But in the more civilised communities, as in ancient Greece, there has always been a minority who, through some speculative urge in their own minds or perhaps through the circumstances of their own lives, have felt convinced that the traditional frame of dogmas current about them did not represent the exclusive truth, the necessary truth, or even any exact truth at all about the ultimate mysteries, and have tried to keep their sense of the duty of man towards his neighbour and his own highest powers clear of the confusing and sometimes perverting mythology on which it is traditionally said to be based. Its real basis is the rock of human experience.

Stoic, Christian and Humanist (1940)

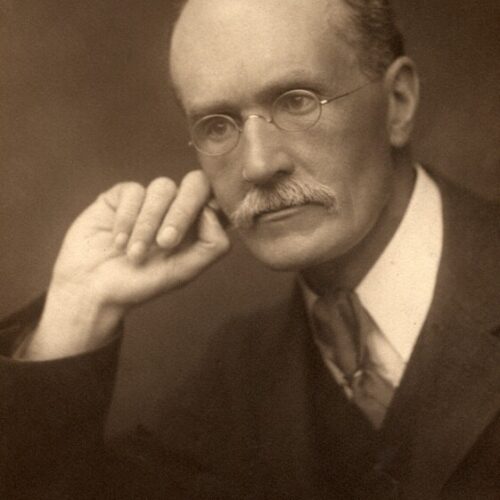

Gilbert Murray was a classical scholar, peace activist, and prominent humanist, who served as president of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) 1929-30. He was also present at the inaugural World Humanist Congress in 1952, from which was formed Humanists International. Murray was a humanist in both the Renaissance and contemporary definitions of the word: a devotee of the classical humanities, and of rationalism, kindness, and cooperation.

Gilbert Aimé Murray was born in Sydney, Australia on 2 January 1866. Four years after the death of his father, he came with his mother to England, and was educated in Brighton and London. He went up to Oxford with a scholarship in 1884, where he excelled. He married Rosalind Howard in 1889, the ceremony conducted by Benjamin Jowett, a close collaborator with T.H. Green in the efforts to widen entry to the University of Oxford.

In the same year as his marriage, Murray had been made chair of Greek at the University of Glasgow, where he excelled despite large class sizes, and his subject being one of compulsory study. However, Murray’s lifelong devotion to the language and values of this ancient study was clear, announcing in his first lecture that:

Greece, not Greek, is the real subject of our study. There is more in Hellenism than a language, although that language may be the liveliest and richest ever spoken by man.

Six decades later, Murray would say:

Still, there has never been a day, I suppose, when I have failed to give thought both to the work for peace and for Hellenism. The one is a matter of life and death for all of us, the other of maintaining amid all the dust of modern industrial life our love and appreciation for the eternal values.

Unfinished Battle, BBC 1 January 1956

Murray remained at Glasgow until 1899, when he resigned partly on grounds of ill health. His three volume translation of Euripides for the Oxford Classical Text series appeared in 1901, 1904, and 1909, and was reprinted several times. These and other classical translations won Murray wide acclaim, as did his skill in reading them aloud. His obituary in The Times would describe him as ‘at home in the human and sceptical Euripides’. Murray took up a fellowship at New College, Oxford in 1905, later becoming regius professor of Greek. While there, he spearheaded the campaign for abolishing the compulsory study of the subject, only accomplished in 1920. He was president of Somerville College 1916-1919, and vice president of Oxford University Liberal Club for many years.

Throughout the First World War and afterwards, Murray was actively involved in efforts towards peace. He worked to assist those imprisoned as conscientious objectors (among them, Bertrand Russell), and towards international cooperation within the League of Nations Society, League of Nations Union, and the League of Nations from its inception in 1920. During the 1930s, Murray was involved in the relocation and employment of refugee scholars from Germany, and collaborated with William Beveridge in forming the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (1934). Through all of this, wrote Russell, he ‘did everything that lay in his power to salvage civilization’.

Gilbert Murray died at his home in Oxford on 20 May 1957. He was cremated, according to his wishes, and interred at Westminster Abbey. The Manchester Guardian hailed him as ‘the greatest humanist of [the] generation’.

Simple kindness, simple courage, simple honesty, unassailable integrity, genuine and therefore inspiring humility – one of these qualities is enough for any man. He had them all.

a correspondent, The Times 31 May 1957

Bertrand Russell described Murray as a ‘great and steadfast humanist’. As a scholar, he allied classical humanism with contemporary life, making the world of the ancient Greeks – as the Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature writes – ‘sensitively real to his contemporaries’. He sought to bring the poetry and wisdom of these classical works to a new audience, believing passionately in the ‘eternal values’ they revealed. In his decades of work in the spirit of international cooperation, he exemplified a belief in the capacity of humankind to improve itself on the grandest scale. In his defence of those who objected to fighting, he proved his devotion to the values of freedom and self-determination.

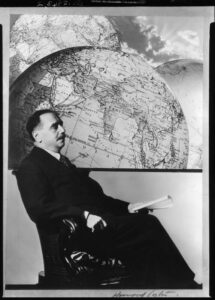

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]

We have the faculties for gaining knowledge; and Rationalism will always maintain that we are at liberty to use them […]

I have come to feel that the best proof of the subjection and degradation of my sex lies in the […]

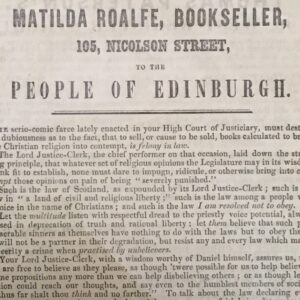

I will never voluntarily obey any law which is an outrage on human reason. Matilda Roalfe Matilda Roalfe was an […]