I will call no being good, who is not what I mean when I apply that epithet to my fellow-creatures; and if such a being can sentence me to hell for not so calling him, to hell I will go.

John Stuart Mill, Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy (1865)

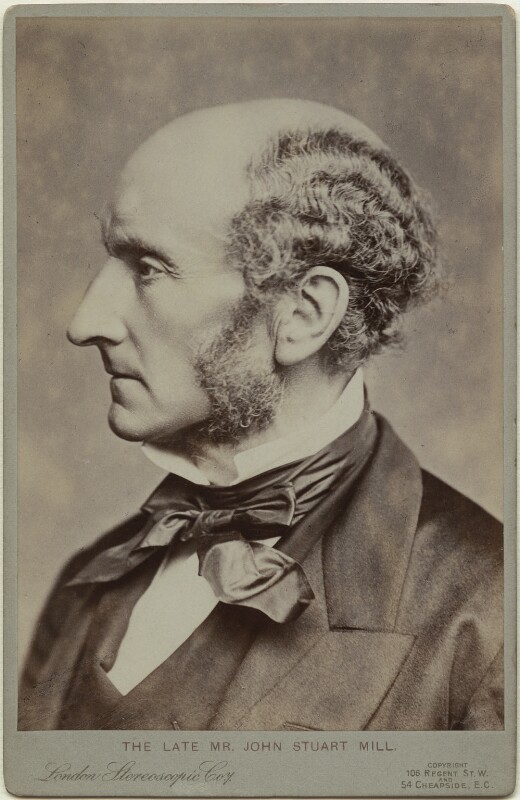

John Stuart Mill was a writer, philosopher, and feminist, who developed and applied the principles of utilitarianism in a lifelong quest for a practical, moral philosophy. Mill was an advocate of women’s suffrage, religious liberty, and freedom of the press, and described himself as ‘one of the very few examples, in this country, of one who has, not thrown off religious belief, but never had it’. Devoted to applying philosophical principles to the practical improvement of social welfare, Mill’s compassionate rationalism was deeply humanist.

When society requires to be rebuilt, there is no use in attempting to rebuild it on the old plan.

John Stuart Mill, Dissertations and Discussions (1859)

John Stuart Mill was born on 20 May 1806, the son of writer and philosopher James Mill, from whom he received a strict, rigorous, but unorthodox education. His father, a friend and follower of Jeremy Bentham, believed in the human mind as a tabula rasa: a clean slate onto which ideas and knowledge could be layered, and character moulded. John began to learn Greek at three, was introduced to Plato before the age of ten, and by twelve was widely read in the works of classical writers. He was also engaged to assist in his father’s writings, and in the education of his younger siblings.

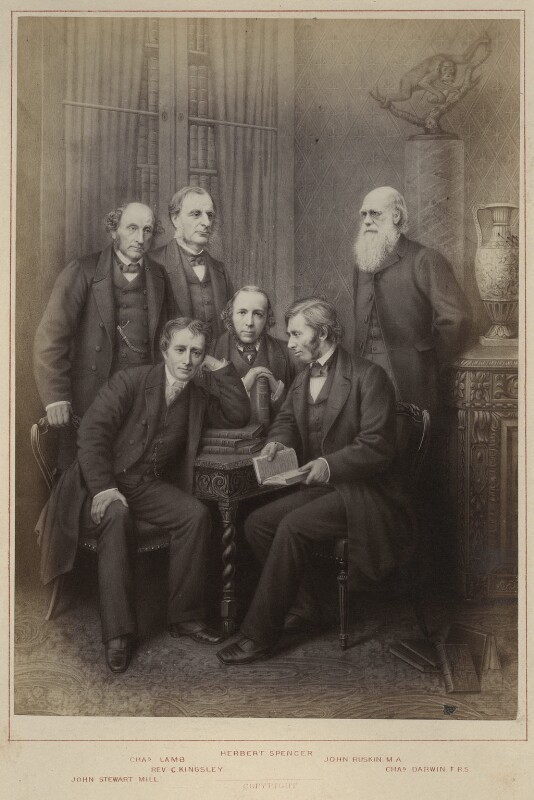

Alongside tutelage by his father and devoted efforts in self-education, Mill was surrounded by a host of prominent intellectuals, radicals, and reformers, including Bentham and Francis Place. His father, feeling that it had nothing to teach him, denied his entry to Cambridge University, insisting instead that he stay at home and work towards a legal career. Despite knowing Bentham personally, it was only while studying for law that Mill first read his writings. ‘The ‘principle of utility’,’ Mill wrote:

… gave unity to my conception of things. I now had opinions; a creed, a doctrine, a philosophy… a religion; the inculcation and diffusion of which could be made the principal outward purpose of a life.

Though Mill adopted the principles of utilitarianism as his ‘creed’, he found that the utilitarian drive to social reform did not satisfy his need for personal happiness. As such, he embraced music, art, and literature as an emotional outlet and something of a proxy for religion. His first writings on religious issues, five letters written in reaction to the prosecution of Richard Carlile for blasphemy in 1823, published in the London Morning Chronicle, defended freedom of speech enthusiastically, also questioning the claim that Christianity has a role as a moral arbiter. However, he stopped short of prescribing atheism, describing religion as satisfying a human need. In the same year, he spent three nights in jail, having been prosecuted for the distribution of birth control literature.

