Not by the Creed but by the Deed.

Motto of the Society for Ethical Culture of New York, founded in 1876

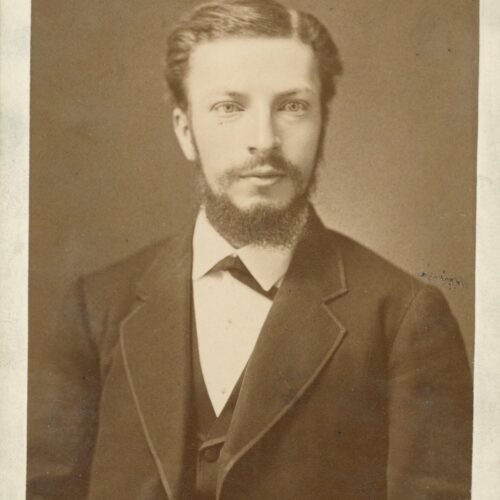

The Ethical movement formally began in America in 1876, when Felix Adler – a rabbi’s son – founded the Society for Ethical Culture in New York. Its focus was on living rich and moral lives without reference to religious doctrines or supernatural beliefs, and was the beginning of organised humanism as we know it today. The first Society for Ethical Culture, and all of those that followed, believed in establishing clear ethical principles for living moral lives, and supporting one another in doing so. As such, the societies also had a social function.

A belief in the importance of deed meant acting morally for its own sake, and working to make a difference with the one life you could be sure of. This led Adler and the adherents of Ethical Culture towards charitable efforts and social reform, as well as the provision of education and improved access to healthcare. All of these things would be continued as the movement grew and developed, including in the UK ethical societies (now Humanists UK).

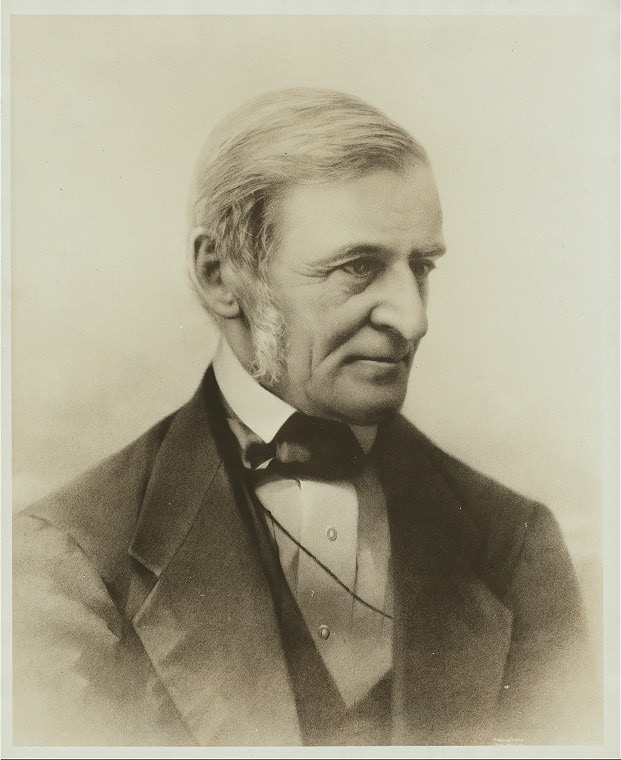

In conceiving Ethical Culture, his secular, inclusive, and practical ‘religion’, Adler had been notably influenced by two key figures: Immanuel Kant and Ralph Waldo Emerson. From Kant, he absorbed an idea of the impossibility of proving the existence of god through reason, and the possibility of developing a sense of morality distinct from supernatural belief. Through Ralph Waldo Emerson, Adler was introduced to the concept of ‘Free Religion’. The Free Religious Association had been formed in 1867 by a group including suffragist Lucretia Mott, emphasising reason and individual conscience.

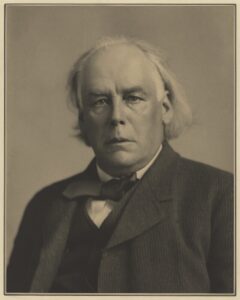

Although he downplayed the extent of Emerson’s influence on his own philosophy, the ideas of a ‘religion’ of ethics, and a focus on self-reliance, echo those of Emerson and his circle. Others in the movement, notably Moncure Conway, were also among Emerson’s admirers.

Another influential figure in the early Ethical movement was William Mackintire Salter (1853–1931), a philosopher and author who founded the Chicago Society for Ethical Culture in the early 1880s. His 1899 Ethical Religion helped to spread the ideas of the societies and of Adler, to whom Salter acknowledged an ‘intellectual indebtedness… so great that it would be difficult to measure it’. Mahatma Gandhi would later translate a number of chapters from Ethical Religion into Gujarati, publishing them in Indian Opinion.

