Humanism involves not just the deletion of God from moral thought, but the development of humanity on a rational and practical basis; this could provide material for many school assemblies and for many thoughts for the days.

Nicolas Walter, ‘Morals exist in a world without God’ (letter to the Independent)

Nicolas Walter was a leading humanist and freethinker, who made significant contributions to the anarchist, peace, and humanist movements. An engaging writer and principled activist, Walter’s career was diverse and his influence widespread. He was a formidable campaigner against the laws governing blasphemy and assisted dying, as well as a veteran activist for peace and nuclear disarmament.

As many thinkers have said – from Epicurus to Spinoza and onwards – we should always think about life rather than death. This is especially true if you think there is no life after death, as I do.

Nicolas Walter, ‘Living Without Religion’ on the BBC World Service, 1996

Nicolas Walter was born into a rich pedigree of freethought: his paternal grandfather Karl Walter had been a prominent anarchist; his maternal grandfather S.K. Ratcliffe a leading humanist; and his father, neuropsychologist W. Grey Walter, a socialist and atheist. After studying history at Exeter College, Oxford, Walter embarked on a lifelong journalistic career, which included stints for Which? (1963-65), the British Standards Institution (1965-67), and the Times Literary Supplement (1968-74). From 1975 until retirement, he was closely involved with the work of the Rationalist Press Association. Walter edited New Humanist magazine 1975–1984, after which he remained a managing director and writer for the RPA. His life as a journalist, and as a prolific writer of letters to the press, was marked by a phenomenal attention to detail, and a fierce devotion to accuracy. He was also a fearlessly original thinker. As Jim Herrick wrote after Walter’s death, ‘he was not the sort of journalist who reboiled others’ bones’.

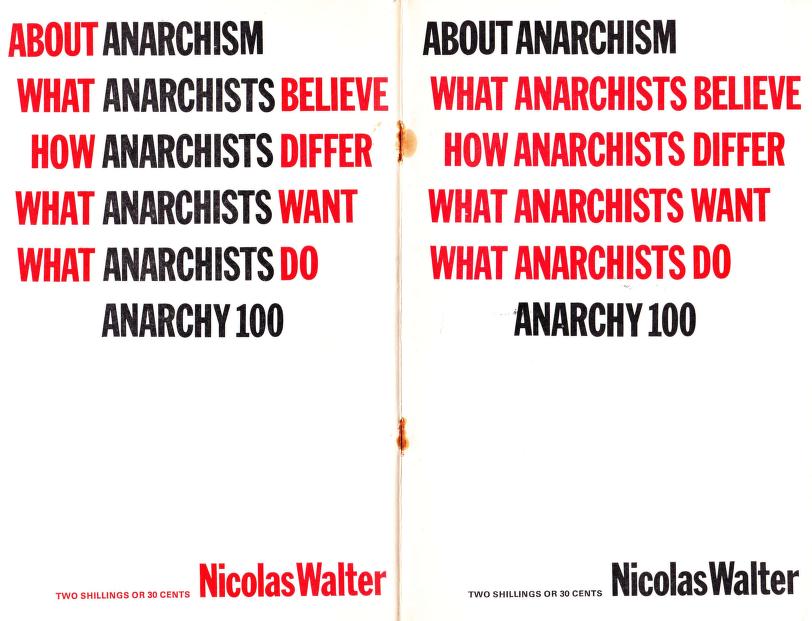

Over the course of his life, Walter took up a remarkable range of causes, all closely linked to his humanism, anarchism, and peace advocacy. One form of activism came in his regular letters to the press: challenging religious bias in broadcasting, theological education in schools, blasphemy laws, and religious charities, and to correct inaccurate reporting on everything from Charles Bradlaugh’s struggle to enter parliament, to the voluntary euthanasia campaign. By his own estimate, more than 2000 of Walter’s letters made it to publication. He also penned influential expressions of his philosophy in the widely translated pamphlet About Anarchism (1969), and Humanism: What’s in the Word (1997). Walter was also the author of Nonviolent Resistance: Men Against War (1963); and Blasphemy Ancient and Modern (1990).