His 1831 collection of essays The Spirit of the Age was also restrained in its approach, looking at religion’s place in contemporary society and not attacking religious faith itself, but taking issue with organised Christianity and its social effects. During the 1840s, Mill adopted a version of Auguste Comte‘s ‘religion of humanity’, claiming that theistic religion was an expression of essentially human feelings, although it disguised these under distorting mystical illusions. Mill felt that this idea would provide the sanction for a society governed by utilitarian principles and was hesitant to attack religion out of hand for fear of scaring off potential ‘converts’ to utilitarianism. Of a possible religion of humanity, he wrote:

… we venture to think that a religion may exist without belief in a God, and that a religion without a God may be, even to Christians, an instructive and profitable object of contemplation.

Auguste Comte and Positivism (1865)

Mill’s posthumously published Three Essays on Religion, written during the 1850s, were the ultimate articulation of his religious thought. In his essay, Nature, he asserted that:

If it be said that God does not take sufficient account of pleasure and pain to make them the reward or punishment of the good or the wicked, but that virtue is itself the greatest good and vice the greatest evil, then these at least ought to be dispensed to all according to what they have done to deserve them; instead of which, every kind of moral depravity is entailed upon multitudes by the fatality of their birth; through the fault of their parents, of society, or of uncontrollable circumstances, certainly through no fault of their own. Not even on the most distorted and contrasted theory of good which ever was framed by religious or philosophical fanaticism can the government of Nature be made to resemble the work of a being at once good and omnipotent.

This essential questioning of the benevolence and omnipotence of any possible divine being was complemented by an examination of the power structures of religion and its use of authority to manipulate in his essay Utility of Religion. In his third essay, Theism, Mill put forward an agnostic view on the existence of god and, ultimately, he never fully resolved the issue of his religious views, preferring constant re-examination of his beliefs to any subscription to dogma, religious or otherwise.

During the 1860s, Mill took up many of the radical decade’s radical causes. These included the defence of birth control, challenges to the Contagious Diseases Acts, calls for proportional representation, and active support of women’s suffrage. Between 1865-8, he was Member of Parliament for City and Westminster, during which time he advocated land reform in Ireland, and in 1866 became the first person in Parliament to call for women to be given the right to vote. In 1869’s The Subjection of Women, an essay drawing on ideas developed in partnership with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill, he attacked the commonly used argument that women’s supposed moral superiority rendered them best suited to the home. To Mill, this was merely an:

empty compliment, which must provoke a bitter smile from every woman of spirit, since there is no other situation in life in which it is… considered quite natural and suitable, that the better should obey the worse. If this piece of idle talk is good for anything, it is only as an admission by men, of the corrupting influence of power…

Mill attributed much inspiration, support, and co-authorship to his wife, ‘whose exalted sense of truth and right’ he named as his ‘strongest incitement’.

John Stuart Mill died on 7 May 1873 in Avignon, France, where he was buried. His last words to his stepdaughter and devoted companion, Helen Taylor, were: ‘you know that I have done my work’.

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859)

John Stuart Mill was a lifelong examiner of ideas and defender of human freedom, whose own pursuit of a rational, compassionate, and satisfying philosophy for living has given much to humanists today. Mill was a passionate advocate of the rights of women, and a devoted champion of freedom of speech and expression – just two of the causes consistently taken up by humanists throughout history. His influence on the growing culture of 19th century agnosticism was also significant, his writings and actions serving as proof for principled unbelief.

His legacy was directly felt, in part, through the life of Helen Taylor, who continued to promote women’s rights and agitate for humane social reforms. She was also a vocal supporter of the Ethical movement, describing the ethical societies as among the closest to her heart, and stating her particular admiration for humanist educationist F.J. Gould.

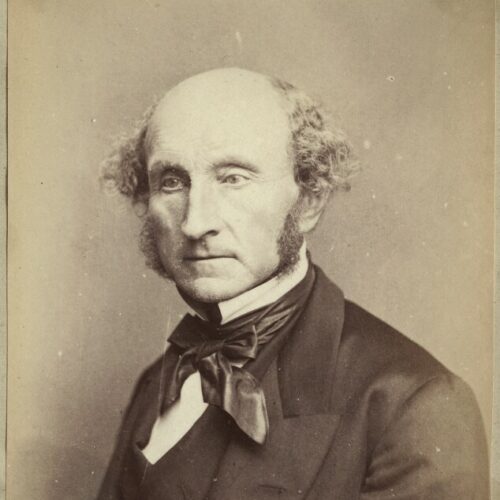

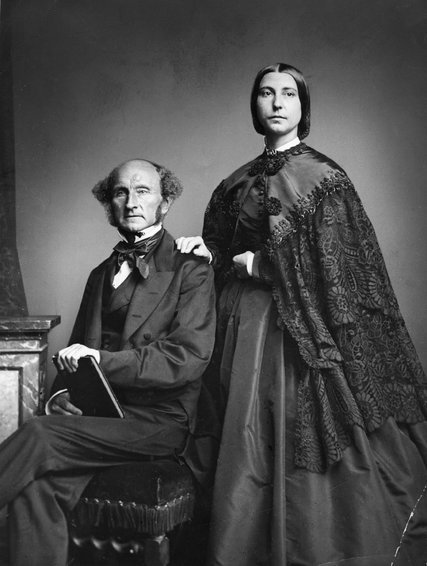

Main image: John Stuart Mill by John & Charles Watkins, 1865 © National Portrait Gallery, London

I have no view but public good; certainly no desire to injure any one, but a passionate desire to do […]

I will call no being good, who is not what I mean when I apply that epithet to my fellow-creatures; […]

No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, […]

Women, like men, should try to do the impossible. And when they fail, their failure should be a challenge to […]