…a slowly growing public opinion in favour of arbitration as the alternative to war… is not in consequence of any appeal to religious sanctions; it is through the appeal to reason – the demonstration of the futility, the brutality, the economic waste, the immorality of war. It is this appeal to reason which characterizes more and more strongly the modern Peace Movement, although its adherents are not always clearly conscious of the fact.

Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, Essays Towards Peace (1913)

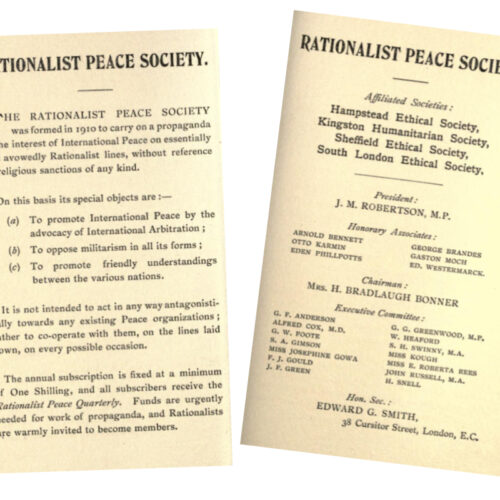

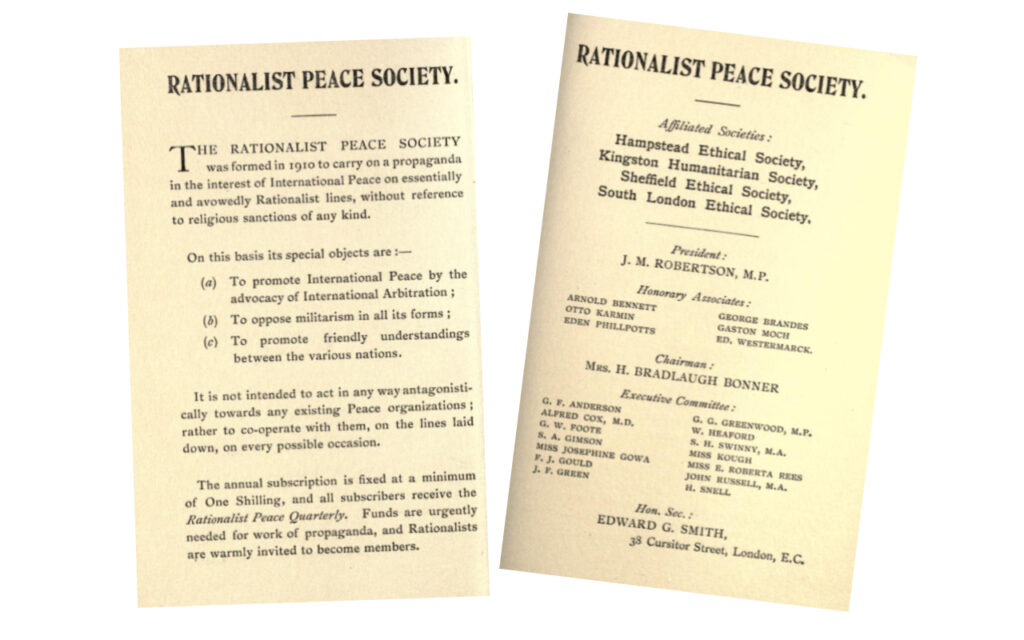

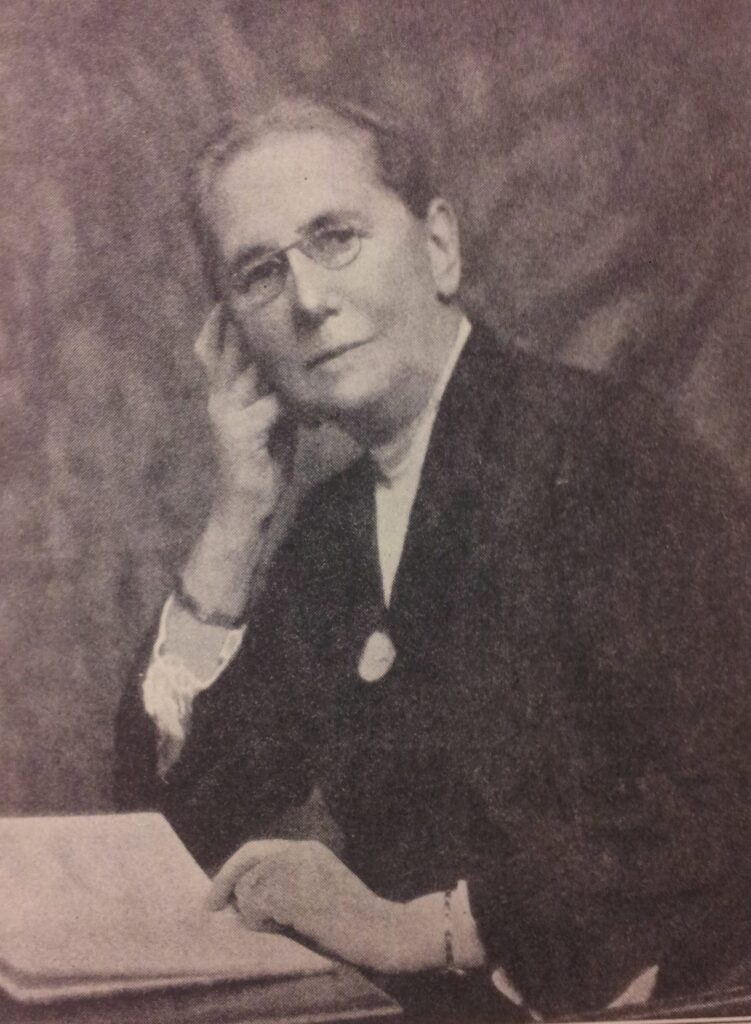

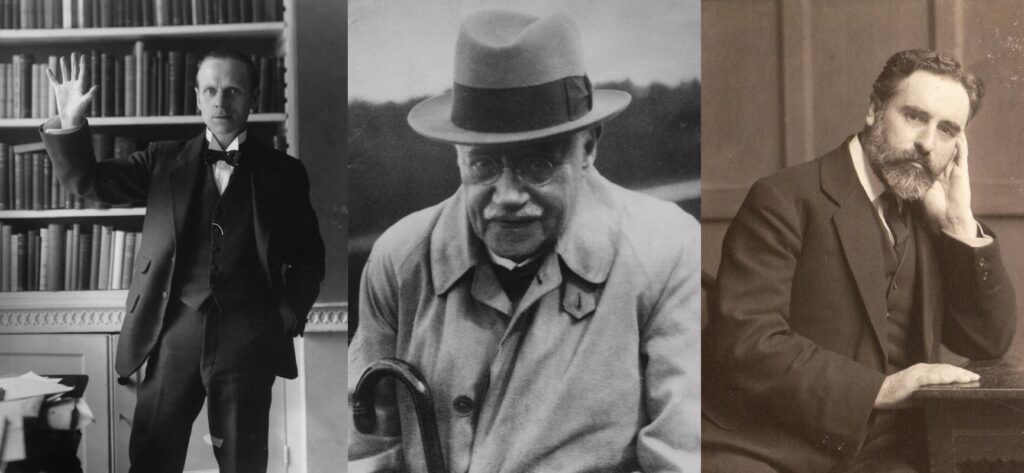

The Rationalist Peace Society was established in 1910 by Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner (a longtime Vice President of the Ethical Union, now Humanists UK), and J.M. Robertson (journalist, politician, and Appointed Lecturer at South Place Ethical Society 1907–33). The Society aimed ‘to carry on Peace propaganda on Rationalist lines,’ refuting the notion that anti-war work was the sole preserve of the religious, and working collaboratively for international peace.

Formed in the years preceding the First World War, the Society continued – and formalised – a long tradition of peace advocacy from a humanist viewpoint. As the First World War drew on, however, members became increasingly divided over matters such as conscientious objection and conscription. The Society suspended its activities in 1917, and ultimately dissolved in 1921.

