…no child should be made ashamed or uncomfortable on account of his father’s opinions, or lack of opinions, on subjects of theological speculation; no child should imbibe lessons of sectarian hatred, or be encouraged to think himself better than another child, because he had been taught something different about creed or catechism.

Henry J. Slack, Denominational schools: their principle examined (1869)

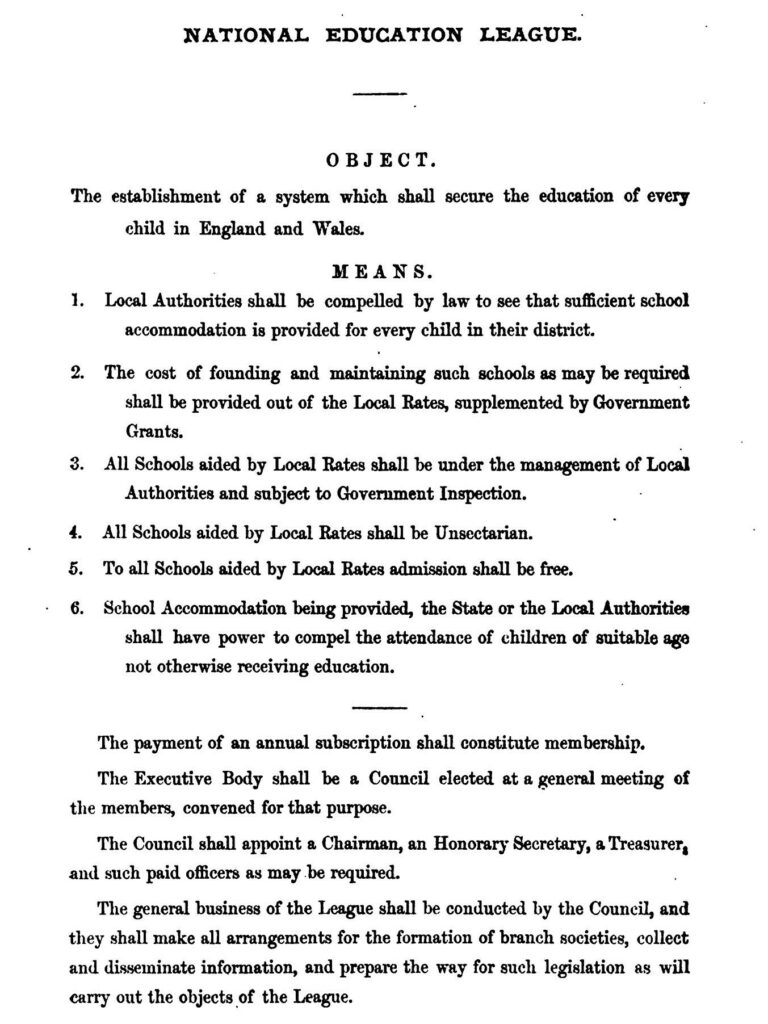

The National Education League was founded in Birmingham in 1869 to campaign for free, compulsory, non-sectarian education for all children in England and Wales. The main result of the League’s activities was the passing of the Elementary Education Act 1870 which met some, but not all, of the League’s objectives. Present at the League’s first conference (and a member of its Council) was George Jacob Holyoake, who put forward an ideal of practical, secular education for all.

The founding conference of the League was attended by 44 MPs and many leading progressive campaigners. They heard that according to government data about two million children between the ages of five and thirteen (46% of the total) were getting no education at all, and many of those present knew from personal experience that around half of the adults in Birmingham and Manchester were unable to read. Of those children who were in school, about three-quarters were being educated by either the Church of England or the Catholic Church, and the remainder were in schools run by various non-conformist churches. But the government’s Inspector of Schools was convinced there was no possibility that the churches would provide the additional school places which were badly needed, particularly in the large towns. The conference therefore concluded that the only solution was to compel local authorities to provide publicly-funded primary school places in newly-built schools and to make school attendance compulsory. This meant that the new schools would have to be non-sectarian.

Among those attending the conference was George Jacob Holyoake, who read a paper entitled ‘Misconceptions as to Secular Instruction’. Holyoake argued that when the state was funding education, that education should be both practical and secular. In his view the state:

…is bound to expend the public money in productive knowledge, and the only knowledge which is productive is secular; and this knowledge the State is bound in prudence and justice to give to the people.

Holyoake was very much in tune with the general feeling of those present. Other speakers insisted that any system of compulsory state-funded education must be non-denominational. It would clearly be wrong to compel parents to send their children to a school whose doctrine they objected to, or ask rate-payers to fund such a school when they had conscientious objections to doing so. And concern was also expressed about the effects which religious education had on children. As one participant put it, school places should be allocated solely on the basis of merit:

…no child should be made ashamed or uncomfortable on account of his father’s opinions, or lack of opinions, on subjects of theological speculation; no child should imbibe lessons of sectarian hatred, or be encouraged to think himself better than another child, because he had been taught something different about creed or catechism.

The conference therefore resolved that the proposed new publicly-funded schools should be prohibited from teaching ‘catechism, creeds, or theological tenets peculiar to sects’. But school managers should be allowed to give children readings from the Bible, provided these were given ‘without note or comment’.

In the event the Elementary Education Act 1870 was a compromise which met only some of the League’s aims. It gave local authorities the power to create new publicly-funded primary schools to be directed by elected School Boards, and over the next ten years some 3,000 to 4,000 ‘Board’ schools were created. Not all local authorities made attendance compulsory; most parents had to pay school fees and the Boards were empowered to make grants to existing church schools. However, the Board schools were non-denominational, with religious teaching being limited to learning the Bible and a few hymns, and parents were given the right to withdraw their children from any religious instruction that was provided. In fact, the Act allowed Boards to provide no religious instruction at all in their schools if that was what they preferred. A further significant benefit was that the Board schools provided new opportunities for women to work as teachers and to hold elected public office as members of School Boards. Many leading members of the ethical societies, including Ruth Homan, Bessie Mabbs, and Hilda Miall-Smith took advantage of this.

The League continued to campaign for its objectives after the passing of the 1870 Act, and in 1880 a new Elementary Education Act made full-time primary education compulsory throughout England and Wales. The League had thus achieved its main aim, though universal free elementary education was not introduced until 1891.

The Age of Reform 1815–1870, Sir Llewellyn Woodward (1962)

The 1870 Education Act | UK Parliament

Education in Britain: 1750-1914, W.B. Stephens (1998)

By Paul Ewans

The Rationalist Press Association (later known as simply the Rationalist Association) had its origins in the London print works of […]

To summarise why I have become a rationalist is a difficult task for one not educated in formal writing, but […]

F.J. Gould was an influential educationist, writer, and humanist, whose tireless work towards secularising education helped to lay the groundwork […]

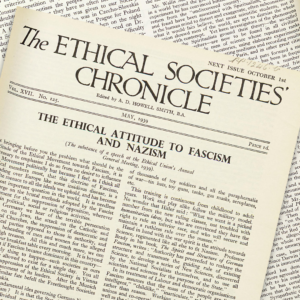

From The Ethical Societies’ Chronicle, Vol. XVII. No. 125. May 1939 The Ethical Attitude to Fascism and Nazism (The substance […]