The one thing in which I am interested wholly and completely is the getting to know something about human society and working at some part of its machinery… the question of under what conditions it is possible and worth while for men as a whole to live.

William Beveridge in a letter to his mother, 25 January 1903, printed in Power and Influence: an autobiography (1955)

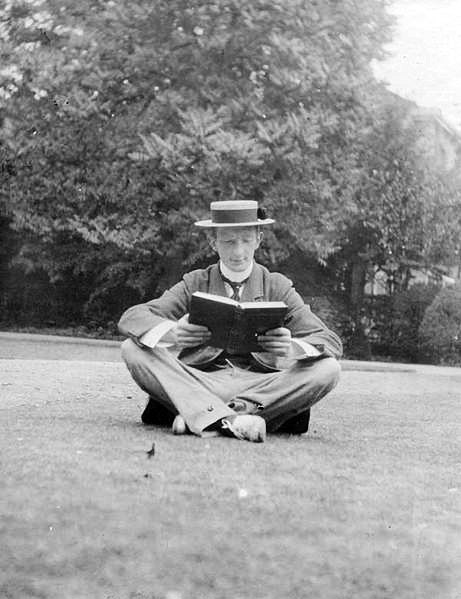

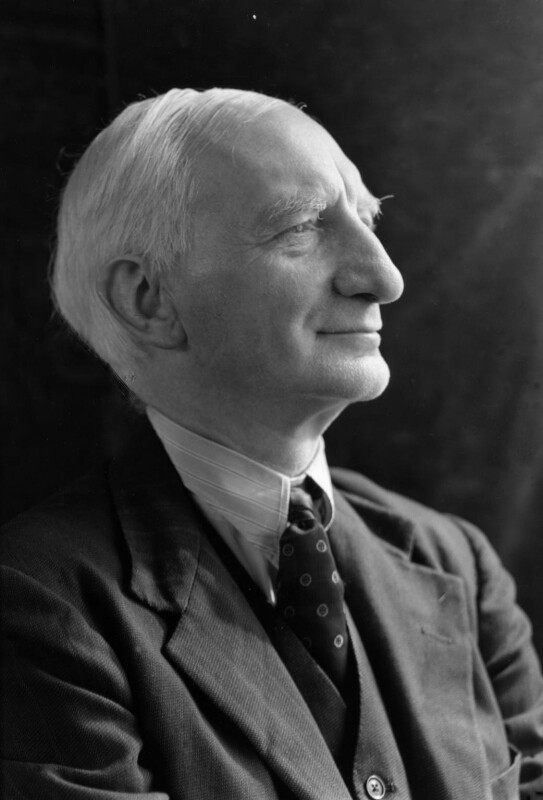

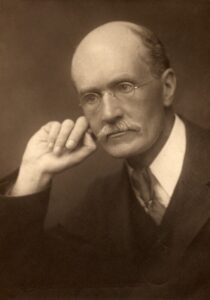

William Beveridge was an economist and social reformer, whose landmark ‘Beveridge Report’ paved the way for the welfare state. This 1942 report, Social Insurance and Allied Services, recommended state-organised care for all citizens from birth to death in the aftermath of the Second World War, ultimately giving rise to the creation of the National Health Service. Beveridge was also instrumental in forming the Academic Assistance Council (later the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning) in 1933, to provide assistance to academic refugees from Nazi Germany.

Described by his biographer Jose Harris as a ‘thoroughgoing materialist agnostic’, Beveridge was motivated not by any religious belief, but by a strong social conscience and a formidable desire to bring about genuine change.

For me, partly because I was made so by my father and mother, partly because I was told so by Aristotle thirty-five years ago, happiness is doing something and a holiday is doing something else.

William Beveridge, address on ‘My Utopia‘ to the Cosmopolitan Club of LSE., 23 October 1934

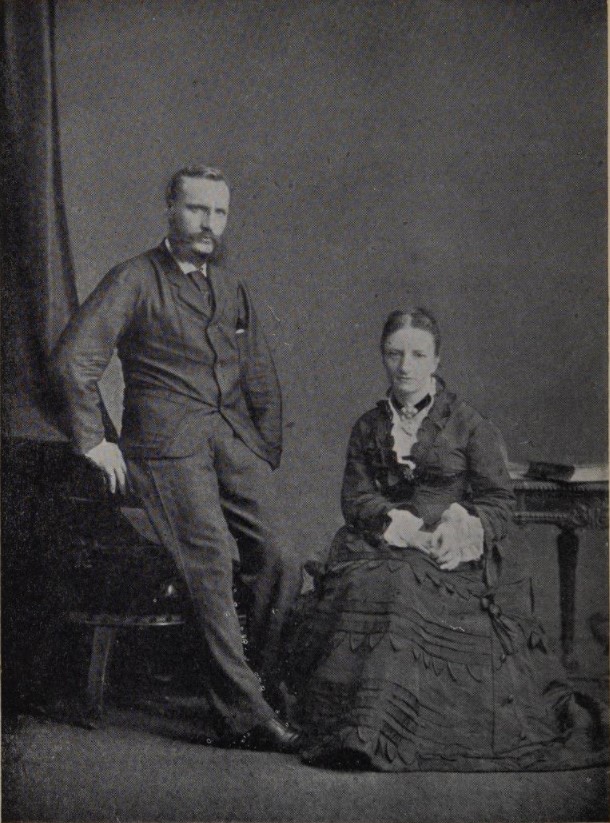

William Henry Beveridge was born in Rangpur, Bengal in 1879, the son of civil servant and supporter of Indian nationalism Henry Beveridge, and orientalist Annette Beveridge (née Akroyd). Of his parents, he would later write: ‘They were both so well worth knowing that I should like them to be known to many’. His father, Beveridge wrote, abandoned the Presbyterianism of his upbringing and:

became an agnostic, not denying religion, but denying his own capacity to know whether there was a God or a future life. And he took his agnosticism seriously, declined to do or say anything that would rank him as a Christian, declined to go to church to be married, declined in due course to have his children brought up as Christians or as members of any church.

Henry Beveridge himself wrote:

I cannot say that want of religion has seriously saddened me… Virtue and morality are independent of revealed religion… The great thing is to be just and fear not, to use John Bright’s favourite phrase. A love of truth in thought word and deed is looked upon by your mother and myself as the main quality to be desired.

Henry Beveridge in ‘Memorandum on his Religious Opinions written for him by his children’, quoted in India Called Them by William Beveridge (1947)

Beveridge described his father as ‘a model of quixotic devotion to any cause in which he believed’, and at nineteen expressed his own belief:

that no man can do really progressive work who has not one idea carried to excess… The man must have one great ideal to aim at, to a certain extent excluding all else, and his convictions must be very strong.

Educated at the University of Oxford, where he excelled, Beveridge initially seemed destined for a successful career in either academia or legal practice. He was, however, driven by an urge to apply his intellect to social problems. Writing to his mother in 1903 to announce his decision to give up law, Beveridge stated his conclusion that as a barrister:

One never gets the sense of working either with or for other people and one or other of these things I cannot do without.

In pursuit of this kind of fulfilment, Beveridge accepted the role of sub-warden at East London’s Toynbee Hall, the originator of a growing collection of ‘university settlements’, to which many figures in the early organised humanist movement were drawn. Here, university graduates lived alongside working people, with the intention that each group would learn from the other. Beveridge’s first-hand experiences of seeing poverty and squalor in the East End of London motivated him to do something to promote social justice and eradicate hardship – from insecure jobs to malnutrition. He was inspired too by the writings of T.H. Huxley and the positivism of Auguste Comte. Huxley had, in 1854, imagined extending the principles of biology (observation, experiment, proposition, deduction, and verification) to encompass human life and society, anticipating the ‘Science of Society or Sociology’ which would go on to animate Beveridge’s life and work.

