Socialism emerged, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, as a humanist ideal of universal emancipation – the ideal of a communal society free of every inequality

Barbara Taylor, Eve and the New Jerusalem

Owenism was a utopian socialist movement for radical social reform, and forerunner of the cooperative movement, based on the ideas of Robert Owen. The movement began in the 1820s, its proponents championing cooperation, free thinking, and social equality; advocating a system of ‘Rational Religion’ based on reason and goodness. Many of the Owenites’ ideals were humanist ones, and find echoes in the early ethical societies which became Humanists UK. The ideas and efforts of the Owenites were part of a rich mix of 19th century secular movements, of which the ethical societies were in many ways the intellectual inheritors.

Robert Owen was a Welsh mill owner and philanthropist, whose central idea was that character was not innate, but formed according to circumstances. Poverty was not a fixed quality of certain individuals, and those problems then readily affixed to it, such as antisocial behaviour, crime, and squalor, were not inevitable facts of existence. As such, it was by changing society and its systems that the human condition could be improved. Owen tested his ideas in the New Lanark mill, reducing the length of the working day, offering educational and social opportunities to his workers, and providing schooling and meals for their children. The experiment dramatically improved the productivity of the mill. Owen’s success not only redirected his own focus towards the wider application of his ideas to society, but influenced countless others with the possibilities it suggested.

Experimental communities in the UK and overseas were started by Robert Owen and those inspired by his ideas. As Owen himself had disregarded the concepts of traditional religion, examining and finding them all wanting while still a young man, his movement was a consciously secular one. It focused on the capacity of human beings to effect change and bring about a better world, without any reference to gods: a decidedly humanist philosophy.

For its adherents, Owenism represented a striving towards ‘perfect equality and perfect freedom’, which meant equality between the sexes too. This was a particularly radical aspect of the movement for its time, and drew a number of women speakers who became prominent on the Owenite circuit, such as Emma Martin and Margaret Chappellsmith. Others even founded Owen-inspired communities, as in the case of Frances Wright, a freethinker and abolitionist who attempted to apply these values in her experimental Nashoba Community. Other Owenite settlements included New Harmony, Indiana (1825-7); Orbiston, Scotland (1825-7); Manea Fen, Cambridgeshire (1838-41); and Queenwood, Hampshire (1839).

Owenites often referred to their ideals as the ‘Rational System of Society’, rather than Owenism or Socialism, representative of their central goal: society’s complete reorganisation along rational, cooperative, and egalitarian lines. The major body of the movement was the Association of All Classes of All Nations (formed in 1835), which merged with the existing National Community Friendly Society in 1839 to become the Universal Community Society of Rational Religionists, or the Rational Society. At its peak during the 1830s and 1840s, the movement had a network of ‘social missionaries’, travelling widely to disseminate Owenite ideas. Martin, Chappellsmith, and George Jacob Holyoake were among these. In fact, it was following a lecture on Owenite principles in Gloucester that Holyoake was arrested for blasphemy in 1842.

