Pelagius lived between the fourth and fifth centuries, and advocated a heretical Christianity that emphasised free will and humanity’s capacity for goodness. The teachings of Pelagianism were condemned in 418 at the Council of Carthage, and again by the Council of Ephesus in 431. Pelagius himself was excommunicated, and Pelagianism branded a heresy.

For many today, Pelagius’ key arguments (that humankind was not born with original sin, that people could be good without divine aid, and possessed free will to act according to their own decisions) would cause no scandal, and indeed sound distinctly humanist, but his example provides a stark reminder of the dangers of freethinking in the ‘dark ages’.

Although relatively little is known about the details of Pelagius’ life, it is generally agreed that he was born in Britain around 354. Well-educated and well-versed in holy scriptures, Pelagius incurred the wrath of the Roman Christian leaders by suggesting that human beings had the capacity to enact goodness and achieve ‘salvation’ by free will alone. Ephraim Pagitt, writing in his Heresiography, published centuries later in 1645, was content to say merely that ‘These Errors need no confutation, being so opposite to the holy Scripture’.

Pelagius believed that people could – and should – work towards goodness in this life, and indeed worried that a belief in automatic salvation after death could lead some to live less than well on earth, comforted by a false sense of security. He encouraged his followers to examine what was good and pursue it. In a letter, Pelagius wrote:

Whenever I have to speak on the subject of moral instruction and the conduct of a holy life, it is my practice first to demonstrate the power and quality of human nature and to show what it is capable of achieving, and then to go on to encourage the mind of my listener to consider the idea of different kinds of virtues.

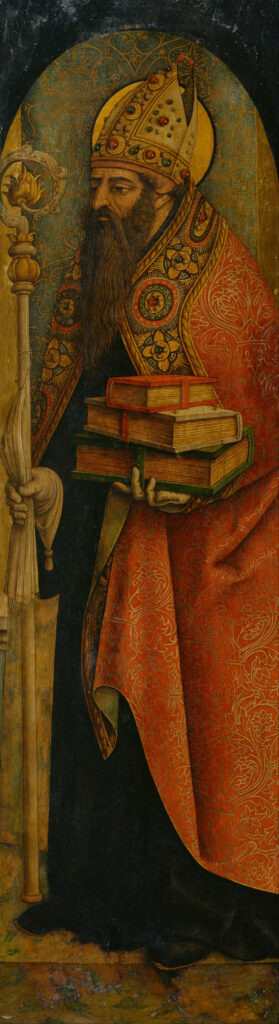

This stood in contrast to the teachings of other influential religious leaders, Saint Augustine being first among them. Augustine preached a Christianity in which God’s grace alone could save human beings from the taint of original sin, and where a person’s ultimate fate was predetermined before birth, unaffected by their good works in life. Pelagius argued instead for the importance of free will: that man, albeit assisted by divine grace, could to a far greater extent control his destiny. Augustine’s ideas were better suited to maintaining the power of the Church and the state, and Pelagius’ opponents attacked and distorted his ideas. In 418, the Pope officially declared them heresy, and Pelagius was cast out. His date of death is uncertain.

Records of figures like Pelagius, and groups like the Pelagians, refute the notion that the Middle Ages saw an absence of unorthodoxy in religious belief, or of challenges to Christianity, and emphasise the ferocity with which dissenters were dealt with for centuries in Europe. Pelagius’ focus on free will, familiar to us today, continued to cause controversy for hundreds of years after his death.

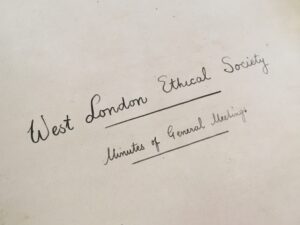

In the 18th century, Elhanan Winchester’s refutation of the idea of eternal damnation led to the formation of the dissenting group which would eventually become the humanist South Place Ethical Society. It was a willingness to pursue logic and adjust attitudes accordingly – humanist values – which enabled this evolution of thought, a tradition glimpsed 13 centuries earlier in the teachings of Pelagius.

Everywhere man blames nature and fate yet his fate is mostly but the echo of his character and passion, his […]

Virtue alone is enough to live happily and brings its own reward. John Toland, Pantheisticon (1720) John Toland was an […]

The good life… rests for its justification on no external authority, and on no system of supernatural rewards or punishments, […]

Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought […]