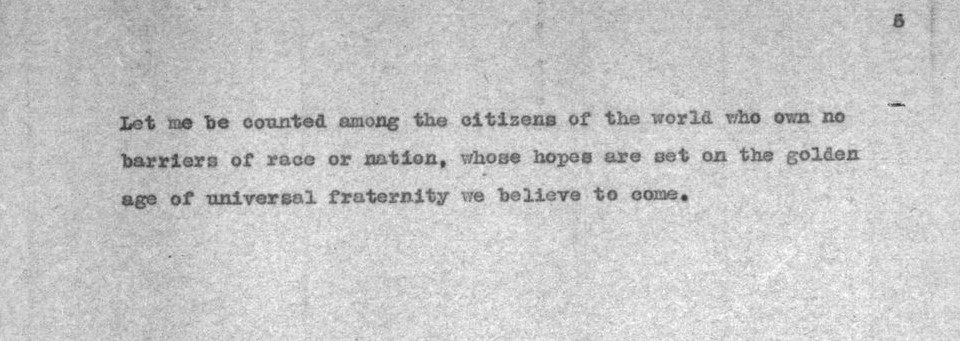

Against the militarist totalitarian state, I have striven. For the freedom of the human spirit to develop under the kindly stimulus of mutual aid and service, I will always stand. Let me be counted among the citizens of the world who own no barriers of race or nation, whose hopes are set on the golden age of universal fraternity we believe to come.

Sylvia Pankhurst, ‘What would I wish to be known and thought of me when I am gone?’, typescript in the Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst Papers, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam

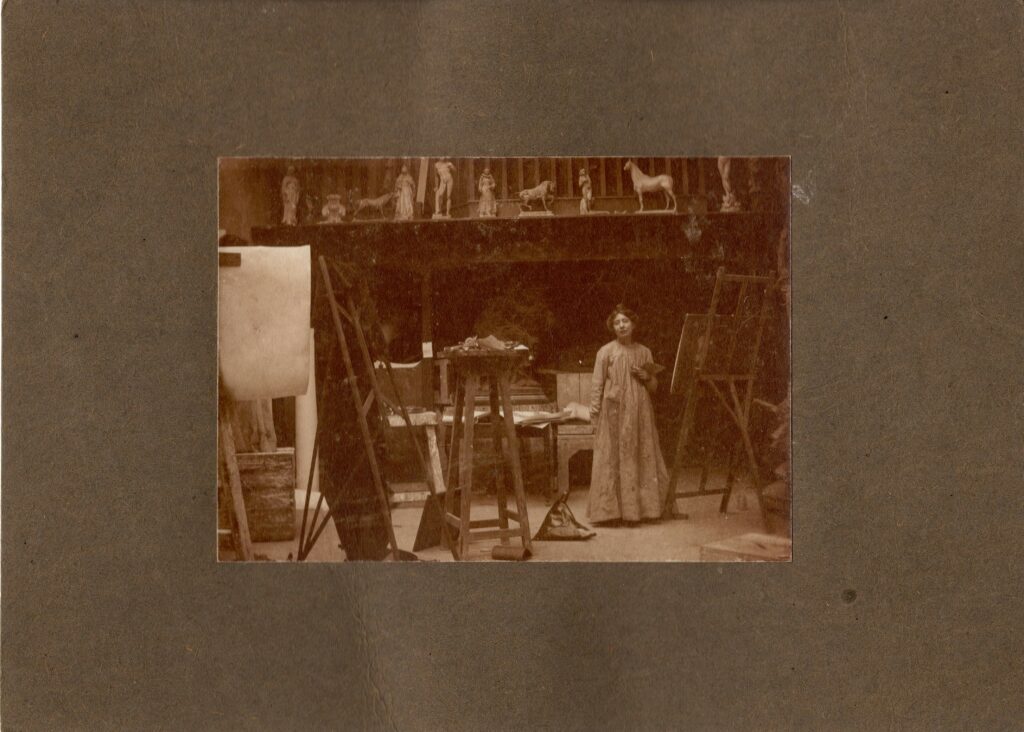

Sylvia Pankhurst was a feminist, a socialist and a humanitarian. Driven by an all-embracing compassion and an acute sense of justice, she abandoned a successful artistic career to campaign for the rights of working women in London’s East End, and then more widely on behalf of the oppressed and disadvantaged wherever she found them. Guided by her humanist values, her life was one of resolute and uncompromising service to humanity.

