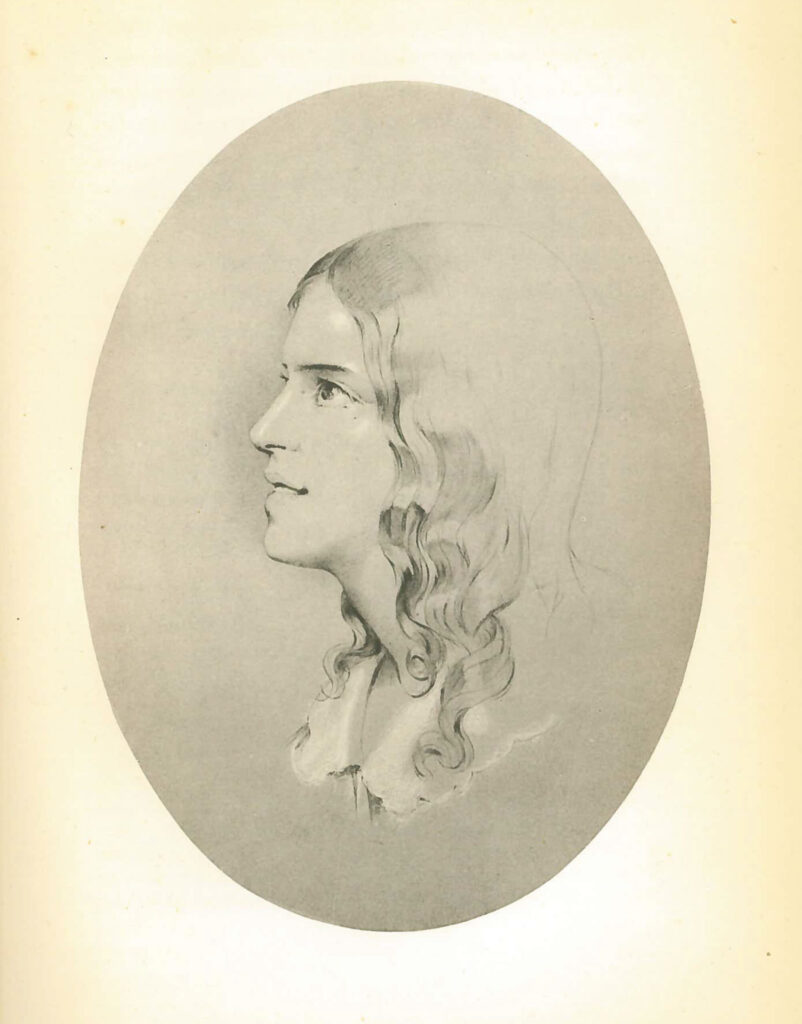

William Johnson Fox was an orator, writer, politician, and first minister of South Place Chapel (now Conway Hall) from 1824 – 1852. Dedicated to the inclusiveness, and community purpose, of congregation, Fox was a vital figure in the development of South Place and its move towards humanism, also playing a key role in the early careers of writers such as Alfred Tennyson and Harriet Martineau.

Born in Suffolk, William Johnson Fox was the oldest son of a strictly Calvinist artisan: at various times a farmer, weaver, shop-keeper, and teacher. Moving to Norwich at three, Fox was educated at a school adjoining St George’s Independent Chapel before beginning work as a weaver. Himself a voracious reader and auto-didact, Fox’s mother would also read aloud to her son while he worked, imbuing him with the love of literature that would animate his life.

Fox moved from weaving to working for six years in a bank, before leaving Norwich for Homerton in 1806 to train as dissenting minister. Initially in charge of a congregation at Fareham, Fox began to question aspects of his faith, writing to a friend in 1810:

My future lot becomes every day more doubtful… My own plan at present is this – to fulfil my twelve months’ engagement, to advance my sentiments boldly – explicitly – firmly, and at the end of the time to remain with them, should they wish it – only, on certain conditions, such as throwing open the doors of church fellowship to heretics, etc.

Moncure Conway describes how for Fox, ‘the dogmas of Trinity and original sin were given up in 1810; pre-existence of Christ and Atonement were abandoned a year later; and the eternity of hell yielded in 1812.’ He notes too that Fox’s ideal at Fareham, ‘to form a congregation… with Virtue and not Faith for the bond of union,’ anticipated the Ethical Culture Movement 80 years ahead of its inception in England. Appropriately, in 1816, he succeeded William Vidler as the minister of Parliament Court Chapel, which he opened for evening lectures on ‘great public and social problems, Church and State, War, Philanthropy, Population, Human Perfectibility.’ For this, Conway called Fox ‘the great human revivalist… bringing his Society into relation with the general cause of humanity’.

Indeed, R. K. Webb describes Fox as ‘an aggressive and eloquent champion of the extension of full civil rights to dissenters and of the broadest interpretation of toleration’. Following the 1819 arrest of Richard Carlile for publishing Paine’s Age of Reason, Fox delivered a sermon on ‘The Duties of Christians towards Deists,’ in which he warned against any prosecutions on account of belief – or its absence. He argued that:

There is no medium in principle between the liberty of all and the tyranny of a particular sect. Christians, you kindle a flame in which yourselves may perish.

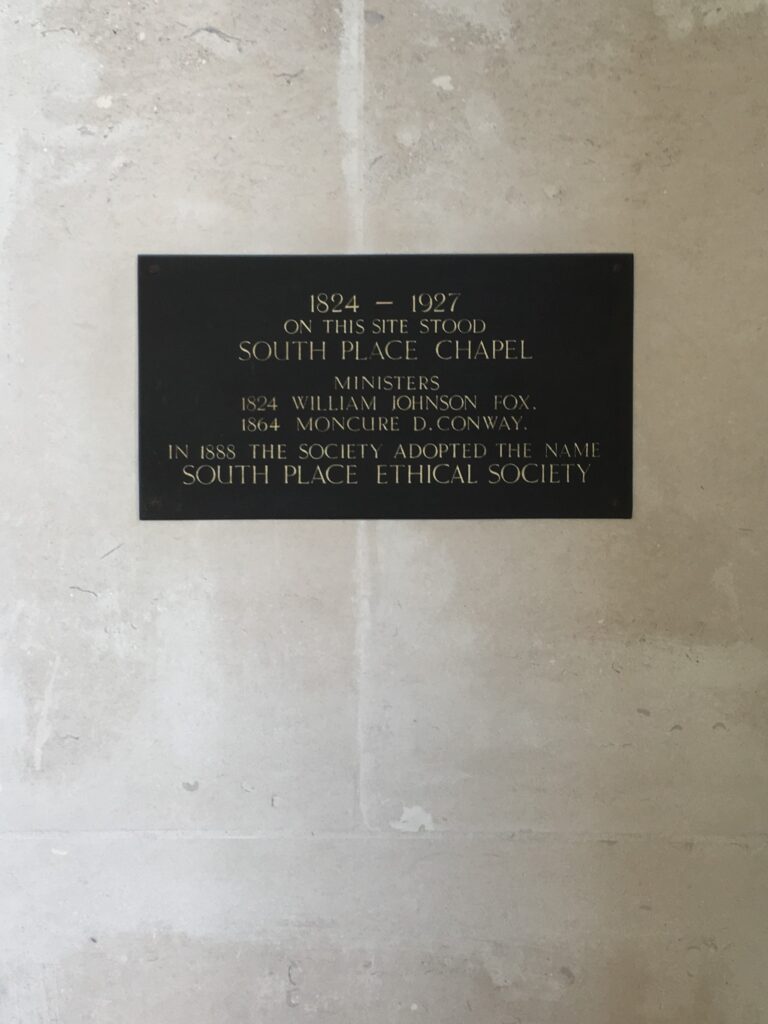

Under Fox’s leadership, the congregation moved in 1824 to the newly built South Place Chapel. Laying the first stone in the previous year, Fox proclaimed:

All of us must soon pass away, and other generations shall succeed us here; but may the same spirit blend together all the successive generations… animating them with the like ardour for truth and righteousness; uniting them in love and good works; surrounding them with a bright atmosphere of usefulness on earth.

