…the smallest experience is sufficient to convince that it is more pleasing, to be at peace than at enmity with one’s fellow creatures, and… that superior pleasure is derivable from doing that which is agreeable to the best interests of society rather than the contrary. This appears to me to be a practical religion, based on common sense and the best interests of mankind, to combine all the advantages of all other religions, with none of their mystery or faults.

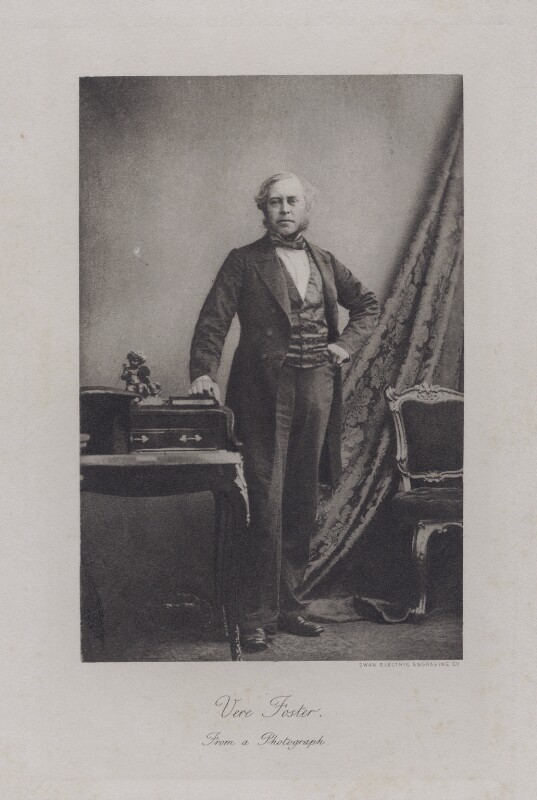

Vere Foster, draft of a letter, 1850, quoted in Vere Foster, 1819-1900: an Irish benefactor by Mary McNeill (1971)

Vere Henry Louis Foster was an educationist, philanthropist, and humanist, who worked devotedly to improve the situation of the Irish poor. His efforts, wrote Desmond McCabe, were ‘always characterised by vibrant humanity and tender humour’, and his own life lived ‘with extreme frugality’ but ‘uncalculating generosity’. In 1868, Foster helped to establish the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation (INTO), having personally worked for the improvement of Irish education since the 1850s.

Though born in Copenhagen to British parents, Foster’s experiences in Ireland, according to Northern Irish humanist and writer John D. Stewart, confirmed the humanism he had expressed from an early age, becoming his ‘lifetime creed’. ‘Since he alone could work right up the middle of Ireland’s dreary divide,’ suggested Stewart in 1971, ‘he achieved more social reform and betterment than any Christian Irish man before or after him’.

The biography reprinted below was first published in October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by McCabe, Desmond

Foster, Vere Henry Louis (1819–1900), philanthropist and first president of the INTO, was born 26 April 1819 in Copenhagen, Denmark, third son of Augustus Foster (d. 1847), diplomat and non-resident Irish landowner, and Albinia Jane (d. 1867), daughter of George Vere Hobart. His paternal grandmother was the unconventional society hostess and duchess of Devonshire, Elizabeth Hervey (d. 1824), and his paternal great-grandfather was the quixotic Frederick Hervey (qv), earl of Bristol and bishop of Derry 1769–1803. Schooled at home until the age of 11, he attended Eton (1830–34), and took private classes in Turin (1834–8), before matriculating at Christ Church, Oxford (May 1838), where he dabbled in legal studies for two years without taking a qualification. A dreary spell as a government audit clerk followed (1840–42). Between October 1842 and late 1843 he served as unpaid assistant in the diplomatic entourage of Sir Henry Ellis (1777–1855) in Rio de Janeiro and elsewhere in Brazil. After a year touring the antiquities of the east Mediterranean with his favourite (and eldest) brother, Frederick (d. 1857), he worked as unpaid attaché to Charles Ouseley in Buenos Aires and Montevideo (1845–7), where he worried his father by evincing undiplomatic enthusiasm for the cause of liberation under Garibaldi and other patriots. His superiors saw little room for radical feeling in the Foreign Office and passed him over for duties, paid or unpaid, once Ouseley was instructed to wind up his consulate in June 1847. Coming back with a menagerie of exotic birds and animals for his family, he impressed them less as a rueful unfledged diplomat than as a powerfully unorthodox individual, now with a mysterious sense of mission. Tortured by religious doubt, his father committed suicide in August 1847. In the aftermath of his death Foster took his first trip to the family estates in Louth, where he tidied up outstanding arrangements made for the emigration of a tenant to the USA. An ample inheritance gave him space to ponder suitable directions for his moral energies.

Less introspective than his father, he came firmly to the conclusion that he should shed attachment to divine revelation and the established church, and ground his sense of fellow-feeling on ‘that most simple art of pleasing oneself… [as] it is more pleasing to be at peace than at enmity with one’s fellow creatures’. He was never bothered by the logical flaws in such modified utilitarianism, needing the barest intellectual framework for his pure outgoing kindness.

