It is not because the believer in rational religion has not clear convictions that he will not shape them into a creed. It is because the experience of the world has proved that however well a creed may express the thought of one generation it is very certain to impede the thought of another.

Our Cause and Its Accusers: a Discourse Given at the Athenaeum, Camden Road, June 11 1876

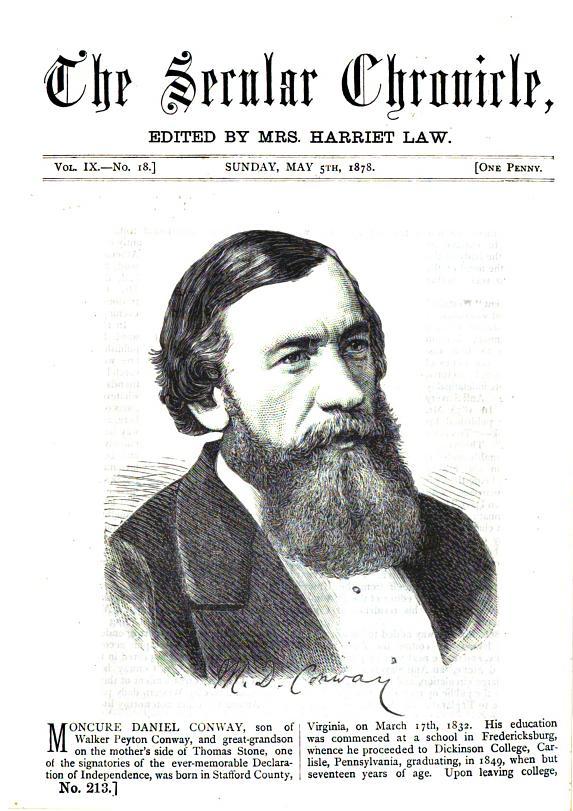

Moncure Conway was born the son of Virginia slave-owner, and became an outspoken abolitionist and defender of freedom. Starting out as a Methodist preacher, Conway moved into Unitarianism, taking over the ministry of South Place Chapel in 1863, which he led with great success for over two decades. Conway lived, wrote, and spoke by the belief that ‘those who think at all think freely’, and was arguably himself a humanist by the end of his life. His efforts to secure Stanton Coit as his successor at South Place, officially renamed it an ethical society, enabling its final evolution into a humanist organisation. In recognition, Conway Hall was named for him.

Moncure Conway was born on 17 March 1832 at Middleton Plantation, Stafford County, Virginia. His parents were pious methodists: his father a planter, attorney, judge, and slave owner. His upbringing was coloured by the diverse influences of his socially prominent male relations, and the cultural and abolitionist tendencies of his mother and female relatives.

Conway obtained his BA from Dickinson College, Pennsylvania, after which he briefly studied law before inclining toward the Methodist ministry, which he entered aged 19. Objecting to what he believed was a suppression of free thought, he attended Harvard Divinity School in 1853 to train for the Unitarian ministry.

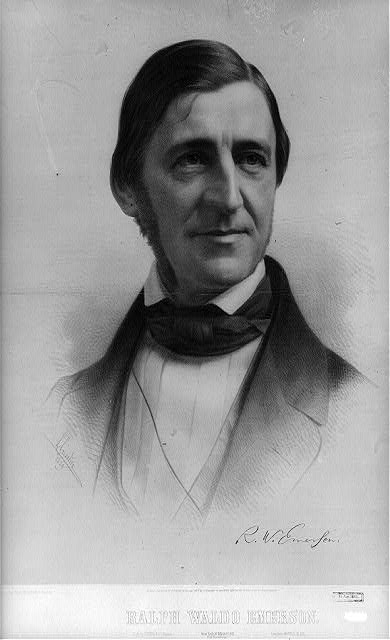

His time in Massachusetts marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship with Ralph Waldo Emerson, and a public expression of his anti-slavery sentiment. At a rally for the cause on 4 July 1854, he declared himself an abolitionist. In the same year, he received his degree and took the Unitarian pulpit in Washington DC. Conway was dismissed from here in October 1856 for preaching anti-slavery sermons, hired instead (and immediately) by a congregation in Cincinatti, Ohio. Here, in 1858, he married Cincinnati-born Ellen Dana (1833-1897).