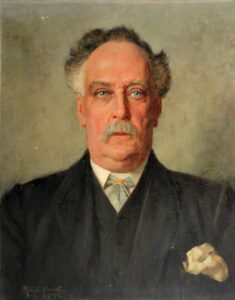

The Rationalist Peace Society was founded in 1910, and held its inaugural meeting in January 1911 at South Place, Finsbury (home of the South Place Ethical Society). Its President was the journalist, MP, and historian of freethought J.M. Robertson; its Chairman the speaker, teacher, and activist Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner; and its Honorary Secretary Edward G. Smith. Speakers at the first formal meeting included G.W. Foote and Shapland Hugh Swinny, and among the Society’s supporters were prominent humanists F.J. Gould, Harry Snell, and Henry S. Salt.

The Rationalist Peace Society sought to work for international peace ‘on avowedly Rationalist lines’, noting the long history of freethinkers’ anti-war efforts. In her introduction to the 1913 essay collection Essays Towards Peace, Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner wrote that:

…until the formation of the Rationalist Peace Society in 1910 the work of Rationalists has been merged in that of existing organizations, which are either run definitely in connection with particular religious bodies, or which associate themselves to a greater or less degree with religious influences. As a consequence, Rationalists have found their work not only annexed without acknowledgment, but actually claimed as peculiarly Christian, and have had to hear it repeated ad nauseam that Christianity is synonymous with Peace, and that none but Christian peoples abhor war.

She decried the historic willingness of supposedly religious nations (and individuals) to go to war, and bemoaned a tendency to equate the peace movement with the religious alone. In fact, she argued, humanists and rationalists throughout history had written, spoken, and acted in favour of peace and pacifism. She quoted Arthur Hobhouse (1819–1904), who in 1899 had expressed his belief that:

…there are few except the despised Rationalists and Agnostics (Atheists the Church would call them) to maintain that the moral law is the same for nations as for individuals, and that there is no higher and deeper policy than to do as we would be done by.

Bradlaugh Bonner’s list of such figures included French philosophers Pierre Bayle, Voltaire, and Denis Diderot; revolutionary writer Thomas Paine, poet P.B. Shelley, inventor of positivism Auguste Comte, RPA Honorary Associate Victor Hugo, Ralph Waldo Emerson, German physician and freethinker Ludwig Büchner, secularist pioneer Charles Bradlaugh, evolutionist Herbert Spencer, and Spanish educationist and radical Francisco Ferrer. She concluded:

The great ones now living can speak for themselves; and these, therefore, it is not necessary I should quote here. So far as the rank and file are concerned, it may be said of them that, while always ready to work for the promotion of international understanding and international goodwill, never in the whole history of the Rationalist Movement has any body of Freethinkers ever organized a meeting in support of any war, and few have ever taken part in any such meeting. The work which our predecessors have done individually and without recognition we to-day are trying to carry forward as organized propaganda.

Essays Towards Peace contained contributions from J.M. Robertson, Finnish philosopher and sociologist Edvard Westermarck, writer, MP, and anti-fascist Norman Angell (who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1933), and positivist leader Shapland Hugh Swinny.

Over the years of its existence, the Rationalist Peace Society held public meetings, took part in debates, and worked collaboratively with other peace organisations, including through the National Peace Council (the coordinating body for peace organisations in the UK). In 1913, a French Rationalist League for Peace (Ligue Rationaliste Française pour la Paix) was started in Paris, inspired by the Rationalist Peace Society. They hoped, wrote Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, ‘to co-operate in the fullest way possible with the English society in promoting the cause of international peace’.

The Rationalist Peace Society remained active during the early years of the First World War but, in 1916, in light of growing division among the peace movement, the Committee were prompted to write an open letter outlining their position. It was printed in The Literary Guide (now New Humanist), as well as in the Positivist Review, the Arbitrator, Concord, and in translation in the Libre Pensée Internationale:

A LETTER TO MEMBERS AND FRIENDS.

In view of the great divergence of opinion which has arisen within the Peace movement in regard to the present war, the Committee of the Rationalist Peace Society deem it desirable to place a plain statement of their position in the hands of the members and friends of the Society.

