William of Ockham was the fourteenth century’s most influential philosopher: a key thinker of the Middle Ages and an early proponent of the separation of Church and state. Understood in the context of Medieval philosophy (practised by theologians, with a central belief in the divine revelation of knowledge), William of Ockham stands as an example of questioning and scepticism amid centuries of strict religiosity, rather than of outright unbelief.

William of Ockham was born at Ockham, near Guildford in Surrey. He attended Oxford University, where his lectures made a significant impression on the students – and faculty – of theology. In 1323, when Ockham had completed his BA, the university’s chancellor John Lutterall went to the papal court to prevent him from gaining his teaching licence, accusing Ockham of holding ‘dangerous and heretical doctrines’. Because of this interruption to his career, leaving Ockham an ‘inceptor’ without a teaching licence, he became infamous as the ‘venerable inceptor’.

The following year, Ockham was summoned to the papal court at Avignon, France, to answer to the charges against him. He remained there for four years, awaiting the outcome and working on his own philosophy and writings. Becoming embroiled in a dispute over doctrine, and adopting a position contrary to that of the Pope, John XXII, Ockham fled France in 1328 and was excommunicated. From Munich over the following years, he continued to write treatises against the papacy. His belief in the centrality of free will, and in a God who gave this to human beings, led Ockham to dispute any notion that the Pope should be able to use his power to deprive others of their freedoms, ‘lest he should turn the law of the Gospels into a law of slavery.’ These treatises have been described as forming a ‘groundbreaking defense of individual rights, separation of church and state, and freedom of speech.’

Ockham himself remained a devout Christian, and his writings show an evident faith in the concept of divine truth and revelation. However, because of his carefully constructed criticisms of alleged theological proofs, he has been received by some as an unbeliever. What Ockham rejected was the possibility of ‘proving’ what cannot be proved, i.e. the existence of God, a concept taken up by many future freethinkers and humanists. He argued against the idea that theology was a science, believing instead that religious belief was a matter of faith alone.

William of Ockham died in 1347, but his ideas (and misinterpretations of them) remained controversial throughout the middle ages.

Ockham’s ‘heretical’ ideas sit firmly in a tradition of religious dissent, and the centuries-long suppression of teachings which challenged the Church’s power. His teachings and reputation attracted followers and critics alike, during his lifetime and for hundreds of years hence; later figures who acknowledged a debt to Ockham included major figures of the Reformation, like Martin Luther. In this sense, Ockham’s name remained synonymous with the questioning of established beliefs and corrupt power structures which, even when placed within the context of his own religious faith, remains of significance to humanists today, and to the tradition of scepticism from which it developed.

Today, Ockham is best remembered for ‘Ockham’s razor’ – his principle that entia non sunt multiplicanda sine necessitate (one should not multiply entities beyond necessity). This method of evaluating competing hypotheses gives preference to simplicity. It has come to be defined by many as meaning that the simplest explanation is often the correct one.

Girton College at the University of Cambridge has educated and employed a host of remarkable humanists and freethinkers, many of […]

Ethics really ought to have something to do with life. Ethics ought to tell you how to be good or […]

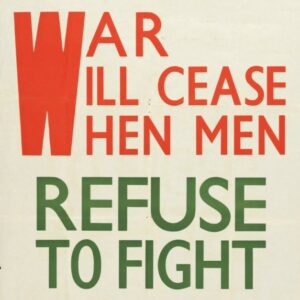

We are living in critical days. It is not enough to desire peace or to talk peace. We must make […]

The difference and variety of our human family more and more seems to me to be a wise provision that […]