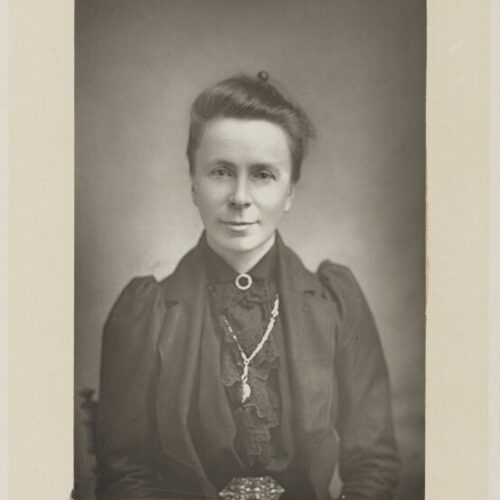

Sophie Bryant was an Anglo-Irish mathematician, feminist, suffragist, teacher, and promoter of moral education. She played a key role in founding the London School of Philosophy, which arose from the London Ethical Society, and sought to make the teaching of philosophy practical and accessible. In a life devoted to inclusive education, political equality, and the application of reason, she was part of a rich tradition of pioneering humanist women who applied their values to the pursuit of progressive social reform.

Sophie Bryant was born near Dublin on 15 February 1850. She was one of six children born to Reverend William Alexander Willcock, a mathematician and fellow of Trinity College, who was responsible for her early education. In 1866, she was awarded a scholarship to Bedford College, London.

Sophie Willcock married William Hicks Bryant, a doctor, in 1869, who tragically died just a year later. From 1875, she worked at the North London Collegiate School, run by pioneer of women’s education Frances Buss, where she taught mathematics. In this, she helped to break down stereotypical notions of maths as a subject unsuited for girls, not least by sending a number of her students on to Girton College, Cambridge. Bryant herself had placed first class in the Cambridge local examinations several years before.

Bryant achieved her own bachelor’s degree in 1881, one of the first two women to graduate from the University of London with a BSc. Three years later she became the first woman in the UK to be awarded a DSc. Passionate about education and its inclusiveness, she played a key role in establishing the London School of Ethics and Social Philosophy in 1897. This was an initiative of the London Ethical Society, of which she was an early and active member, who sought to increase access to higher education for all. The London Ethical Society, the UK’s first, advocated living moral lives without reference to theological beliefs, and sought close cooperation with existing bodies (such as the Working Men’s Colleges) who shared their educational aims.

In 1895, she succeeded Frances Buss as head of the North London Collegiate School, where she remained a distinguished and admired educator until her retirement in 1918. During this time, she continued to champion improvements in education, and her role as a pioneer, becoming the first woman elected to the senate of London University. Here, she promoted the formation of the London Day Training College, a teacher training body established in 1902.

Bryant’s passion for freedom in all areas of existence informed her personal and professional life. She was president of her local branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and a longtime advocate of women’s right to participate in public and academic life. She was physically active to her very last years: cycling, rowing, and hiking. It was during a climbing holiday in the Alps in 1922 that she lost her life.

By her own example and through her efforts for wider social change, Sophie Bryant was a pioneer of women’s education. Like her contemporaries in the ethical movement – among them the champion of co-education Alice Woods – Bryant applied a rigorous intellect and deeply felt sense of justice to bringing about progressive reform. As an educator, and as the third woman elected to the London Mathematical Society, she blazed a trail for women in the study of maths, but pursued a full life that was so much more than just academic achievement.

In her longtime concern for moral, non-theological education, her efforts towards an inclusive and just society, and her clear belief that these could be achieved without supernatural sanction, Sophie Bryant lived an inspiring humanist life. These beliefs remain central to the work of Humanists UK today.

The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery primarily located in London but with various satellite outstations located elsewhere in […]

By Mia Nathan Constantly having to combat irrational and dangerous thinking is strenuous and sometimes tedious, but not necessarily boring. […]

I believe in the supreme virtue of exploring. I believe in finding out. Even if I don’t succeed, I still […]

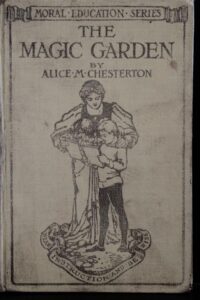

Its aim will be to secularise education and make moral training the chief aim of the school life. A great […]