Most of the Committee are Pacifists of long standing who have for many years worked untiringly for the pacific settlement of international disputes. They have always firmly believed, and still firmly believe, that with the progress of civilization, and the growth of those ethical perceptions and humaner ideas which are not the least essential part of a rational civilization, there would come a day when nations would regard law as higher than war, and right higher than might.

As Pacifists, they utterly and entirely condemn all wars of aggression, whatever their excuse, regarding such wars as a base reversion to barbarism ; nevertheless, they have always recognized that there are two classes of war, which, lamentable as they must be, might yet be quite justifiable : these are wars of defence and wars of independence. In these cases it is not a choice between the right way of doing a thing and the wrong way; it is a choice of evils—the evil of submitting to force with all the demoralizing and far-reaching indignities and humiliations which too often follow in its train, or the evil of armed resistance to armed attack. By submission, men risk all that makes life worth living; by resistance, they risk life itself. Neither alternative is good ; the choice is of the lesser evil.

The Committee are aware that some members of the R.P.S. – they believe a small minority – are of opinion that under no circumstances should arms be used; that resistance should be moral, not physical. The Committee have never held, and are unable to share, this standpoint. There is no moral appeal to the ruthless barbarian, whether he be an untutored savage or a cultured one. Against attacks by these, moral resistance is absolutely ineffective. How horribly ineffective we have seen in the case of the unresisting Armenians, who have recently been so wantonly outraged and massacred by the Mohammedan ally of the Christian Germanic Empires.

The sudden outbreak of war in the summer of 1914 came as a shock to all, except to those who had planned it; it seemed the breakdown of all our hopes, the destruction of all we had worked for; but, lament it as they may, the Committee of the R.P.S. cannot see that we in this country had any alternative but to take part in it. That in the years prior to the War Great Britain, in common with other great Powers, may have been guilty of faults of omission and commission is a matter which, when the crisis came in August, 1914, could not then affect our action. The War is for Great Britain undoubtedly a war of defence: primarily of Belgium, to whom we were in honour bound, and ultimately of our own country and our own people. That we should have been drawn into this War is one of the greatest tragedies in the history of our country; but, in the opinion of the Committee, a lesser tragedy than that we also should have treated our guarantee to Belgium as a “scrap of paper,” and stood aside, forsworn, while Belgium and France were overrun.

The Committee desire to point out that, while it is futile to indulge in discussion upon the details of the terms of peace before the circumstances under which peace will be made can be known, it is exceedingly desirable that members should prepare their minds for the proper understanding of this question, the determination of which is bound to affect for good or evil the whole future of the peoples of Europe and the Near East. We want, above all, a peace which will last, which will contain within itself the seeds of peace and not the seeds of war. Eagerly as we should welcome a cessation of this awful slaughter which is draining the countries of their young manhood, a patched-up peace which caused the nations to continue to sharpen their swords and train their sons for a renewal of war would be a tragic blunder. It would, indeed, be worse than a blunder, because it would mean that we were placing upon the shoulders of our children a burden which we found unbearable. If there is yet further burden to be borne, if there is yet further sorrow to be endured, then, whatever the cost, whatever the anguish, we must bear it to the bitter end ourselves, and not pass it on, a sinister legacy of evil, to our children yet unborn.

(Signed on behalf of the Committee)

J.M. Robertson, President.

Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, Chairman.

The Rationalist Peace Society suspended its activities the following year, and was eventually dissolved in 1921. It nevertheless remains a significant, though often overlooked, part of a rich history of humanist efforts towards peace and international collaboration, founded on rationalism and compassion.

Rationalist Peace Society | Bishopsgate Institute

Avoiding alike mysticism and shallow denial, he was a true Agnostic, anxious not merely to beat down error, but to […]

Humanists have principles too, but they are principles which do not refer to the existence of the supernatural. This is […]

This article was written for Humanist News by Harold Blackham, who is viewed today as the architect of the modern […]

Virtue alone is enough to live happily and brings its own reward. John Toland, Pantheisticon (1720) John Toland was an […]