I have no view but public good; certainly no desire to injure any one, but a passionate desire to do some good in the world, so as to leave it better than I found it.

Richard Carlile, Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court, 24 November 1834

Richard Carlile was a radical publisher, a campaigner for universal suffrage, and an outspoken advocate for press freedom. He served lengthy prison sentences on charges of blasphemous libel, but continued to defend the rights of himself and others to open debate and religious denial. A key part of the radical secularist tradition, Carlile and his cooperators championed causes still upheld by humanists today: free speech, equal opportunity, and the right to unbelief. Carlile was also influential in popularising the works of Thomas Paine, particularly among the working class, as well as promoting a rational approach to sex and birth control in his publication of Every Woman’s Book.

Carlile was born in Ashburton, Devon on 9 December 1790. The second of three children born to Richard Carlile and Elizabeth (née Brookings), his father deserted the family while still young, and his mother – a devout Anglican – raised her children in strict Christianity. Carlile received his early education at two local schools, leaving at the age of twelve to begin working.

As a young man he was apprenticed as a tinsmith and moved to London to follow his trade, but a recession and competition from factory produced goods led him into bookselling and an acquaintance with the works of radicals such as Thomas Paine. In 1817 he took over a journal entitled Sherwin’s Political Register and opened his own bookshop and publishers on Fleet Street.

On 16 August 1819 Carlile was in Manchester and was a part of the platform party at Peterloo when the yeomanry charged. He was appalled by what he witnessed, particularly the violence shown to women. Unlike many of the other prominent radicals in attendance, he avoided arrest, and returned to London to become one of the first to publish furious denunciations of what had occurred. When the authorities closed down Sherwin’s Political Register, he simply carried on by founding a new journal, The Republican, with its far more provocative title. He also published his iconic print of Peterloo, which he dedicated to Henry Hunt (the speaker at Peterloo) and the female reformers of Manchester.

