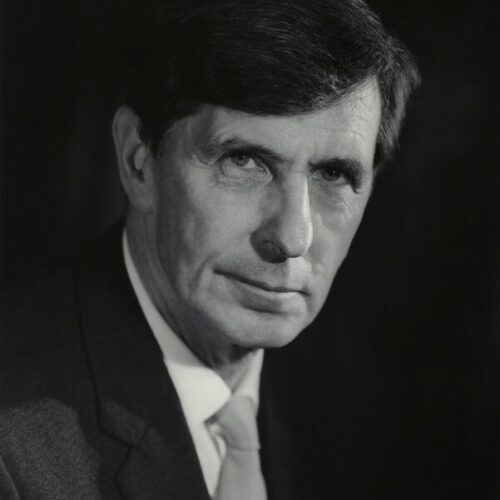

As a young schoolboy, Michael Tippett wrote an essay denying God’s existence. It was an early example of the independent and challenging thinker he would become, but this denial of a god was only part of what would be his lifelong humanism. One of the 20th century’s great British composers, Tippett throughout his long life was deeply and directly engaged with his time. Troubled by the world and the events around him, he turned to music to provide his answers. In his works we find an authentic testimony of what it is to be alive: a commentary on our human condition. Not only that, but in an age riven by two world wars, Tippett strove to offer his fellow man a sense of beauty, solace, joy, and hope.

I know that my true function within a society which embraces all of us, is to continue an age-old tradition, fundamental to our civilization, which goes back to pre-history and will go forward into the unknown future. This tradition is to create images from the depths of the imagination and to give them form whether visual, intellectual or musical.

Michael Tippett, Moving into Aquarius (1959)

Although Michael Tippett was born in London, he grew up in the Suffolk countryside. The second son of a lawyer and a novel writing suffragette, the young Tippett enjoyed no formal musical education apart from singing in the local village church choir. This environment however, together with the experience at age fourteen of hearing a symphonic concert, proved so stimulating for Tippett that he then decided to become a composer. Four years later, as a self-professed greenhorn, he enrolled at the Royal College of Music in London, from which he graduated in 1928.

After his sheltered student life in London, on travelling the country Tippett was confronted with the abject poverty suffered by many during the Depression. Profoundly shaken by what he had seen, Tippett became socially and politically active. He participated in Yorkshire work camps, where he provided musical activities and education for unemployed miners. Back in London, he started teaching at Morley College, a centre for adult education, where he conducted the South London Orchestra made up by unemployed professionals. In 1935, Tippett briefly joined the Communist Party, but left only months later after failing to win others round to his own Trotskyism. Another reason for his departure was his decision to commit himself more devotedly to composition. All of his works up to this period would later be withdrawn by Tippett, bar his revised first string quartet and first piano sonata. His first compositional success was the Concerto for Double String Orchestra, premiered in 1940.

As the war forced Morley College’s then musical director to leave London, Tippett took up the position. Meanwhile, he had begun working on his international breakthrough, the oratorio A Child of Our Time. Written in reaction to the Nazi persecution of Jews, he used the events surrounding Kristallnacht as his inspiration. Composer and biographer of Tippett Meirion Bowen described this as ‘a moving assertion of humanitarianism in an epoch of catastrophe’. Dealing with human suffering and finding light in the darkness, Tippett went back to Bach and his passions for a musical model. While the latter had used Lutheran hymns as a guiding thread, Tippett chose to use African American spirituals, seeing in them a contemporary equivalent. His first opera, The Midsummer Marriage, was started in 1946, and through a tale of lovers deals with the reconciliation of the spiritual and the sensual. With no commission and taking six years to write, this piece is, both in its effort and result, a testament to Tippett’s daring and originality. The opera is seen as his artistic breakthrough.

In the following decades, Tippett would go on to write four more operas (King Priam, The Knot Garden, The Ice Break, and New Year). In these works, Tippett expressed his take on the world around him. Ranging from the human psyche, to racial tensions, and the bomb on Hiroshima, his operas illustrate the composer dealing with humanity’s tragic condition as seen in the events of the 20th century. Although less obvious due to the absence of words, the same struggle can be detected in many of his instrumental works. In his Symphony No. 3, Tippett quotes and distorts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (the text of which was adapted from Ode to Joy). Though a great admirer of Beethoven, the events of the 20th century had shattered a utopian belief in human brotherhood. Instead, Tippett offered an admission of our potential to do both good and evil: a realisation on which a more nuanced optimism could be built.

Tippett’s humanism was intertwined with his art and his activism. A lifelong pacifist and a conscientious objector during the war, Tippett spent two months in prison for civil disobedience in 1943. He later became President of the Peace Pledge Union, and was a supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In 1994, he unveiled the Conscientious Objectors’ Commemorative Stone in London’s Tavistock Square. In Moving into Aquarius—a collection of essays and poems—Tippett quoted words he’d spoken at a pacifist gathering the year of his imprisonment as a CO, and highlighted the importance of a ‘joyful humanism’ in remaking a post-war world. He said:

When I was in prison I was struck most of all by the gaiety and vitality of the group of young comrades there. It was as though having made the fact of their moral integrity clear by the submission to imprisonment they were yet able to turn to the community around them and to live in generous contact with its members. I feel this has a meaning for all of us. Unless there is room in our movement not only for the necessary moral attitude, but also for the exuberance and everrenewing spring of life, then it has nothing to contribute to the society that is to come after the war. We need to temper the ‘prophetic gloom’ into which we are apt to descend, with a proper and joyful humanism.

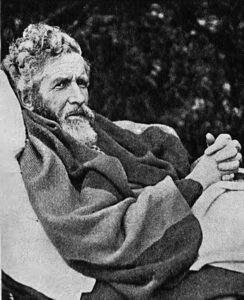

In 1982, Tippett’s The Mask of Time was first performed in Boston, Massachusetts. This evening-long work commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra had been partly inspired by fellow humanist Jacob Bronowski‘s television series The Ascent of Man. As Geraint Lewis wrote for Tippett’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ‘this hugely ambitious work evolves from myths of creation to the presentation of man’s place in history with a breathtaking sweep of invention’. From a climactic elegy for victims of war, Lewis wrote, ‘Tippett presents an exhilarating concluding vision of hope in the future, thus setting a seal on a vivid and idiosyncratic summation of the concerns of a lifetime’.

Michael Tippett died in January 1998, at the age of 93, and was cremated with a non-religious service.

His humanism has a personal basis. The traumas of his childhood and youth loom large. But he can step outside them and relate to world issues on their own terms. He is aware that individuals need to live out their lives to the full.

Meirion Bowen in Michael Tippett (1982)

As a composer, Tippett felt compelled to engage with the world. Although he brought us music of exceeding beauty, aesthetics alone did not cut it for him. Struggling with the world around him and creating music as a way forward, Tippet made works for his fellow human beings. Where there was darkness, he tried to bring light. His humanist efforts also went beyond his art, guiding his firmly felt pacifism and lifelong sense of social responsibility.

Sir Michael Tippett by Geraint Lewis | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Michael Tippett by Oliver Soden | The Michael Tippett Musical Foundation

Michael Tippett | Men Who Said No

David Clarke, The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett (2001)

By Johannes Bogaert

Not Religion as a Duty, but Duty as a Religion. Felix Adler(A motto of the East London Ethical Society) The […]

Hath man no second life? Pitch this one high! Sits there no judge in Heaven our sin to see? More […]

[I] feel extraordinarily proud and extraordinarily lucky to be the child of a woman who from her early twenties was […]

It has been suggested that matter is capable of destruction, that every atom is destined to be dissolved away in […]