The use of the term ‘religion’ to describe the burgeoning humanist movement has always been a matter of debate. Like Felix Adler, who felt that in its ‘broader sense religion means zealousness and devotion to something supreme’, later leaders of the ethical societies sought sometimes to remove, and sometimes to redefine, ‘religion’ to suit a secular moral movement. In the case of some, religion merely meant the pursuit of the ‘good’ and ‘true’, quite distinct from any notions of a god.

The UK’s first ethical society was formed in London in 1886 by a small group, inspired both by the American movement, and by philosophers like T.H. Green at Oxford. 1888 saw the formation of a society in Cambridge, led by Henry Sidgwick, as well as the succession of Stanton Coit to the leadership of South Place, which formally became an ethical society (rather than a ‘religious’ one).

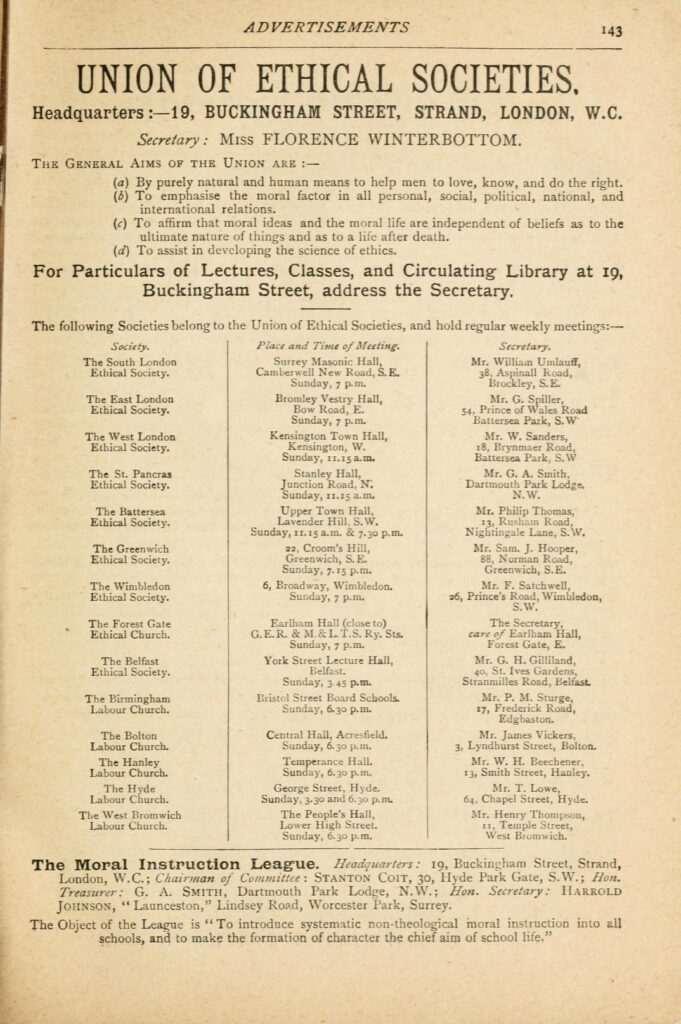

More groups followed. In 1896, the Union of Ethical Societies was formed to jointly promote right living on a rational basis, without reference to supernatural punishment or reward. In the same year, an international conference took place in Zurich, with representatives from the English, American, and European societies of the Ethical movement. This strand of internationalism was a common thread running through the movement from its beginnings, and remains a key part of humanism today, exemplified by the work of Humanists International, and in the humanist impulses behind bodies such as UNESCO.

The Ethical movement grew and spread, with societies appearing throughout the UK. Other groups with a shared humanist outlook also became affiliated with the Union, such as the Humanitarian League, the Howard League, and the Progressive League, all of which advocated humane and forward-looking social reform.

In 1920, the Union of Ethical Societies became the Ethical Union, and in 1967 the British Humanist Association. Since 2017, it has been known as Humanists UK.

For a visual tour of this history, see 125 Years of Humanists UK.

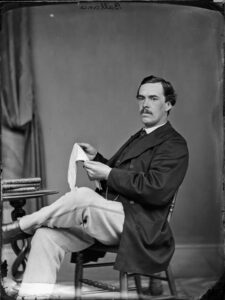

The National Secular Society is a campaigning organisation, founded in 1866 to champion the principles of secularism and the separation […]

When Nigel Lawson said in 1992 that the National Health Service was the ‘closest thing the English have to a […]

I believe in the absolute equality of the sexes, and I think they [women] should be in the enjoyment of […]

The British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) began as the Birmingham Pregnancy Advisory Service, created to provide access to safe, legal, […]