[Ouida’s] exaggerated enthusiasms made readers smile, but they also made them think. It would be difficult to overstate the effect of her pleading for the weak things of the world, especially of the animal world, whose cause she made her own.

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt in Ouida: a Memoir by Elizabeth Lee (1914)

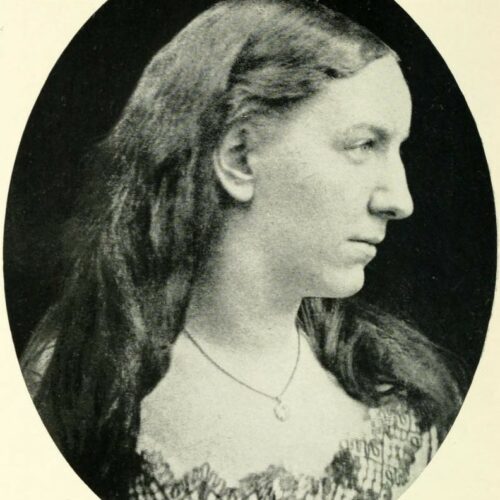

Marie Louise Ramée was an English novelist of over forty short stories, children’s books, essays, and novels. Better known as Ouida, she was one of the most prominent writers of her generation, with a career spanning five decades. She was outspoken and critical in her writings on politics, religion, and the organisation of society, but a fierce defender of animals and opponent of militarism. Her tireless activism was inspired by a firmly held sense of sympathy, justice, and responsibility for others: the ingredients of a richly humanist philosophy.

We, who are without a god, murmur to the great unknown forces of Nature: ‘Let me save others some little portion of this pain entailed on all simple and guileless things that are forced to live, without any fault of their own at their birth, or any will of their own in their begetting.’

Ouida, Ariadnê: the Story of a Dream (1877)

Ouida was the pen name of Marie Louise Ramée, born in 1839 in the Suffolk market town of Bury St Edmunds to Anglo-French parentage. Her pseudonym is widely accepted to be a childish mispronunciation of her second given name Louise, preferring it to Maria as the feminine version of her father’s name Louis. Although her father was a powerful influence on her thoughts of culture, he was often absent from her life. However, she was extremely close to her mother with whom she lived her entire life, until her mother’s death in 1893. Ouida did not marry nor have children of her own, but lived a lavish lifestyle and was renowned for the careless management of her finances and her intense love of dogs. She spent her early adult life in London, moving to Italy in her thirties where she remained until her death in 1908.

The writing talents of Ouida began to emerge in 1857 when at the age of eighteen she moved from Bury St Edmunds to London. Using her gender-neutral pseudonym to safeguard her anonymity she wrote for several magazines and three of her best novels – Strathmore (1865), Chandos (1866), and Under Two Flags (1867). These immediately established her as a natural born story-teller and at times strikingly dramatic. Among her other popular novels are Puck (1870), A Dog of Flanders (1872), Moths (1880), and Signa (1875).

Ouida successfully created and sustained a career as an unmarried, self-supporting woman with her novels featuring transgressive, independent women, and attacks on the institution of marriage. Her commitment to the cause of animal rights was specifically connected to her views on women’s abuse under patriarchy, developing strong values and beliefs on the matter of vivisection and cruelty to animals. Her outspoken opinions and views were rooted in reason, empathy, and concern for human beings and other sentient animals.

As the keeper of many dogs, Ouida had unique ideas on how they should live and be treated, attributing them moral qualities such as unselfishness and devotion. She was a pioneer in linking animal and human oppression as a multi-faceted issue and her book Puck (1870), in which a talking dog narrates his views on society, criticises the use of dogs as only ornaments of a house.

Ending animal experimentation was a cause close to Ouida’s heart and a subject she frequently wrote of in fiction, newspaper articles, and pamphlets. In a letter to Henry Drummond in 1893, she described science as having ‘brutalizing disregard of the mystery of life and its pitiless cruelty to helpless creatures’. She never passed up an opportunity to declare her views on vivisection, which she also feared would lead to the use of vulnerable humans for scientific experiments. Ouida expressed her belief in the rights of animals with an understanding that these should be merely an extension of the rights that we grant to other human beings. Of her efforts on these subjects, poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt wrote:

As a public letter-writer and pamphleteer, few women have been ever more effective than Ouida. She had a courage and a command of whirling passionate words which forced themselves on public attention. Her exaggerated enthusiasms made readers smile, but they also made them think. It would be difficult to overstate the effect of her pleading for the weak things of the world, especially of the animal world, whose cause she made her own.