At its opening, Fox invoked those ‘who have raised the standard of religious freedom, and fought its battles… not only for those who were like-minded with themselves, but on behalf of all’. In 1825, Fox was central to the formation of the British and Foreign Unitarian Association and acted as its first foreign secretary.

Fox was a gifted orator, and much praised by those who heard him speak. He turned his power of speech to both religious and political subjects, with listeners comparing his delivery to musical composition. In his a Conway Memorial Lecture in 1924, Professor Graham Wallas noted that:

those thoughts are most effective which are simple in themselves, but whose varied expression produces, like the thought behind a Beethoven sonata, a feeling of infinite significance. Such are the thoughts which again and again inspire Fox’s eloquence—the purposes of Nature, the principle of freedom, the hopes of reason and progress, the solidarity of mankind, the truth which underlies all religions.

In 1831 Fox purchased the Unitarian Monthly Repository, a journal he had edited – and expanded the scope of – since 1827. He transformed the Repository from a denominational to a mainly literary magazine, supporting the early careers of Harriet Martineau, Alfred Tennyson, and Robert Browning. Martineau said of Fox that he was: ‘the occasion, and in great measure the cause, of the greatest intellectual progress I ever made before thirty.’ Browning described him as his ‘literary father’.

It was in the Repository too that, in 1834, Fox advocated for divorce on the grounds of incompatibility of temperament, which saw the other five Metropolitan Unitarian ministers break with him. Following complaints from his wife to members of the congregation (principally relating to Fox’s close relationship with composer and ward Eliza Flower), Fox had earlier in the year been remonstrated and tendered his resignation. This was, however, withdrawn at the request of a majority of the congregation. 43 of 156 seat-holders left after the decision. The same year at South Place saw a widened sweep of sermon subjects, abdication of the title of ‘reverend’ and the end of administering the sacraments.

From 1843-6, Fox was a paid writer and lecturer for the Anti-Corn Law League and for two years from 1844, also spoke weekly at the National Hall of the Working Man’s Association in Holborn, speaking in support of Chartism, public education, free trade, pacifism, and the enfranchisement of women. Of the latter, it was said that

Fox’s intimate friendship with John Stuart Mill and Mrs. Taylor, and the circumstances of his own life, gave his thought a certain fullness and modernity of content.

From 1847-62, with breaks, Fox represented Oldham as a Liberal MP.

Fox died in London on 3 June 1864 and was buried in Brompton Cemetery. His memorial service at South Place was led by Moncure Conway.

The trust-deed for the South Place Chapel, enrolled under Fox in 1825, established the freedom and flexibility that would allow it to become the South Place Ethical Society under the later leadership of Stanton Coit. The deed contained the provision that the congregation would be a place for religious worship

at such times, according to such forms, and under such regulations as are now adopted, or shall from time to time be adopted by the said Society.

For Conway this proved ‘how deliberately, at a time when Deists were in prison and Unitarians in peril, they planted the taproot of their tree in liberty.’ This openness to adapt to the beliefs of the congregation and its leader, as well as to the needs of society itself, paved the way for the humanism heralded by its becoming an ethical society in 1888.

‘Being Rational About Being Gay’ was a talk given by activist Antony Grey (Anthony Edgar Gartside Wright) for the Gay […]

Lift the heart to high endeavour! Fire the thought and nerve the will! Though the bonds be hard to sever, […]

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]

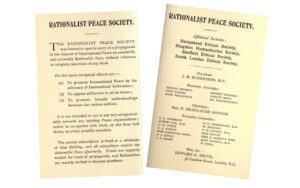

…a slowly growing public opinion in favour of arbitration as the alternative to war… is not in consequence of any […]