From the outset IAS aimed to have an open approach to prospective adopters irrespective of their race, religion and creed, and to find homes for all children in need.

Mary James, former director of the Independent Adoption Society

The Agnostics Adoption Society was formed in 1963, with a committee which included representatives from the British Humanist Association (Humanists UK) and the National Secular Society. This humanist and inclusive organisation sought to secularise adoptions, during a time when most were undertaken by church-based agencies and the process favoured those professing a religious faith. Then, as today, humanists knew that the non-religious could provide loving homes and moral guidance to adoptive children just as religious people could, and the organisation – which became the Independent Adoption Society – was pioneering in its work against discrimination of any kind in the realms of adoption.

The Agnostics Adoption Society was established in 1963, and registered as a charity (and with the London County Council) in 1965. It came at a time when adoption was dominated by religious organisations, and was formed explicitly to facilitate adoptions without assessment based on religious affiliation. During this first decade, they also became a founding member of the Adoption Resource Exchange, formed to meet the challenge of finding homes for mixed race children. From the early 1970s, they pursued an active policy of finding suitable homes for children with special needs, blazing a trail for collaborative working across agencies in the area of adoption.

Central to the Society’s formation were Richard Doll, an epidemiologist, and his wife Joan Mary Faulkner, secretary of the Medical Research Council, who founded it with the advice of the British Humanist Association. The couple (both non-religious) had adopted their own two children a decade earlier, but the process had been made significantly more difficult by the dominance of faith groups in facilitating adoptions. They raised their own funds to establish the society, which was initially based in their home, and hired its first social worker, Jayne Dunbar. Their aims for the society were:

To help would-be adopters from minority as well as majority groups, people from all religions or none, and not to turn away any child who it is within our power to help. Babies which other agencies have classified as difficult we accept gladly.

Another initiator of the group was Marjorie Mepham, who, along with her husband George, had struggled to adopt as a professed agnostic. The couple, both humanists, were eventually able to adopt twin boys, and – wanting their children to know of the wider community who shared their beliefs – founded the Sutton Humanist Group, which became one of the UK’s largest. As similar struggles to those experienced by the Dolls and the Mephams made their way into the press, and to the British Humanist Association, the need for the Society had been made clear. The first president of the Agnostics Adoption Society, elected in 1965, was humanist A.J. Ayer, who was also president of the BHA. By the end of 1966, the Society had overseen the adoptions of nine babies, and received over 2000 letters from prospective adopters.

In 1969, the society was renamed the Independent Adoption Society. The year also marked the end of Richard Doll’s direct involvement in the charity’s operations, but it remained a progressive force among adoption agencies in the UK.

From 1972, the IAS adopted an active policy of finding homes for children with special needs, emerging as an authority on best practice. They encouraged a collaborative and explorative approach to recruiting, preparing, and supporting adoptive parents, which emphasised sharing experiences and placing the child at the centre of decision-making. This included exploring different ways to evaluate the suitability and success of different placements, such as taking a day trip rather than (or as well as) conducting a formal interview.

In 1980, the IAS and the London Borough of Lambeth established the New Black Families Unit, aimed at finding suitable homes for black children in care. Building on the earlier Soul Kids Campaign, the NBFU was staffed by black employees, who recruited and assessed black families as potential foster and adoptive parents. The project helped to demonstrate the demand for adoptive children from black families, and its success helped to motivate other local authorities and voluntary agencies to follow suit. It also encouraged a more community-based approach within the IAS, acting on local knowledge and working closely with key community members. The NBFU became a touchstone within wider discussions surrounding interracial adoption.

The Independent Adoption Society gained a reputation as among the most responsible and progressive agencies in the UK. Its first social worker, Jayne Dunbar, remained with them for 27 years. Emerging as it did in response to biases in the adoption process, the Independent Adoption Society sought from its outset to challenge discrimination, embody inclusivity, and apply humanist values to facilitating adoption. As such, collaboration, compassion, and a reasoned, evidence-based approach underpinned its efforts, and enabled its progressive role within the wider field.

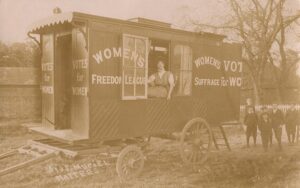

Dare to be free. Slogan of the Women’s Freedom League The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was a militant suffrage organisation, […]

To those who regard the furtherance of International Good Will and Peace as the highest of all human interests, the […]

Without any great effort of thought, I believe that I could, in an instant, propose other systems of cosmogony, which […]

Love is a kind of courage, and, in the hearts of the man and woman who will here wed, there […]