In April 1848 he and Frederick visited the famine-stricken south-west of Ireland, making the usual concerned enquiries at workhouses and schools. Thoughts of ‘taking a farm in the west . . . in the hope of making myself useful . . . [by] giving increased employment to the people’ (McNeill, 46) prompted him to enrol on a year-long course of agricultural training at the Glasnevin model farm in September 1849. His hearty disregard for the pretensions of class, and delight in every kind of manual labour, startled the school inspectorate. He supplemented his practical education with private reflections on the basis of a constructive religious philosophy, poring over the Old and New Testaments in an effort to disentangle tolerable from intolerable in the text. Less introspective than his father, he came firmly to the conclusion that he should shed attachment to divine revelation and the established church, and ground his sense of fellow-feeling on ‘that most simple art of pleasing oneself . . . [as] it is more pleasing to be at peace than at enmity with one’s fellow creatures’ (ibid., 57). He was never bothered by the logical flaws in such modified utilitarianism, needing the barest intellectual framework for his pure outgoing kindness. Before the school year was over he had taken his first steps in assisted emigration, having paid passage to the USA for some forty tenants on his brother’s estate. His characteristic urge was to comprehend in the most practical manner every conceivable aspect of an endeavour or transaction in which he became involved, and it was in this spirit that he took passage for New York, with a friend from Glasnevin, in the steerage of the Washington, the largest vessel then operating in the emigrant trade. His findings shocked him beyond measure. The captain skimped on rations for the 900 passengers unless bribed, encouraged acts of random violence on helpless passengers by the crew, and was indifferent to conditions of filth that caused numbers of children to die of dysentery. A suspicious first mate once knocked him flat on the deck with a blow in the face. Publishing an open letter in New York on the cruel illegalities practised on the emigrant vessels despite recent enactments, he was instrumental in getting the issue debated in parliament, where, in spite of the dissimulation of the Liverpool shipping interest, a select committee was established to inquire into the workings of the remodelled passenger acts. The outcome was an improved system of inspection set up in early 1852.

Foster personally implored emigrants to respect all without distinction of race, religion or colour.

In New York he explored the seedy habitations of impoverished emigrants and studied their needs. From February to October 1851, despite much sickness, he travelled by coach, foot, and boat through vast tracts of the USA to seek out information on the state of former Irish emigrants and the economic potential of different regions, assembling copious notes on wage-rates, prices, projected works, and attitudes, remarking indeed that anti-English prejudice had become ‘a kind of political religion’ among Irish-Americans (ibid., 75). Back in Dublin by December 1851, he published a broadsheet as guide for the poor emigrant, running off thousands of copies for distribution around the country. The project of assisted emigration had swept away his first idea of farming in the west. On the principle that poor young women were the most powerless members of Irish society, he established, principally with his own capital, the Irish Female Emigration Fund (1852), dedicated to all-embracing support for the emigrant, on condition that she make a contribution according to means and pass on the benefits of employment in the US to the rest of her family hoping to follow. He sent a thorough questionnaire to contacts in the US to monitor employment conditions and in September 1852 published a short pamphlet, circulated free of charge, containing revised information on prospects for the emigrant. The female emigrant was provided with the necessities of travel, and advised on honest accommodation and sources of employment. If at all possible, jobs in domestic service were provided for those interested. Foster personally implored emigrants to respect all without distinction of race, religion or colour. From 1850 to 1857 he went to the USA once or twice each year to update his data and expand his network of contacts. Though he was brimming with zest, there was little or no self-indulgence in these visits. In this period he paid the fares and other costs for 1,250 female emigrants and 2–300 men and boys. He typically accompanied bunches of emigrant girls from departure to destination in the cities and towns of the mid-west. By 1856 his personal fortune was considerably depleted and there was a growth of antagonism to the concept of assisted emigration as labourers’ wage-rates rose and farmers felt the pinch. Hot accusations that he was selling girls into prostitution in the New World, or corrupting their faith, inflamed press reports on the subject. Though he located numerous emigrants of whom this was alleged, took their portraits by daguerrotype, and on one occasion silently displayed their images, addresses, and recent history, with letters of confirmation, in Ardee, Co. Louth, he considered it best to shut down the fund by 1858, when he parcelled off his last group for some time.

