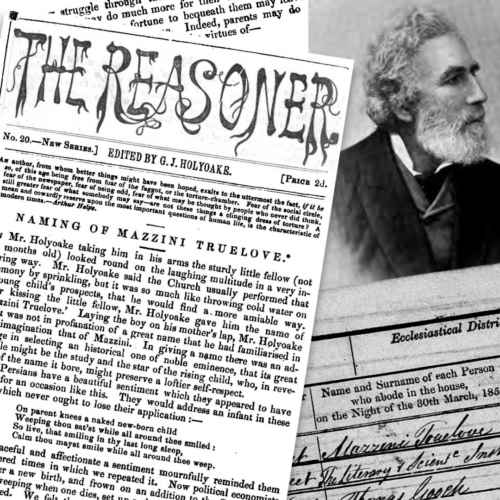

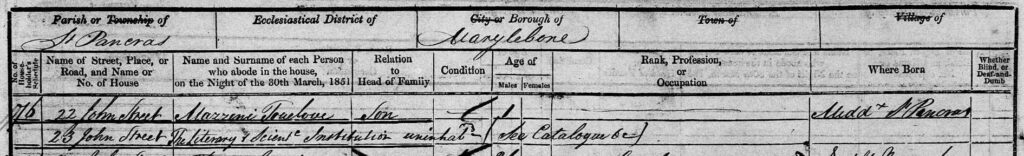

On 11 November 1849, at the Literary and Scientific Institution, 23 John Street (now Whitfield Street), London, George Jacob Holyoake led a secular naming ceremony for Mazzini Truelove, the son of radical publisher Edward Truelove. Conducted in the Owenite tradition, the ceremony marked the naming of the infant Truelove after Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini, and called upon the community to help raise him with values of honesty, kindness, and freedom of thought. In tailoring a ceremony to reflect the beliefs and values of the people involved, this was a precursor to today’s humanist naming ceremonies.

At the Literary Institution, John Street, on Sunday, November 11, 1849.

ON Mr. Holyoake taking him in his arms the sturdy little fellow (not six months old) looked round on the laughing multitude in a very inquiring way. Mr. Holyoake said the Church usually performed that ceremony by sprinkling, but it was so much like throwing cold water on a young child’s prospects, that he would find a more amiable way. After kissing the little fellow, Mr. Holyoake gave him the name of ‘Mazzini Truelove.’ Laying the boy on his mother’s lap, Mr. Holyoake said it was not in profanation of a great name that he had familiarised in their imagination that of Mazzini. In giving a name there was an advantage in selecting an historical one of noble eminence, that its great example might be the study and the star of the rising child, who, in reverence of the name it bore, might preserve a loftier self-respect.

In giving a name there was an advantage in selecting an historical one of noble eminence, that its great example might be the study and the star of the rising child

The Persians have a beautiful sentiment which they appeared to have framed for an occasion like this. They would address an infant in these terms, which never ought to lose their application:–

On parent knees a naked new-born child

Weeping thou sat’st while all around thee smiled:

So live, that smiling in thy last long sleep,

Calm thou mayst smile while all around thee weep.

We are admonished by these reflections to connect with this occasion some suggestions to the guardians of our little friend, which may influence his training and fit him for the long struggle through the wilderness of life.

But so graceful and affectionate a sentiment mournfully reminded them of the altered times in which we repeated it. Now political economists preside over a new birth, and frown on an addition to the Census; and instead of weeping when one dies, set up a shout that the Labour Market is so far freed. We felt that we were in a state of society in which the purest and warmest affections were chilled. They could see from this point how much the system of Mr. Owen was maligned by being represented as hostile to human nature. In seeking to provide a place at Nature’s table for all her children, it restores affection to childhood and regret to the bedside of the dying. We are admonished by these reflections to connect with this occasion some suggestions to the guardians of our little friend, which may influence his training and fit him for the long struggle through the wilderness of life. The humblest parents in this Hall may do much more for their children than is commonly done. They who have no fortune to bequeath them may leave them the inheritance of an unsullied name. Indeed, parents may do more—they may illustrate before their children the virtues of:—

1. Straightforwardness of speech.

2. Silence or truth.

3. An iron will.

4. Independent ideas.

5. Self-respect.

6. Self-dependence.

7. Obedience to reason.

8. Conquest by kindness.

9. A perseverance which never pauses, and an endurance which never fails.

Cultivate ‘independence of ideas’—let notions be new from nature, not worn and second-hand. Let there be a ‘self-respect’ that never stoops to meanness

The senses of a young child, like the daguerreotype, receive at once, and often retain for ever, the images of speech and act by which he is surrounded at his own fireside. There strict example may mould the habits of children. There they may learn simplicity and purity of thought, and purpose in speech, and the resolution to maintain ‘silence or tell the truth’—a resolution which is a wonderful source of innocence and intellectual strength. Let there be added to the wisdom of few aims an untamed spirit that never blenches, when in the right, before the threat of foe or the power of opinion. Cultivate ‘independence of ideas’—let notions be new from nature, not worn and second-hand. Let there be a ‘self-respect’ that never stoops to meanness—a ‘self-dependence’ which can stand alone even in desolation—and that unbending purpose may never issue in antagonism, inculcate instant ‘obedience to reason.’ We know not the noble repose, the glowing calm of that life which makes its law of‘ conquest’ the law of ‘ kindness.’ Love puts us on the sunny summits of life, where we live above the dark passions that bind humanity to slavery and darkness below. That man has no fee who is the foe of no man. Neither fear nor death are present to him who acts only to bless others. Lastly, let there be connected with the associations of this child whom we have named, the majestic maxim of him whose great name he hears. Like Mazzini, let him hold that indolence is the death of the soul, that the secret of progress is labour—and in his endeavours after the improvement of others, let him possess that ‘perseverance which never pauses, and that endurance which never fails’. It is not enough that we work—we must learn to wait for the fruits of our working. All men will stand on our side when they see as we see. The part of wisdom is to labour untiringly to show men the good, and to endure the evil till they see the good.

It is not in conformity with my ideas of usefulness to invoke, as the Church would do at the conclusion of this ceremony, your benediction upon this child. But let me remind you that there is a grander benediction than prayer in your power to pronounce.

It is not in conformity with my ideas of usefulness to invoke, as the Church would do at the conclusion of this ceremony, your benediction upon this child. But let me remind you that there is a grander benediction than prayer in your power to pronounce. If you gather up the words spoken to-night, and realise them in your practice—if you can work with heroic devotion for the improvement of others in the spirit of that system which has been explained–justice, and truth, and love will spring up in your walks of life, where strife, and passion, and discord have heretofore existed; and thus you will smooth the way of this young child through the world, and bedeck his path with flowers, and pronounce a living benediction upon him, which will also be a benediction upon yourselves.

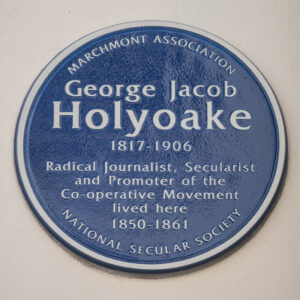

On Woburn Walk is a plaque to George Jacob Holyoake (1817-1906), a writer, lecturer, and promoter of the Cooperative movement, […]

Kelmscott Manor was the country home of the writer, designer, and socialist William Morris from 1871 until his death in […]

From the Agnostic Annual, 1900, edited by Charles A. Watts (founder of the Rationalist Press Association). THE RATIONALIST PRESS ASSOCIATION, […]

As well as being one of the most distinguished musicians of his time, he was, like Sir Hubert Parry before […]