In 1961, Walter (along with his wife Ruth, née Oppenheim) was a founding member of the anti-nuclear Committee of 100, as well as of direct action group Spies for Peace. In 1963, members of the Spies for Peace broke into what turned out to be ‘Regional Seat of Government 6’, one of a number of nuclear bunkers from which a select few would govern the country in the aftermath of nuclear war. The group collated the documents they discovered there, and circulated their findings as the pamphlet Danger! Official Secret. Arguing that those behind these bunkers were ‘quietly waiting for the day the bomb drops’ and planning for military government, the pamphlet had a significant impact on the British public, who were unaware of such preparations, or the perceived gravity of the nuclear threat.

In 1966, Walter received a two month jail sentence for disrupting a church service during the Labour Party conference, accused of (in the words of the Times) ‘riotous behaviour during divine service’. In 1969, he published About Anarchism, giving expression to ideals firmly held:

It is the anarchists, and the anarchists alone, who want to get rid of government in practice. This does not mean that anarchists think all men are naturally good, or identical, or perfectible, or any romantic nonsense of that kind, it means that anarchists think almost all men are sociable, and similar, and capable of living their own lives… Anarchism is an ideal type which demands at the same time total freedom and total equality.

Nicolas Walter, About Anarchism (1969)

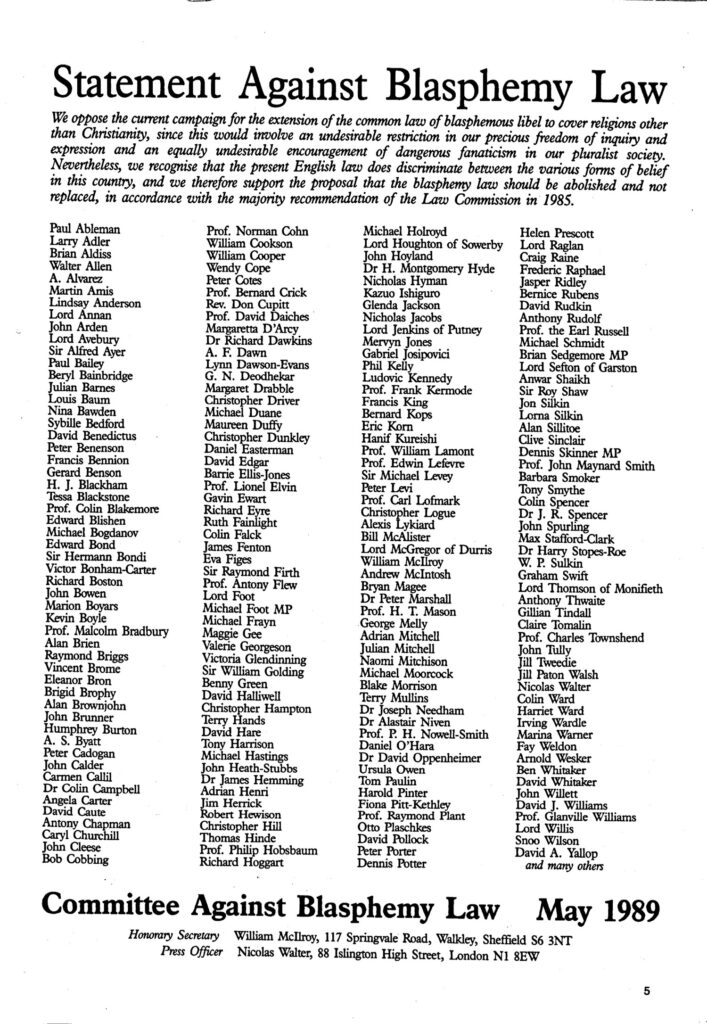

Walter was firmly against censorship, and a fierce opponent of blasphemy laws. With William McIlroy, in the aftermath of the fatwa calling for Salman Rushdie’s assassination, Walter re-formed The Committee Against Blasphemy Law. Their ‘Statement Against Blasphemy Law’ was signed by over 200 public figures. In a letter to the Times in 1989, Walter wrote:

Surely a much better solution would be for everyone to learn to accept the toleration of offence as part of the price that has to be paid for the liberty and equality of all beliefs and groups in the community.