The American Civil War (1861-1865) saw his father remain in the south, his two brothers in the Confederate Army, and his mother and sister (pro-Union) in the north. In 1861 and 1862, Conway wrote two anti-slavery books, The Rejected Stone and The Golden Hour, as well as co-editing anti-slavery newspaper The Commonwealth. Slavery, ‘this wild disease of the South’, he challenged in word and deed: in 1862, with his wife, Conway led his family’s 31 slaves from Virginia to Ohio by train. A community established by two of this group, Dunmore and Eliza Gwinn, was named Conway Colony.

In April 1863, Conway finally left the USA, embarking on an anti-slavery speaking tour in England. His first lecture was at South Place Chapel, on 6 May. In August of that year, he was hired as its minister. Of this, John d’Entremont writes:

It was a perfect match: the congregation applauded Conway’s intellectual boldness, encouraging his attacks on sabbatarianism, sexual prudery, blasphemy laws, patriarchy, monarchy, and other apparent restraints on liberty, conscience, and expression.

In spite of this unabashed forthrightness, Conway was clearly a personable and beloved man as well as preacher. ‘Let gentleness your true enforcement be,’ might have been written for him’, recalled congregation member Caroline Fletcher-Smith in May 1921.

Over the following years, Conway replaced pews with normal seats and dropped the title of minister. He referred to ‘discourses’ rather than sermons and substituted prayers for devotional readings, or ‘meditations’. The Committee continued to support Conway through these progressive changes, agreeing that ‘the service would gain rather than lose in warmth, earnestness, and devotion’ in following his suggestions. Conway’s Sacred Anthology, from which he read beginning in 1873, was published in the belief that:

… it would be useful for moral and religious culture if the sympathy of Religions could be more generally made known, and the converging testimonies of ages and races to great principles more widely appreciated.

In this collection, Conway aimed ‘to separate the more universal and enduring treasures contained in ancient scriptures, from the rust of superstition and the dross of ritual’. The presence of texts from Confucianism, Hinduism, and Buddhism testifies to the influence of Eastern religion on Conway’s own belief and philosophical eclecticism.

He was a passionate supporter of the women’s suffrage movement, and spoke alongside Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, and Robert Browning at the first open public meeting in support of women getting the vote, in 1868. In 1878, Conway attempted to personally endow what would have been the first women’s college at Oxford. Historian Dr Laura Schwartz writes that the religious establishment, already concerned that University College London was leading ‘respectable women’ away from religion, made haste instead to establish their own such college, Lady Margaret Hall, instead.

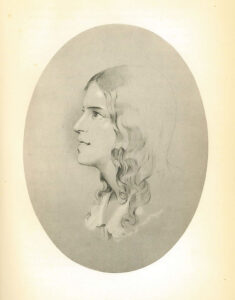

Conway was a prolific writer, contributing articles to British and American periodicals on a diverse range of subjects. He also acted as the English agent for a number of notable American authors, including Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Louisa May Alcott. Conway’s artistic predilections extended too to theatre and art, and he enjoyed close friendships with many key Pre-Raphaelites. One of these, Arthur Hughes (1832-1915), painted Ellen Dana Conway’s portrait in 1873 (now in Conway Hall).

In 1885 Conway returned to America with his family, settling in New York. Over the following years, he continued writing, including his two volume biography of Thomas Paine (1892) and an edited collection of Paine’s writings in four volumes.

In 1893, following the departure of Stanton Coit, Conway resumed leadership of South Place, remaining there until 1897.