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst was born in Manchester, the second daughter of the future militant suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst and the radical lawyer Dr Richard Pankhurst. The Pankhurst family home was a meeting place for intellectuals and political activists, so while she was still young Pankhurst met among others Annie Besant, the American feminist Harriot Stanton Blatch, and William Morris – who exerted great artistic and political influence on her. Pankhurst was also profoundly influenced by her father’s progressive ideals and she strove always to live up to his admonition: ‘If you do not work for others you will not have been worth the upbringing’. She also acquired from her father her lifelong atheism.

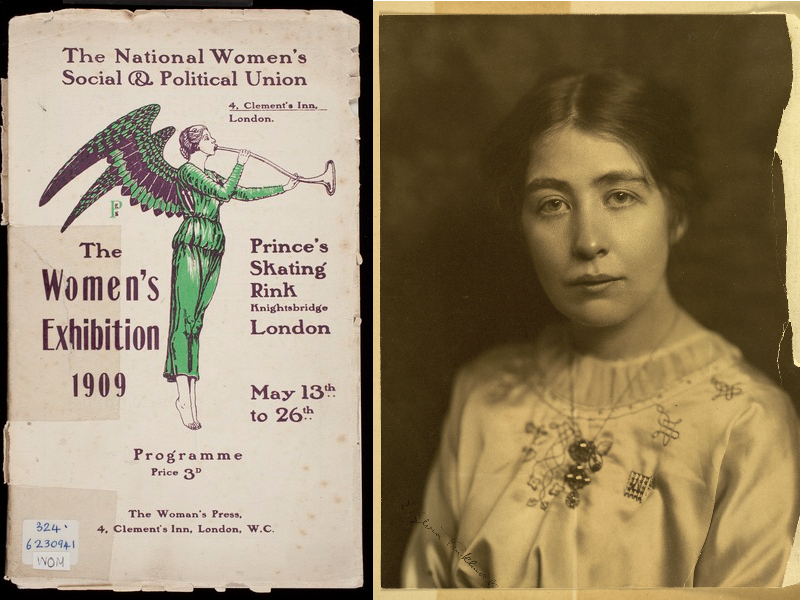

Pankhurst attended Manchester High School for Girls and trained as a scholarship student at both the Manchester Municipal School of Art and the Royal College of Art. On graduation she supported herself by selling her paintings and textile designs, and made a tour of industrial areas to paint portraits of working women. She also designed murals, banners, regalia and merchandise for the suffragette Women’s Social and Political Union, including the famous ‘Angel of Freedom’ motif. An exhibition of Pankhurst’s work took place at Tate Modern in 2013-14.

I wanted life to be a great adventure, in which every shred of one’s energy would be poured into some chosen work of beauty and value.

Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement (1931)

In 1912 Pankhurst abandoned her artistic career in favour of politics. She built an independent women’s suffrage movement in London’s docklands, was repeatedly arrested while campaigning for the vote and, in solidarity with other suffragettes, went on hunger-strike in prison and was force-fed. But she opposed the WSPU’s increasing violence, believing that the best way forward lay in creating a mass movement of women campaigning together with men for universal adult suffrage.

During the First World War, Pankhurst concentrated on relief work in the East End. She created mother-and-baby clinics, a child-care centre, cost-price communal restaurants and small local enterprises to provide employment. She lobbied government to ensure that soldier’s wives received their benefit entitlements, and campaigned for women employed on war work to be paid the same as men. She supported conscientious objectors and interned ‘enemy aliens’, and spoke out courageously both against conscription and against the war itself.

I believed that an end to the war without victory for either side, would be best for the world and the people, and the sooner it came the better.

Sylvia Pankhurst, The Home Front (1932)

Pankhurst became increasingly radical following the 1917 Russian revolution. She attended the Second Congress of the Third Communist International in Moscow but found herself side-lined after she refused to let the Communist Party take control of her newspaper the Workers’ Dreadnought. She then abandoned revolutionary politics and focused on writing books, notably Save the Mothers (1930), an appeal for better maternity services. She also worked to promote an international language as a vehicle for world harmony.

