Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays.

Baroness Sally Greengross, ‘Do we need specific human rights for older people?’ (2020)

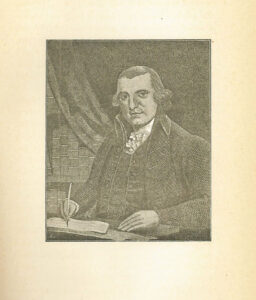

Humanist and patron of Humanists UK Sally Greengross was a fierce champion of the rights of older people, whose tireless work helped to challenge discrimination and transform attitudes to ageing in the UK.

Anything we recognise as finite can become more acutely pleasurable, and, as the prospect of available time decreases, the desire to experience life fully and to enjoy all it has to offer may well increase.

Sally Greengross, Ageing: an Adventure in Living (1985)

Born in 1935 to secular Jewish parents, Sally Greengross grew up in Brighton and attended the London School of Economics and Political Science. Always passionate about Europe and Internationalism, she spent her early career working as a lecturer and researcher on European Affairs. In 1959 she wed husband Alan Greengross, and together they had four children and nine grandchildren. A family friend recalls Greengross raising her family in line with her humanist beliefs, with one of her children’s few rules being ‘that they should on no account become fundamentalist about anything.’

Sally Greengross is perhaps most famous for her influential work as Director General of Age Concern (now part of Age UK) for 13 years. She was also joint chair for the Institute of Gerontology at King’s College London, chair of the New Dynamics of Ageing research initiative, and the Secretary General of Eurolink Age. In her later career she worked as the president and chief executive of the International Longevity Centre-UK, an influential think tank she established in 1997. She was also the founder and later a patron of the elder abuse charity Hourglass.

Greengross had a successful political career, becoming an independent member of the House of Lords and raised to peerage in the year 2000. She chaired the cross-party Intergenerational Fairness Forum and was the founding commissioner of the Equality and Human Rights Commission from 2006 to 2012. Greengross’ humanist beliefs greatly informed her contributions in the House of Lords, and she was a valued member of the All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group (APPHG). In 2022 she signed a joint letter urging the UK Government to recognise humanist marriages in England and Wales. Her other humanist priorities included the right for terminally and incurably suffering adults to end their lives, and she spoke at the second reading of the Assisted Dying Bill advocating her support. As recently as March 2021 she signed a joint letter calling for a review into the UK’s laws on assisted dying.

Greengross greatly challenged the proposal to create a separate bill for the rights of older people, on the principle that universal rights should apply to everybody, arguing ‘At what age will someone become an older person and no longer have the human rights of an adult?’. She believed that age discrimination in the UK remains a significant problem to be tackled and worked tirelessly towards the defence of human rights right up until the end of her life. Just two days before she died Greengross wrote to Prime Minister Boris Johnson on behalf of Hourglass: ‘I am coming to the end of my life,’ she said. ‘I am writing to you in the hope that you will help this important charity so that the work that I started all those years ago can be continued.’

How much better it would be if everyone accepted older people without stereotyping them. They may be pleasant or unpleasant, good, bad or indifferent, but are as distinct and distinguishable from each other as are people of any other age group.

Sally Greengross, Ageing: an Adventure in Living (1985)

In their obituary, Hourglass reflected: ‘There are few people who have championed the rights and protections needed for older people as passionately and committedly as Baroness Sally Greengross.’

Inspired by her strong humanist conviction that every human being was possessed of equal and unconditional human rights, Sally Greengross was someone who worked successfully in politics to improve the lives of thousands of people across the UK. In doing so she left a profound legacy to future generations: a deep political consensus on the value of elders’ rights, the ongoing sustainability of charities like Age UK and Hourglass, and increased awareness and efforts across civil society to tackle issues facing older people, now and into the future.

Remembering Baroness Greengross | Humanists UK

Lady Greengross obituary | The Guardian

Ageing: an Adventure in Living edited by Sally Greengross (1985)

By Alex Woodward

Main image: Baroness Greengross, UK Parliament. Licensed CC BY 3.0

Elhanan Winchester was the first minister of the dissenting congregation that eventually became the humanist South Place Ethical Society in […]

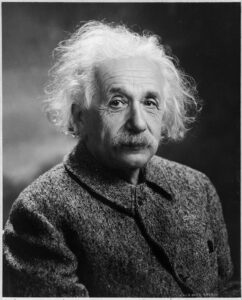

How strange is the lot of us mortals! Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose […]

William Pirrie Barbour was a classicist, codebreaker, teacher, and activist. A rationalist and humanist, Barbour championed integrated education in his […]

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]