Though he often enlisted the aid of philanthropic women’s groups in the USA to help with the final stages of the emigrant route, he had for years (to save expense) relied entirely on his own formidable energy to administer the organisation at home. Taking a cue from a suggestion by his recently deceased brother, he now bent his mind to developing the Irish primary school system. He planned at first to spend an inheritance from his brother in constructing first-rate schoolhouses throughout Co. Louth, counting on two-third grants from the board of national education for each building. It was swiftly borne in on him that none of the religious denominations would cooperate wholeheartedly with schools vested in the commissioners of national education. He then adjusted his aims to provide funds for the most needy schools inside or outside the national system, on condition that every school first make a nominal contribution to the refurbishment fund. Schools in the poorest districts were circularised, and he undertook intrepid walking tours of inspection. The local response was extraordinary, though it took a year or two before the board of national education overcame an incredulous suspicion. The effects of school repair were dramatic by the early 1860s. Wooden floors replaced clay everywhere, and seats for children and teacher were provided. In 1864 he came up with an ingenious method of instruction in penmanship, the foundation for clerical employment. He devised a model headline copybook, shaped to suit a child’s needs, in which samples of the finest script were printed above lines that were left blank for transcription by the student. The board of education was given the chance to approve the scheme. Some 50,000 copies were printed at his expense in early 1865 for sale at rates of one or two pence each, well within the means of smallholder and labourer. These simple schoolbooks revolutionised Irish primary education and remained as standard school manuals until the 1900s or later. Profits were religiously reinvested by him in the scheme.

Just as there was no shade of paternalism in his administration of assisted emigration, his success in the educational field derived greatly from a temperamental naivety and joy.

In 1870 he established an annual prize scheme in which children from all over the British empire competed in lettering, drawing, and painting. Just as there was no shade of paternalism in his administration of assisted emigration, his success in the educational field derived greatly from a temperamental naivety and joy. Concerned from the later 1850s at the shabby treatment of national teachers by local and national boards, he proved a force in the movement for redress in the 1860s and 1870s. He regularly brought the plight of teachers to official notice in the early 1860s. In late 1867 he helped found the Teachers Journal to publicise discontent and focus campaign activity in favour, above all, of getting security of employment and raising pitiful Irish salaries to English rates. He presided ‘with more than judicial impartiality’ (McNeill, 160) over the conference of national teachers in Dublin (December 1868) at which the Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO) was formed. He presided at congress each year until 1872, when a vociferous minority of delegates shouted him down for his conviction that advances in the school system should be financed by local rate rather than by imperial contribution.

During the early 1880s his programme of assisted female emigration was restored to operation during severe distress. Though nationalists were at best reserved towards the project (John Boyle O’Reilly (qv) editorialised in the Boston Pilot in 1881 against the idea, though he had himself written to Foster in 1874 for help towards his sister’s emigration) he was inundated with queries for aid. His endeavours were independent of the contemporary work of James Hack Tuke (qv). From 1880 to 1887 he assisted over 20,000 girls to leave for work in the USA at a probable minimum cost to his personal capital of £55,000. During his entire life in Ireland he had lived with extreme frugality and donated funds with uncalculating generosity. By 1890 his means from all sources were exhausted and he lodged alone in a cheap attic room in Belfast, whither he had moved in 1868. In 1898 he completed an account of his grandmother’s unique friendship with the wife of her lover. Late that year he was spotted sitting in Donegall Place, holding out a plate to receive donations for the Royal Hospital, a favourite charity since the 1870s. A summary of his prodigious labours runs the risk of creating a distorted image of the dour Victorian philanthropic zealot, but Foster’s work was always characterised by vibrant humanity and tender humour. He died, unmarried, on 21 December 1900 at 115 Great Victoria St., Belfast. His papers are held in PRONI.

Report of the select committee on the passenger acts, HC 1851 (632), xix; Vere Foster, Origin and history of Vere Foster’s writing and drawing copy-books (1882); DNB; S. Shannon Millin, Sidelights on Belfast history (1932); INTO, Short biographical study of Vere Foster (1956); Oliver MacDonagh, A pattern of government growth, 1800–60: the passenger acts and their enforcement (1961); T. J. O’Connell, History of the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation, 1868–1968 (1968?); Mary McNeill, Vere Foster, 1819–1900: an Irish benefactor (1971); DIH; Report of the deputy-keeper (PRONI) 1983; Art Byrne and Sean McMahon, Great northeners (1991); Alison Jordan, Who cared? Charity in Victorian and Edwardian Belfast (1996?); Sarah Ward-Perkins, Select guide to trade union records in Dublin (1996), 85–7; Ruth-Ann Harris, ‘“Where the poor man is not crushed down to exalt the aristocrat”: Vere Foster’s programmes of assisted emigration in the aftermath of the Irish famine’, Patrick O’Sullivan (ed.), The Irish world wide: history, heritage, identity, vol. 6: the meaning of the famine (1997), 172–94

Vere Foster | Dictionary of National Biography (1901)

Vere Henry Louis Foster | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Vere Foster | Dictionary of Ulster Biography

Vere Foster’s Irish Female Emigration Fund | History Hub

‘Vere Foster – One of the greatest men you’ve never heard of’ | Belfast Entries

They weren’t just trying to sell something to parents, they were helping them to understand how to play with and […]

Emancipation from every kind of bondage is my principle. I go for the recognition of human rights, without distinction of […]

Rationalism is… primarily a mental attitude, not a creed or a definite body of negative conclusions. No uniformity of opinions […]

It is in service to others, it is as members of the community, that our existence lies. Hermann Bondi, Humanism […]