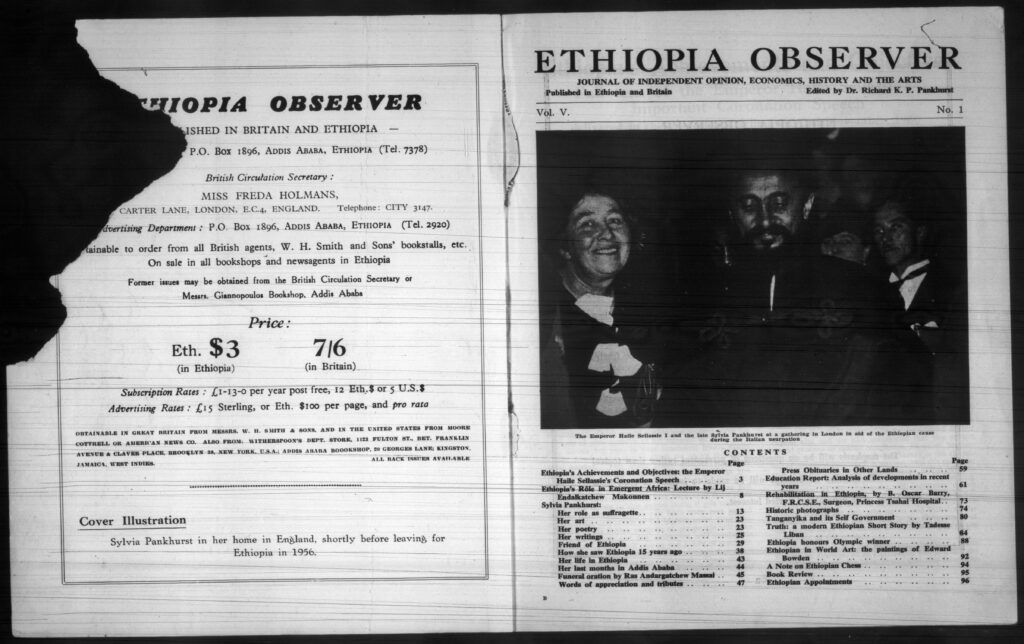

The rise of fascism in the 1930s led Pankhurst to return to active politics. Following the Italian invasion of Ethiopia she launched a weekly journal to support the Ethiopian people in their resistance to Italian rule, and her commitment to the country continued after the war. She raised enough money to build Ethiopia’s first teaching hospital and in 1956 relocated to Addis Ababa where she edited the Ethiopia Observer and helped to establish local social services. On her death in 1960 she was given the remarkable honour of a state funeral attended by the Ethiopian royal family.

By the work I have accomplished, by the opinions I have helped to create, the people I have influenced, I shall live on when my name has been forgotten.

Sylvia Pankhurst, ‘Now that I am nearly fifty’ quoted by Patricia W. Romero in E. Sylvia Pankhurst: Portrait of a Radical (1987)

Sylvia Pankhurst had an uncompromising conviction that both individuals and communities have a shared responsibility for everybody’s welfare. She resolutely refused to differentiate between people on grounds of sex, class or colour, placing her intelligence, courage, energy and vision at the service of all. Intensely altruistic, there seemed to be no limit to the sacrifices she was willing to make for others. She was ‘a devoted daughter of humanity’, and a humanist, whose influence has always been the example of her life.

E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement (1931)

The Workers’ Dreadnought | LSE Digital Library

Richard Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst: Artist and Crusader (1979)

Rachel Holmes, Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel (2020)

Heritage Trail | East End Women’s Museum

By Paul Ewans

Many human beings are sensible and friendly and kind; able to combine together to carry out wise policies. It is […]

Nina Spiller was a lifelong worker for women’s rights, who played an active role in the humanist movement for more […]

All religious theories, schemes and systems, which embrace notions of cosmogony, or which otherwise reach into the domain of science, […]

Godlessness is negative. It merely denies the existence of god. Atheism is positive. It asserts the condition that results from […]