In Blasphemy Ancient and Modern (1990), he quoted a 1912 work by Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, who had written that though persecution ‘has sometimes killed the heretic… it has never killed the heresy’.

Walter was also an active and vocal supporter of the right to die, a position clearly in line with his central beliefs in human agency and liberty. In 1975 he wrote:

In our view the right to live involves the right to die when life ceases to have value; and what used to be called a Roman death may be seen as a rational death for those who wish to make up their own minds.

Nicolas Walter, letter to the Times, 27 February 1975

Walter was diagnosed with cancer in 1973, and later suffered radiation side effects which resulted in progressive paralysis. The stoicism with which he met the illness was widely remarked upon. In a letter to The Guardian, Walter had once written:

Raging against the dying of the light may be good art, but it is bad advice. ‘Why me?’ may be a natural question, but it prompts a natural answer, ‘Why not?’. Religion may promise life everlasting, but we should grow up, and accept that life has an end as welI as a beginning… Mortality is inevitable, but morbidity is not.

Nicolas Walter died on 7 March 2000, remembered by Jim Herrick in the New Humanist as ‘a man of great honesty’, whose ‘desire to improve a manuscript and to improve the world were all of a piece’.

Between these dreams, we are awake, through the will to live, and through love. For what we live in the end by is indeed love.

Nicolas Walter, ‘Living Without Religion’ on the BBC World Service, 1996

In a letter to The Guardian after Walter’s death, Barbara Smoker noted:

Nicolas’s passion was free speech – not least for those whose opinions he opposed – provided only that there was an equal right of reply. Thus, when Gay News and its editor Denis Lemon were convicted of blasphemy (at Mary Whitehouse’s instigation) for publishing James Kirkup’s The Love That Dares To Speak Its Name, Nicolas, while loathing the poem’s religiosity, distributed thousands of copies of it, under the imprint “Free Speech Movement”.

Walter, so large a part now of the humanist tradition, was well aware of the freethinkers that came before. He used this knowledge to reinforce his own convictions before others, and was proud to continue a generations-old family tradition of freethought. After his conviction for disrupting the church service in 1966, Walter wrote:

It isn’t necessarily a bad thing to interrupt a church service, and it may be a good thing sometimes. There are plenty of respectable precedents. The conscientious objectors did it in the first world war, the Suffragettes did it before them, and the London unemployed did it before them. Long before that, the Quakers did it, and long before that, the Men of Kent interrupted mass in Canterbury Cathedral at the beginning of the Peasants’ Revolt. You can’t go much further back than that, and I’m glad to have taken part in reviving such a good old tradition.

Main image: Nicolas Walter. Conway Hall Humanist Library and Archives. Walter was an Appointed Lecturer at Conway Hall 1978–2000

Nicolas Walter by David Goodway in The Ethical Record

Memorial meeting for Nicolas Walter in The Ethical Record

Damned fools in utopia and other writings on anarchism and war resistance by Nicolas Walter, ed. David Goodway

I might fill columns with tales of the debaters, co-operators, socialists, individualists, critics, artists, scientists, clergy and cranks, who, as […]

Dr Alice Vickery was a humanist, physician, and devoted champion of women’s reproductive rights. Her tombstone inscription remembers her as […]

Formed in the wake of the Gay News blasphemy trial, GALHA (now LGBT Humanists) came into being in 1979 as […]

Its main concern is with peace and security and with human welfare, in so far as they can be subserved […]