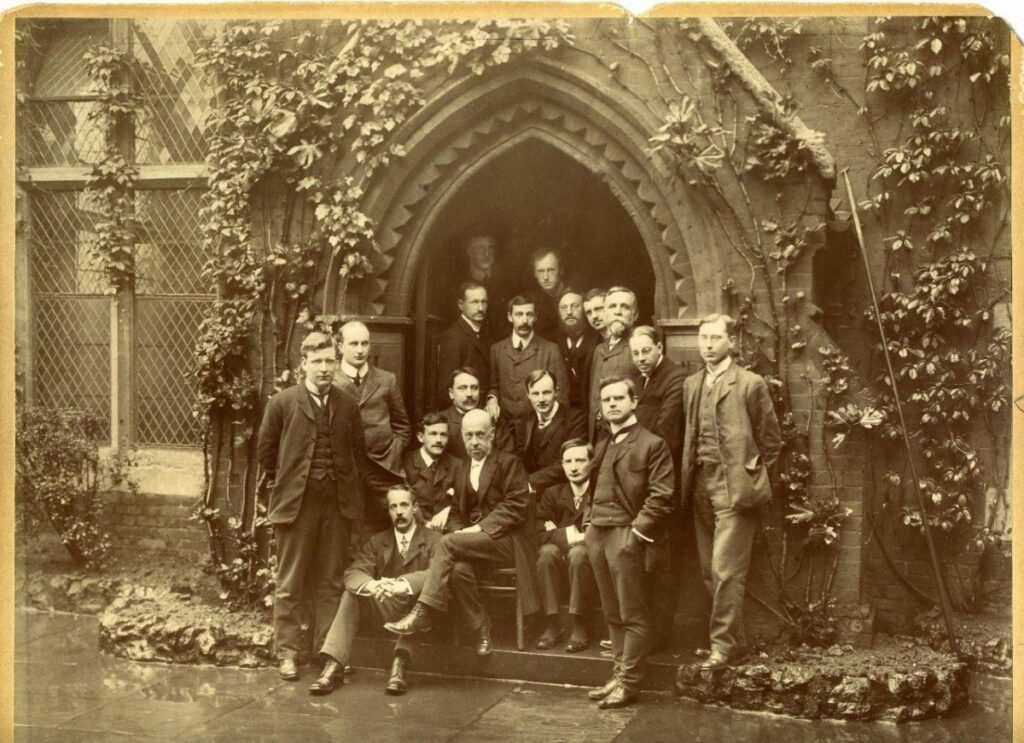

On leaving Toynbee Hall in 1905, Beveridge worked as a journalist, editor, and civil servant. During the First World War, he was employed in the Ministry of Munitions, the Board of Trade, and the Ministry of Food, where he was responsible for rationing and food prices. In early 1919, Beveridge was appointed permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Food, but resigned in June to become Director of the London School of Economics, then still a small college. Over the following two decades, he engineered and oversaw its major expansion, raising funds and recruiting leading scholars. In this role, he helped a number of academic refugees fleeing Nazi Germany in the early 1930s, founding the Academic Assistance Council (later the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning) to provide support. Beveridge remained at LSE until 1937, when he left to become Master of University College, Oxford.

Despite a defining role at LSE, it remains the 1942 ‘Beveridge Report’, produced as Chair of an Inter-departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, for which William Beveridge is best remembered today. In the midst of the Second World War, he saw an opportunity to dramatically rethink social provision in the aftermath of global conflict:

Now, when the war is abolishing landmarks of every kind, is the opportunity for using experience in a clear field. A revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching.

The report, begun in 1941 and published in 1942, was officially titled Social Insurance and Allied Services. It contained proposals for widespread reforms to the system of social welfare, addressing what Beveridge identified as five ‘giant evils’: Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness. He recommended that the government find ways of fighting these evils before Britain could enjoy true social prosperity following the war.

There is no need to spend words today in emphasizing the urgency or the difficulty of the task that faces the British people and their Allies. Only by surviving victoriously in the present struggle can they enable freedom and happiness and kindliness to survive in the world. Only by obtaining from every citizen his maximum of effort, concentrated upon the purposes of war, can they hope for early victory. This does not alter three facts: that the purpose of victory is to live into a better world than the old world; that each individual citizen is more likely to concentrate upon his war effort if he feels that his Government will be ready in time with plans for that better world; that, if these plans are to be ready in time, they must be made now.

The report was overwhelmingly popular with the public and paved the way for the post-war reforms in the United Kingdom known as the welfare state, put in place by the Labour government elected in 1945. This included the expansion of National Insurance and the creation of a National Health Service to enable free medical treatment for all. A national system of benefits was also introduced to provide ‘social security’ for the UK population so that along with the NHS, they would be protected from the cradle to the grave.

In 1944, Beveridge was elected Liberal MP for Berwick upon Tweed, and in 1946 entered the House of Lords as a Liberal peer. Over the following years, he published India Called Them (1947), Voluntary Action (1948), Power and Influence (1953), and worked on his compendious Prices and Wages in England from the Twelfth to the Nineteenth Century. He died at home in Oxford on 16 March 1963, and was buried in Thockrington, Northumberland.

The proposals of this Report… are a sign of the belief that the object of government in peace and in war is not the glory of rulers or of races, but the happiness of the common man.

William Beveridge, Social Insurance And Allied Services (1942)

Beveridge’s 1942 report was founded on the belief that State support could, and should, enable citizens to live fulfilling, meaningful lives: ‘showing that security can be combined with freedom and enterprise and responsibility of the individual for his own life’. In an essay published the following year, Beveridge stated his belief that although ‘not brought up in any religious faith’, or a ‘member of any religious community’, he firmly believed that:

there should be something in the daily life of every man and woman which he or she does for no personal reward or gain, does ever more and more consciously as a mark of the brotherhood and sisterhood of all mankind.

‘The Five Christian Standards’ in The pillars of security, and other war-time essays and addresses (1943)

Echoing his father’s assertion that ‘virtue and morality are independent of revealed religion,’ Beveridge advocated a selflessness and social concern derived from the purely human. His sense of influence and immortality was similarly humanist, believing that it is ‘in trying to do better for the next generation than we have done for ourselves, we get our second chance.’

William Beveridge: A Biography by Jose Harris (1997)

William Beveridge | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

‘Who was William Beveridge?’ | Fabian Society

William Beveridge papers | LSE Archives

But in the more civilised communities, as in ancient Greece, there has always been a minority who, through some speculative […]

Mackenzie Hall is a community space in the village of Brockweir, Gloucestershire, given by Millicent Mackenzie in memory of her […]

From the outset IAS aimed to have an open approach to prospective adopters irrespective of their race, religion and creed, […]

I believe in the absolute equality of the sexes, and I think they [women] should be in the enjoyment of […]