And in these four things, opinion of ghosts, ignorance of second causes, devotion towards what men fear, and taking of things casual for prognostics, consisteth the natural seed of religion; which, by reason of the different fancies, judgements, and passions of several men, hath grown up into ceremonies so different that those which are used by one man are for the most part ridiculous to another.

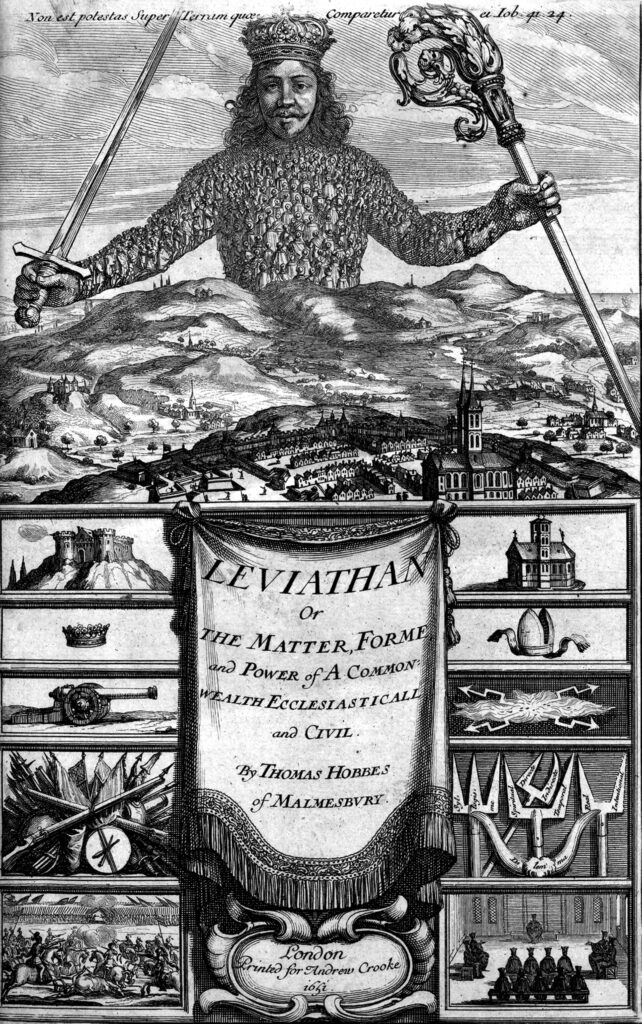

Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes (1651)

