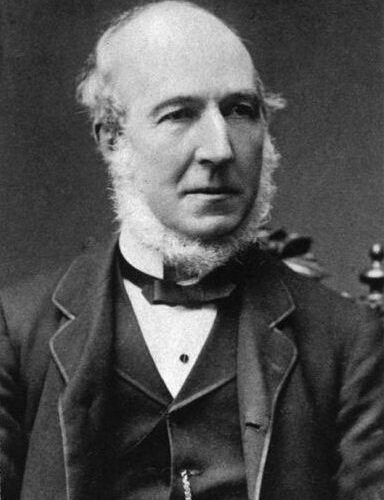

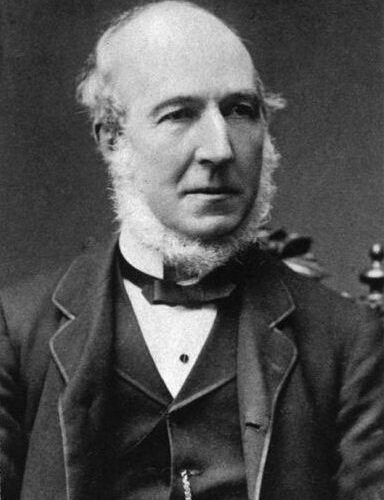

Richard Congreve was a devoted follower of Auguste Comte, whose positivist philosophies and ‘Religion of Humanity’ inspired Congreve to open his own ‘positivist temple’ in 1870. Here, he told his congregants, they met ‘as believers in humanity’. Some followers of, and later breakaways from, Congreve’s ideas were also members of the ethical societies (most notably Frederic Harrison), and positivist beliefs were influential in the humanist Ethical movement.

Richard Congreve was born in Warwickshire in 1818, the son of a farmer. His early schooling, including at Rugby School (1832-7) influenced his moral, political, and liberal leanings. From 1837, he attended Wadham College, Oxford, earning his BA in literae humaniores in 1840. This was followed by an MA in 1843. While at Oxford, as well as acting as President of the Oxford Union in 1841, Congreve was active in debating society ‘the Decade’, among whose other members was Matthew Arnold. He took clerical orders in 1843 and became a fellow of Wadham College the following year. From 1848, he was a tutor at the College, and was an active participant in efforts towards university reform.

Congreve was drawn to the ideas of Auguste Comte, and visited the philosopher a number of times in Paris, encouraged by him to make further study of positivist ideals and their applications. Resigning his Oxford fellowship in 1854, Congreve moved to Wandsworth, Surrey, and in the same year married Maria Bury, his cousin. Through her, Congreve became acquainted with George Eliot and George Henry Lewes, who settled nearby in 1859. The couple supported Congreve’s positivist efforts, through their friendship as well as financial help. In 1857, Comte himself had made Congreve the head of his British followers.

In 1870, along with former pupils and fellow positivists Frederic Harrison, J. H. Bridges, and Edward Spencer Beesly, and others, Congreve leased a hall on Chapel Street, off Lamb’s Conduit Street, London (today 20 Rugby Street), which they opened as a ‘Positivist School’. Here, discourses were delivered ‘ranging over all the subjects of human interest, all questions of social and personal duty.’ The ideals of the group were summed up in their central maxims:

Love our principle, Order the basis, Progress the end. Live for others, Live openly.

The positivists’ rejection of theological belief meant a disavowal of the religious education of children, just as it did for members of the Ethical movement, who advocated for moral rather than religious instruction from the movement’s earliest days. Congreve established a ‘free school’ in response to the legal requirements of religious education in primary schools which, as David Rosenberg has written, had the ‘unanticipated’ function of ‘teach[ing] English to children of radical refugees, who had fled from France after the Paris Commune was crushed in 1871.’

In 1878, Congreve’s disavowal of the positivist leader in Paris, Pierre Laffitte, saw a decisive (though long anticipated) schism in the movement in England. His early and distinguished devotees, Harrison, Bridges, and Beesly, left to found a positivist centre of their own at Newton Hall. Congreve continued to lead the Chapel Street congregation, designating it the Church of Humanity, and introducing a greater degree of ritual and ceremony to his services there. This element of his positivist teachings garnered a withering response from some, including T.H. Huxley, who saw in this ‘philosophy in practice’ merely ‘Catholicism minus Christianity’.

Congreve continued to write and to lead his followers until his death in Hampstead on 5 July 1899. Following the death of his widow in 1915, the divided positivist congregations united.

Our ideal, our aspiration, is purely human.

Congreve and the ideas of positivism had a direct influence on individuals within the developing organised humanist movement, such as Frederick James Gould, who wrote in his Life Story of a Humanist that: ‘No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, and Order for basis; Progress for aim.” Gould felt that ‘Comte’s splendid maxim… “Act from affection, and think in order to act” … combines, in a flash, Love and Rationalism and Character in one social and all-embracing purpose.’ These concepts of love for humankind, faith in reason, and the development of moral character, animated the Ethical movement, and remain central to the humanist approach today.

I have no view but public good; certainly no desire to injure any one, but a passionate desire to do […]

The actress turned campaigner and human rights activist Sylvia Scaffardi was a co-founder of The Council of Civil Liberties, along […]

Elhanan Winchester was the first minister of the dissenting congregation that eventually became the humanist South Place Ethical Society in […]

Harry Stopes-Roe was one of the most tireless and dedicated humanist campaigners of the 20th century. Son of the influential […]