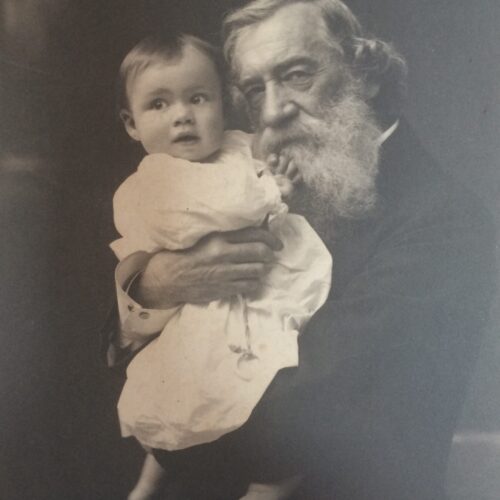

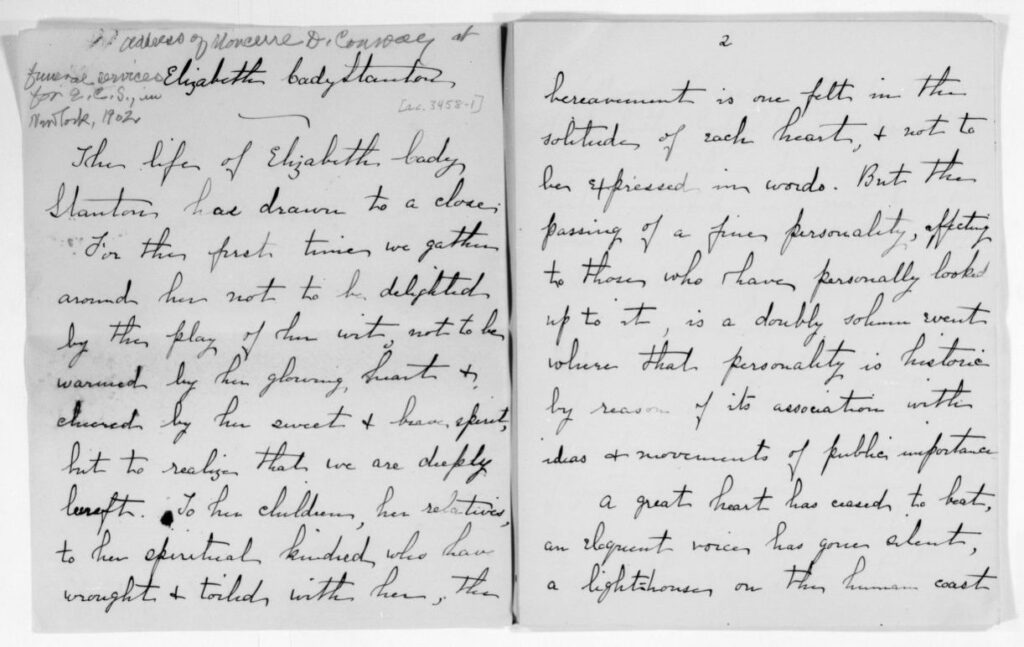

Conway gave the eulogy at the funeral for his fellow feminist and friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1902. ‘A great heart has ceased to beat, an eloquent voice has gone silent, a lighthouse on the human coast is fallen.’ He himself died in Paris on 15 November 1907, his cremation overseen by fellow expat Edward Steichen.

Strike out the word white and the word male from our laws, and we shall reach the noblest transformation.

The Commonwealth, 1865

Borne out by the hall that bears his name, Moncure Conway was a central figure in the development of South Place through rational religion towards an ever increasing humanism. It was Conway who, in his unwavering defence of progressive freethought and strong support of his South Place successor Stanton Coit, enabled its renaming as an ‘Ethical’ Society. As a devoted abolitionist, feminist, and thinker, Conway’s legacy is one of compassion, principle, and lifelong service to humanity.

‘This is our cause. We have no fear for it. We love it, for it means to us reverence for all that is sweet in the past and pure in the present; we have faith in it, for it means to us pursuit of truth and fidelity to it; we rejoice in it, for in it we see germinating the freedom and fraternity of man, and in it all the great hopes of humanity climbing to fulfilment.’

‘Our Cause and Its Accusers’, 1876

Lillie Boileau was a devoted figure within the Ethical movement, and an active part of the fight for women’s suffrage. […]

Humanists International was formed in 1952 as the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU): a federation of the American Ethical […]

If the basic cause of an unsuccessful marriage is removable, conciliation is the proper procedure. If it is not removable, […]

Eliza Flower was a composer, a radical, and a significant influence on William Johnson Fox and the progressive values of […]