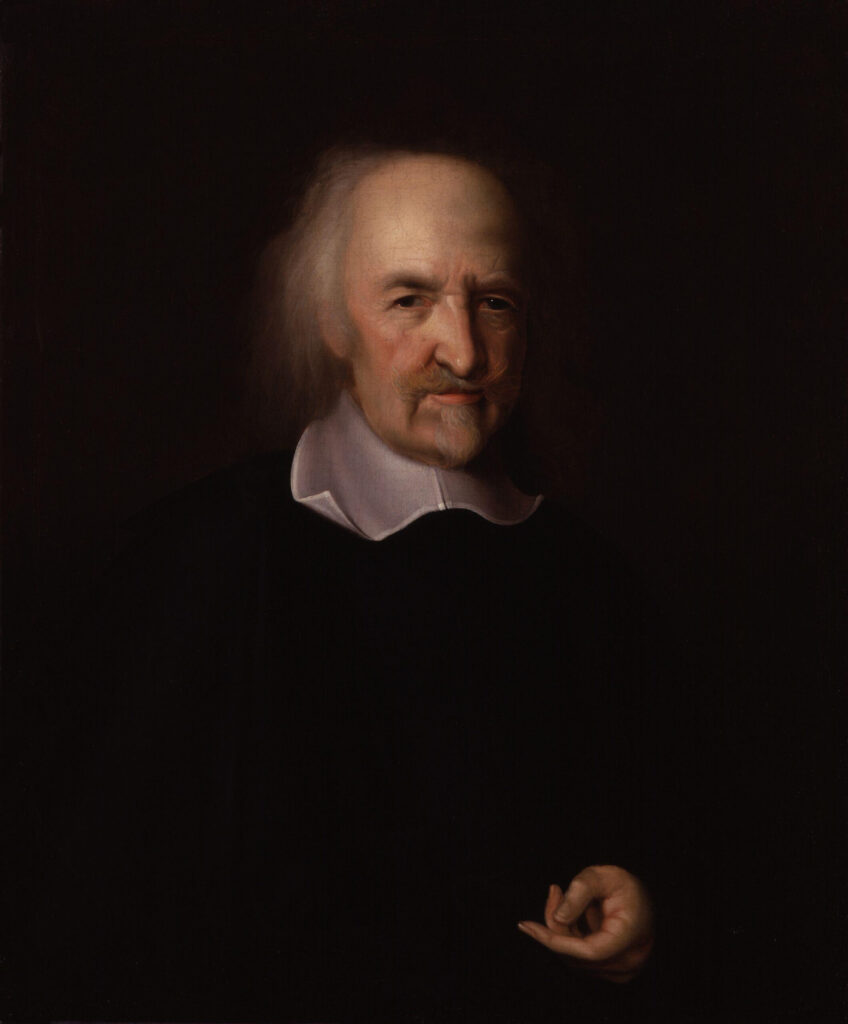

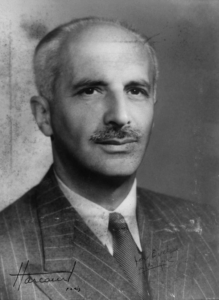

Thomas Hobbes was a philosopher and historian who published extensively on a vast range of subjects. Like others of his time, Hobbes’ religious scepticism had to be cloaked in wider expressions of orthodox belief to avoid the danger of persecution, but he was nevertheless the target of a 1666 parliamentary committee instructed to investigate his supposed atheism. Hobbes’ explorations of the natural causes of religion, and the extent (or lack) of his own religious belief, have been the subject of centuries of debate, but his suggestions about the psychological basis for superstition are a significant part of a freethinking tradition which paved the way for modern humanism.

And they that make little, or no inquiry into the natural causes of things, yet from the fear that proceeds from the ignorance itself… are inclined to suppose, and feign unto themselves, several kinds of powers invisible; and to stand in awe of their own imaginations; and in time of distress to invoke them; as also in the time of an unexpected good success, to give them thanks; making the creatures of their own fancy, their gods.

Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes (1651)

Hobbes was born on 5 April 1588 in Malmesbury, Wiltshire, the son of a disgraced clergyman, who was forced to flee the town for assaulting another vicar. Hobbes studied at Magdalene College, Oxford, and graduated in 1608. He then went to work as a tutor to William Cavendish (later the earl of Devonshire), giving him access to a rich library and a host of intellectual connections. He continued to work in various capacities for the wealthy Cavendish family for much of his adult life.

Prior to the publication of his first notable philosophical works in the 1640s, Hobbes published a translation of Athenian historian Thucydides, and travelled in Europe. A royalist, he was also associated with the controversies which gave rise to the Civil War: contributing to discussion over the extent and use of royal power. Hobbes fled to Paris in 1640, where he remained for a decade, working on what would become parts of his ‘great trilogy’: De Cive (1642), De Corpore (1655), and De Homine (1658).

Hobbes’ Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil was published in 1651, cementing his legacy as a leading political philosopher and, with its controversial sections on religion, leading Hobbes to fear prosecution for heresy. Leviathan was an early, and influential, examination of the ‘social contract’ idea, but as well as examining why man might give up certain freedoms in society, it also explored the origins of a religious impulse in humankind. Hobbes noted that religion was peculiar to humans, as was curiosity ‘in the search of the causes of their own good and evil fortune’. He proposed three reasons for the creation of a god and religion: ignorance, anxiety, and curiosity. Hobbes explained:

Ignorance of natural causes, disposeth a man to credulity, so as to believe many times impossibilities: for such know nothing to the contrary, but that they may be true; being unable to detect the impossibility. And credulity, because men like to be hearkened unto in company, disposeth them to lying: so that ignorance itself without malice, is able to make a man both to believe lies, and to tell them; and sometimes also to invent them.’

Anxiety for the future time, disposeth men to inquire into the causes of things: because the knowledge of them, maketh men the better able to order to the present to their best advantage.’

Curiosity, or love of the knowledge of causes, draws a man from the consideration of the effect, to seek the cause; and again, the cause of that cause; till of necessity he must come to this thought at last, that there is some cause, whereon there is no former cause, but is eternal; which is it men call God.

J.C.A. Gaskin argues that given the dangers of heretical opinion in 17th century England:

Hobbes is equivocal. His accounts of the natural causes of religion and of the language we can use about God sound (and I would contend really were) directly calculated to make religious belief uncomfortable. But he could have denied and for his own safety would have had to deny this objective.

Deniable or not, Leviathan was the target of much suspicion and criticism, during and after Hobbes’ lifetime. Its perceived anti-Catholicism led him to flee France and return to London, and his anxiety increased with 1662’s Licensing of the Press Act, which banned the print, sale, or import of any:

heretical seditious schismatical or offensive Bookes or Pamphlets wherein any Doctrine or Opinion shall be asserted or maintained which is contrary to Christian Faith or the Doctrine or Discipline of the Church of England or which shall or may tend or be to the scandall of Religion or the Church or the Government…

Hobbes biographer, John Aubrey, recorded that ‘some of the bishops made a motion to have the good old gentlemen burnt for a heretic.’ In 1666 a House of Commons committee was convened to examine texts of a blasphemous nature, with Leviathan mentioned specifically, but despite all this, Hobbes managed to live a long, largely healthy, life. He died on 4 December 1679 at Hardwick Hall.

Hobbes was acknowledged during his lifetime as a remarkable thinker, and exerted significant influence on those Enlightenment philosophers inspired by his critical examination of religion and power. His ideas, political and theological, continued (and continue) to be evoked and discussed by generations of thinkers, even though his apparent support for an autocratic ruler presents a challenge to many. In a history of the development of humanist thought, Hobbes’ reasoned scepticism, and eloquent exploration of the natural ‘causes’ of religion, secure his place.

The old teaching was that we must worship not truth, beauty and goodness, but their source, and that their source […]

Theodore Besterman… was one of the most remarkable of the long line of remarkable people who have given their support […]

With all the pretensions of spiritualists… No great truth containing a benefit to humanity has ever reached us; no addition […]

Conway Hall has effected a transformation. From the day of its opening the life of the Society has been full […]