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt in Ouida: a Memoir by Elizabeth Lee (1914)

Beset in her final years by poverty (though continuing to indulge a plethora of adopted dogs), Ouida was persuaded by friends to accept a civil pension in 1906. She died on 25 January 1908 in Viareggio, Italy, and was buried in the English cemetery at Bagni di Lucca.

Indifference is the invincible giant of the world.

Ouida, Signa (1875)

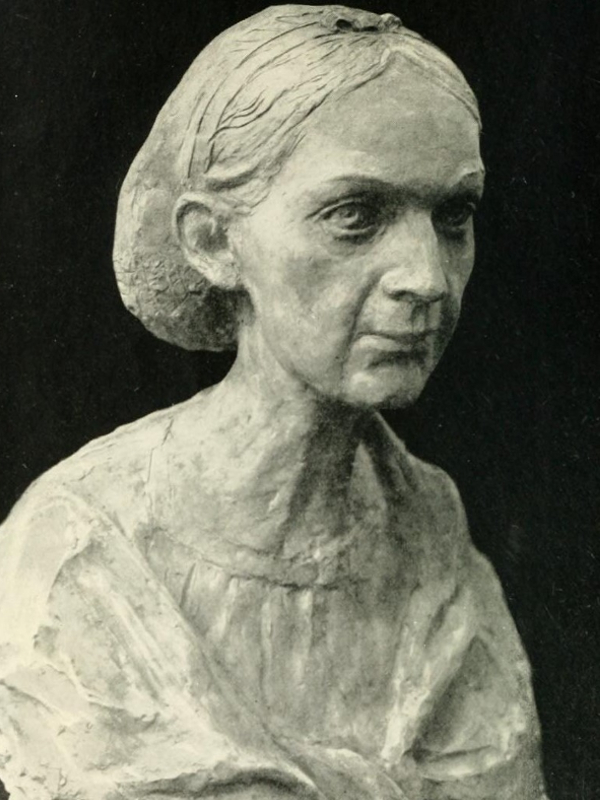

While Ouida’s passionate defence of animals and expressed hope for a ‘religion of sympathy… purer than any religion the world has yet seen, and more productive’ speak to her humanism, her legacy is a complicated one. Always eccentric, she became increasingly so throughout her life, and alienated many acquaintances and admirers with behaviour described variously as curious, arrogant, and even grotesque. Nevertheless, in a memoir published six years after Ouida’s death, Elizabeth Lee sought to brush away the ‘apocryphal stories’ which had gathered around her subject. Lee instead remembered Ouida as ‘a woman of keen intelligence, marked ability, and indomitable spirit’. She hoped that:

in any judgment we may pass on her we must never regard her only as a popular novelist. Ouida hated “All wrongdoing that is done/ Anywhere always underneath the sun”; and at a time when it was less common than it is to-day for a woman to descend into the public arena, and to plead for those who were down-trodden and oppressed, whether human beings or dumb animals, she never hesitated to espouse the cause of the suffering; moreover, she had the courage of her opinions, although they were rarely on the winning side. She advocated peace, justice to the peasant, and kindness to animals… To-day, such views are held by most civilized men and women. In congratulating ourselves on these improved conditions, let us not forget to honour the pioneers.

Elizabeth Lee, Ouida: a Memoir (1914)

Read more

Ouida: a Memoir (1914) by Elizabeth Lee

Ramée, Marie Louise de la [pseud. Ouida] | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

By Laura McGarrick

Humanism is less concerned with what to believe than with how to live. The meaning it gives to life lies […]

Conscious morality cannot exist in any being except so far as it can look behind, before, and around; and can […]

…for a long time, like the philosophers of old, I was trying to find indisputable foundations. How long it took […]

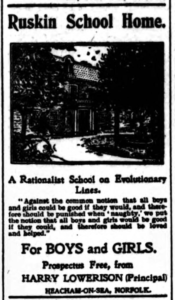

The Ruskin School Home was founded by socialist writer and teacher [Harry] Bellerby Lowerison (1863–1935) in Norfolk in 1900, following […]