…life itself offers enough explanation for living; and believing our existence to finish with death, we naturally make the most of our opportunities.

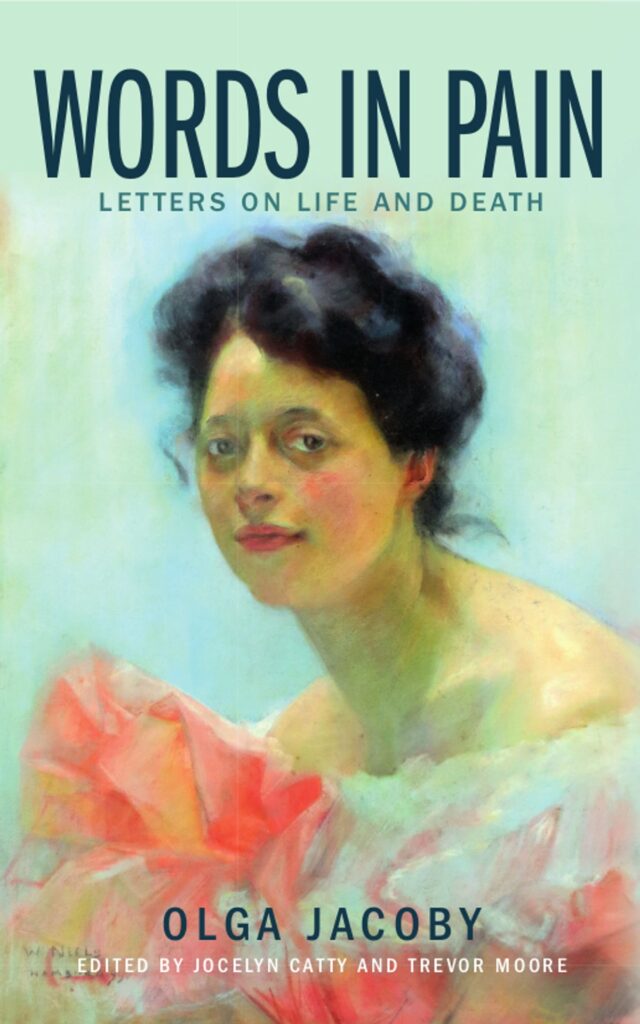

Olga Jacoby

From a life cut short by illness, Olga Jacoby left behind a collection of letters between her doctor and herself which reveal a timeless and deeply humanist attitude to living and dying. In them, she made a case for morality without religious faith, for the pleasures of life and family, and for the right to die with dignity. Jacoby’s letters provide a valuable glimpse into the humanism of the ‘ordinary’ person in Victorian and Edwardian Britain, whose values were shared by a far larger number than is often supposed.

Emanating from her letters is evidence of how Jacoby lived her values — her reverence for beauty, her devotion to generosity — in the minutest details of her life.

Maria Popova, ‘Extraordinary Letters on Love, Life, Death, Courage, and Moral Purpose Without Religion from a Victorian Woman Who Lived and Died with Uncommon Bravery‘ (2019)

Olga Jacoby was born Sara Olga Ilke in Germany on 15 August 1874. She married John Jacoby, a lace manufacturer, settling in Hampstead, London. Together they adopted four children. The letters, so revelatory of Jacoby’s firm, compassionate humanism, were written between 1909-1913 to her religiously devout doctor, from whom she had received a terminal diagnosis. In them, as Maria Popova has written, she:

took up the subject of living and dying without religion, with moral courage, with kindness, with radiant receptivity to beauty, in stunning letters… [which] are symphonies of thought, miniature manifestos for reason and humanism, poetic odes to the glory of living and the dignity of dying in full assent to reality.’

Jacoby’s letters testify to her closeness with her children, to her enduring fascination with life and literature, and to an eloquent faith in science and reason. On discovering her doctor has not read Shelley, she seeks out a copy of his poems as a gift. She discusses matters of politics, and has read the writings of T.H. Huxley. Like Shelley and Huxley, she is confident in her agnosticism, and alert to the influences of science and religion:

Science is turning on the light, but at every step forward dogmatic religion attempts to turn it out, and as it cannot succeed it puts blinkers on its followers, and tries to make them believe that to remove them would be a sin.

Jacoby herself refused all blinkers, and looked squarely at the realities of both life and death. The letters reveal her love of the world, and her humanist notions of immortality.

We always fear the unknown. I am not a coward and do not fear death, which to me means nothing more than sleep, but I cannot become resigned to leave this beautiful world with all the treasures it holds for me and for everyone who knows how to understand and appreciate them… To leave a good example to those I love [is] my only understanding of immortality.

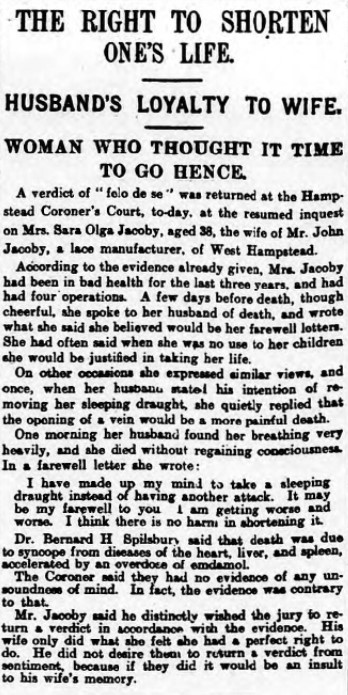

As her condition worsened, Jacoby made the decision to end her life, and took a ‘sleeping draught’ after writing letters of farewell. She died on 6 May 1913 at the age of 38. John Jacoby, testifying before the coroner’s court, argued that her death and its cause must be recorded honestly:

I distinctly wish the jury to return a verdict in accordance with the evidence. My wife only did what she felt she had a perfect right to do. If the jury returned a verdict from sentiment it would be an insult to my wife’s memory.

As such, a verdict of ‘felo de se’ – suicide – was recorded, and widely reported on by newspapers under headlines such as ‘The Right to Die’ and ‘Death Before Pain’.

Love, like strength and courage, is a strange thing; the more we give the more we find we have to give.

Olga Jacoby

Olga Jacoby’s decision to die how and when she chose sits within a long tradition of humanist advocacy for dignity in death, just as her letters embody humanism’s positive assertions about the richness of life. First published anonymously in 1919, and out of print for a century afterwards, Jacoby’s letters and their modest, honest humanism were eclipsed by the onset of the war and did not have the impact of a radical manifesto. However, they provide a fascinating glimpse into the rationalism of an average, middle class mother; a rationalism shared by thousands of men and women little remembered by history. Jacoby was a quiet pioneer of the right to die with dignity and self-determination, and a luminous example of humanism as a lived philosophy.

Words in Pain: Letters on Life and Death by Olga Jacoby, edited by Jocelyn Catty and Trevor Moore

Book Review: Words in Pain, New Humanist

Josephine Gowa was an active member of the Hampstead Ethical Institute (later Hampstead Humanist Society) for over three decades, many […]

Humanism is a way to live, to give meaning to life and to find an understanding of our place in […]

Lillie Boileau was a devoted figure within the Ethical movement, and an active part of the fight for women’s suffrage. […]

Conway Hall has effected a transformation. From the day of its opening the life of the Society has been full […]