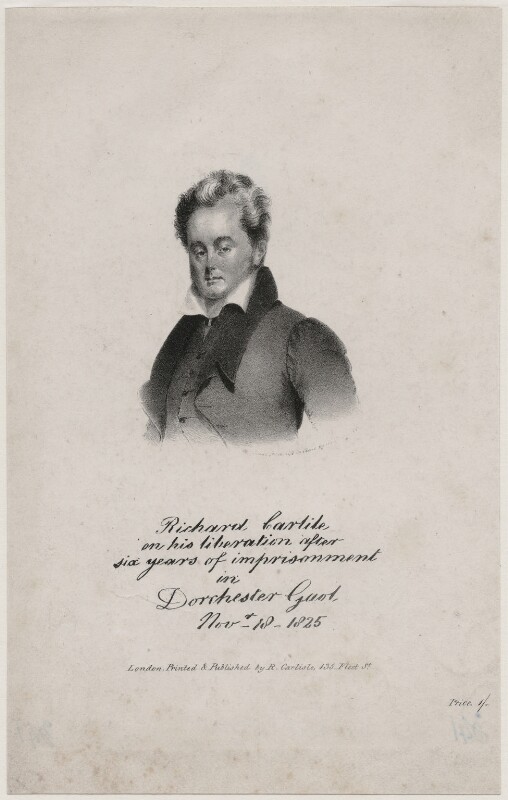

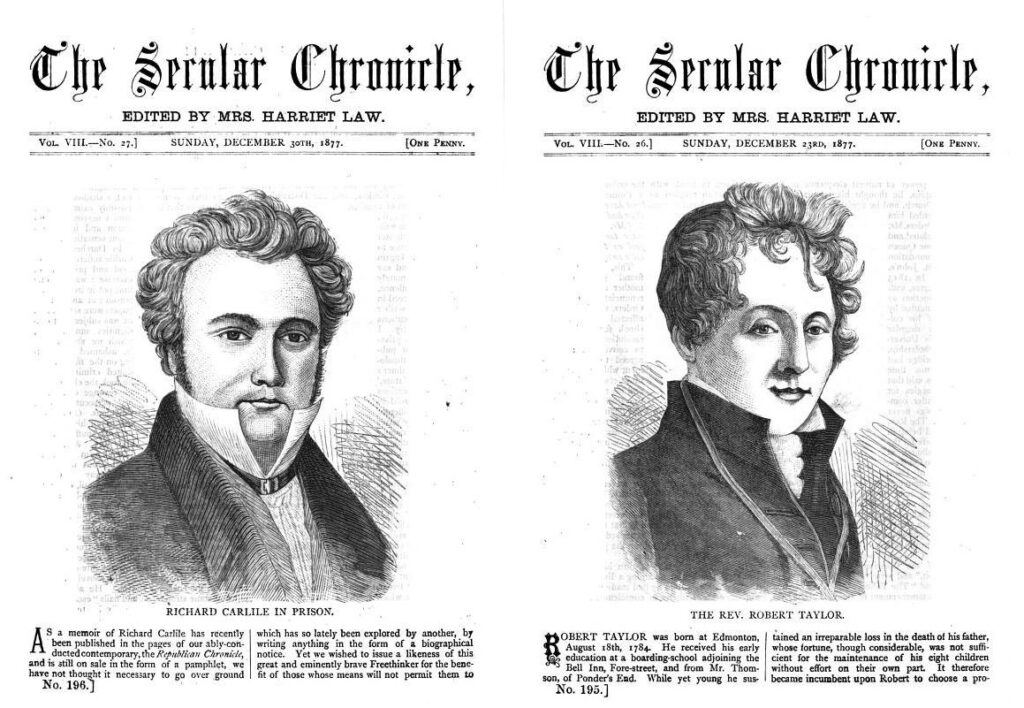

The authorities would not let matters rest here. Carlile was prosecuted for publishing Paine’s The Age of Reason, sentenced to three years in Dorchester prison and fined £1,500, a huge sum. He actually served seven years because of his failure to pay the fine. It was during this period that Carlile achieved his greatest fame. Prison was very different then and Carlile had wealthy supporters who were able to buy better food and a comfortable cell. During his incarceration he continued to edit The Republican while back in London his wife, Jane, managed the bookselling and publishing business.

During his time in gaol, others continued his work distributing and selling his publications. For a time his sister and wife joined him and a child was conceived and born. No fewer than 150 others were also imprisoned for working in his Fleet Street premises and selling his publications.

In 1825 the authorities gave up the struggle, realising that their persecution of Carlile was only drawing attention to his campaigns, and he was released.

Carlile was undaunted. Soon after release he took out a lease on larger premises at 62 Fleet Street. He was to call the premises his the ‘Temple of Reason’. He soon followed this by publishing his own book, Every Woman’s Book, which advocated contraception and gave practical advice on technique. It was the first book in English to do so. Perhaps more startling, he argued sex was a healthy pleasurable activity, even for women! Carlile was driven by a number of motives. Not only did he regard large families as a cause of poverty but considered Christian sexual morality repressive of women.

Between 1827 and 1829 Carlile went on four national lecture tours (‘infidel missions’). On one of these he was joined by the Rev. Robert Taylor (the Devil’s Chaplain). This proved particularly popular and together they attracted large crowds. In 1830 he opened the Rotunda on Blackfriars Road, which became a centre of radical theological and political discussion. By 1831 he was back in prison for seditious libel, having published writings in support of agricultural workers protesting increasing mechanisation and harsh working conditions (an uprising known as the Swing riots).

Sadly, Richard was to become estranged from his first wife, Jane, and found a new partner (‘moral wife’) Eliza Sharples. Eliza was an extraordinary character herself, becoming the first woman to give freethought lectures and to edit a freethought journal. After Carlile’s death, in 1849, Eliza provided shelter for the 16 year old Charles Bradlaugh after he left home in acrimonious circumstances.

Carlile lived for another 10 years. He was imprisoned once more, serving a couple of months for causing a public nuisance by refusing to pay church rates and displaying blasphemous effigies in his shop window.

Richard Carlile died on Fleet Street on 10 February 1843. Nearly 10 years of his life were spent in prison.

Carlile’s career marks a significant contribution to the development of humanism. His publishing business helped keep the works and ideas of Thomas Paine and others alive, and made them accessible to those with fewer financial means. His heroic defiance of the Church and state helped demarcate the boundaries between the secular and the religious. He was a feminist, an advocate of women’s rights, and he dedicated his life to the freedom of the press and expression.

By Robert Forder

Our interest, it seems to me, lies with so much of the past as may serve to guide our actions […]

This article appeared in The Secular Chronicle (Vol. V, No. 1), 2 January 1876. It marked the first issue edited […]

Robert Owen was a utopian socialist, philanthropist, and reformer, whose own religious scepticism fostered his desire for a secular society, […]

The attainment of the greatest possible amount of social happiness I take to be the noblest of human aims; the […]