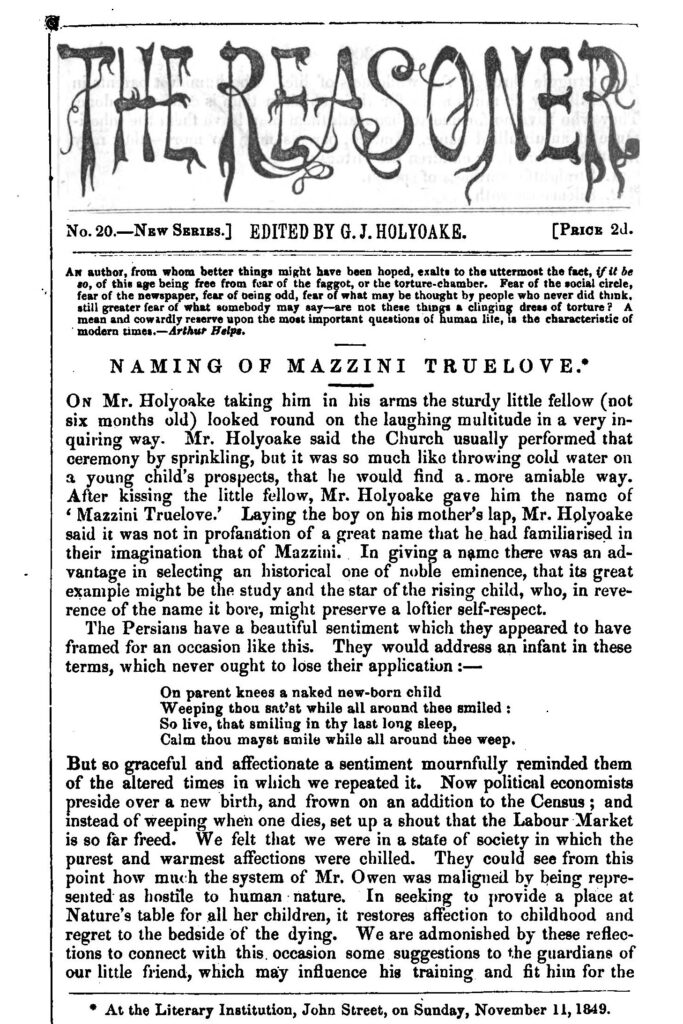

Many of those closely associated with Owenism were active champions of progressive values in other spheres of life, including the radical publisher Edward Truelove. The Owenites also performed secular ceremonies, forerunners of those conducted by humanist celebrants today, such as the public naming of Truelove’s son after Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini in 1849.

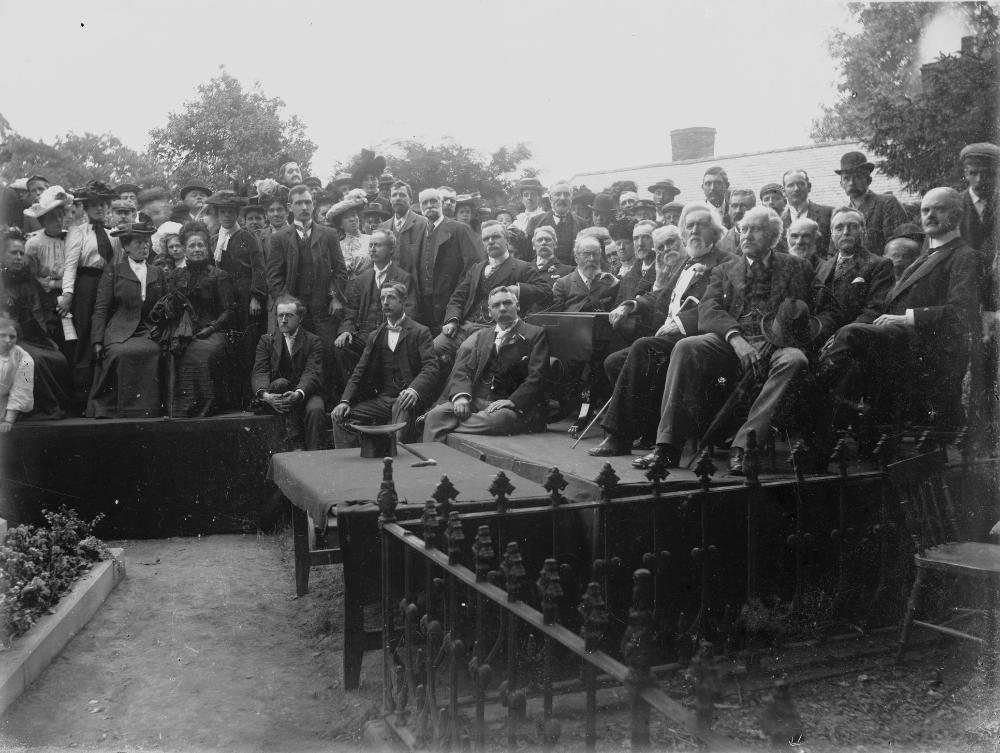

In some cases, the line between the Owenite and early Ethical movement was direct. Holyoake, for example, supported the Ethical societies, even helping to establish the Brighton group. He was also fondly remembered in a memorial service at South Place on his death in 1906, during which J.A. Hobson spoke of Holyoake’s role in the transformative efforts of reformers in the early 19th century, and the debt his generation’s humanists owed to them:

It is impossible to read the history of his early years, the thirties and forties in last century, without the feeling that one is being carried back to an age of heroic, almost miraculous, faith, an age haunted by the dreams of Shelley and of Owen, an age of unshaken belief in the present possibility of a popular Commonwealth, rid of the domination of priest and noble, guided by human reason and benevolence, and ordered for the general happiness of mankind.

Ethical Record, March 1906

As champions of secularism, freedom, and equality, and promoters of humanist values, the Owenites helped pave the way for the Ethical movement and organised humanism in the UK. In continuing to challenge restrictions on human rights and freedoms, including on speech and belief, humanists today are inheritors of this radical tradition.

The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery primarily located in London but with various satellite outstations located elsewhere in […]

No one who came in contact with her failed to recognize in her fearlessness, honesty for the sake of honesty […]

We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done. Alan […]

And in these four things, opinion of ghosts, ignorance of second causes, devotion towards what men fear, and taking of […]