I have come to feel that the best proof of the subjection and degradation of my sex lies in the opinions often expressed by so-called Christian and pure women about other women. If their judgments were not perverted, if their wills were not broken, if their consciences were not asleep, and if their souls were not enslaved, they would not, they could not, hold their peace and let the havoc go on with women and children as it does.

Laura Morgan-Browne, Woman’s Herald (27 fEBRUARY 1892)

Like so many women drawn to the early humanist movement, Laura Morgan-Browne was a progressive thinker and a tireless activist, but has been little remembered in histories of the causes she fought for. Morgan-Browne and two of her children were founding members of the West London Ethical Society, which sought to advance social reform and moral ideals on ‘purely human’ grounds. She was also prominent in a number of groups with women’s suffrage at their heart, as well as in promoting rational dress, and progressive social reform.

We must reach the mass through the unit, it is the individual who helps to move the world.

Laura Morgan-Browne

Laura Elizabeth Morgan-Browne was born Laura Elizabeth Cooper in London on 15 June 1843, the daughter of John Cooper, a linen draper, and his wife Mary. She married William Morgan Brown [sic], patent agent and a decade her senior, on 25 February 1865. The couple had four children: Hubert (b. 1867), Hilda Kathleen (b. 1868), Lionel (b. 1870), and Mary Beatrice (b. 1873). William died in 1883 at the age of 59; Laura outlived him by nearly 60 years.

Along with her son Hubert and daughter Hilda, Laura Morgan-Browne was a founding member of the West London Ethical Society. She was also a committee member of the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union, founded in 1890 ‘for the propagation of sound ideas on the subject of dress’, and, in 1896, sat on the executive committee of the Central National Society for Women’s Suffrage. She was actively involved with the Women’s Liberal Federation, Women’s Franchise League, Women’s Emancipation Union, the Union of Practical Suffragists, and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Morgan-Browne was the author of ‘The Purple, White, and Green’, a WSPU song, and of an 1891 suffrage pamphlet entitled Reasons why Women Want the Franchise. She sat on the executive committee of the Women’s Progressive Society (a suffrage pressure group), alongside fellow freethinking feminists Mathilde Blind, Henrik Ibsen, Sara Hennell, Henrietta Müller, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She was a contributor to the radical feminist paper Shafts, and a lecturer on ethical and economic subjects.

As Morgan-Browne made clear in her writings on suffrage and social reform, at the root of her efforts was a firm belief in the importance of truth, faced fearlessly and in the service of progress. Like other freethinking women writers of her generation, she was well aware of the risk of being labelled ‘unwomanly’, not least in discussing matters of sex and sexism. In a tract published by the Women’s Printing Society she wrote:

First and foremost, every mother must teach her daughters the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth about the relations of the sexes, the condition of social opinion, the historical, physiological, ethical aspects of the question. She must train herself so as to be able to teach the young minds these solemn, serious aspects of life, in such a way that the world may learn that the innocence of ignorance is inferior to the purity of right-minded, fearless knowledge… I am a mother of daughters myself, and I know the cost at which the courage has to be obtained, but in this matter each mother must help another. What a mighty force is influence! What help is conveyed by pressure of opinion! How often do I remember with gratitude the words which I once read as quoted of Mrs. John Stuart Mill, who taught her little daughter to have the courage to hear what other little girls had to bear… We must reach the mass through the unit, it is the individual who helps to move the world.

Like her humanist contemporaries, including Zona Vallance and Lady Florence Dixie, Morgan-Browne used scientific knowledge and historical precedent to bolster her arguments for women’s rights, and to challenge oppressive hierarchies upheld by traditional Christian teachings. Notions of propriety could not be used to silence the voices of these women calling for the freedom to think and act for themselves, and a willingness to challenge harmful religious teachings directly was a key part of their strength.

Laura Morgan-Browne died in 1942 at the age of 99.

Laura Morgan-Browne was a devoted campaigner for the causes she believed in, whose early membership of the ethical societies sheds light on her humanist motivations. Hers was a firmly held belief in the rights of women, and their responsibility in bringing about radical change. She was also unafraid to confront those who wielded biblical notions of ‘women’s place’ to prevent their civic empowerment or restrict their autonomy. This places her firmly within a rich tradition of humanist women who prided thinking for themselves and acting for others, putting wit and word to work for radical reform.

The Humanist Broadcasting Council was established in 1959, in consultation with the BBC, to advocate for the inclusion of humanist […]

Against the militarist totalitarian state, I have striven. For the freedom of the human spirit to develop under the kindly […]

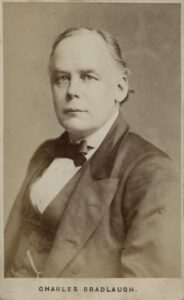

Charles Bradlaugh was a leading freethinker, secularist, and founder of the National Secular Society. His efforts to take his seat […]

Fanny Adela Coit was a suffragist and campaigner of international significance, as well as a central figure in the Ethical […]