Every movement requires its handful of pioneers who are prepared to stand up and be counted — to be abused, ridiculed and denounced by the religious and the conventional for seeing the truth prematurely. Determination, self-confidence, persistence and resilience are the vital qualities reformers need, and Janet Chance, Stella Browne, Alice Jenkins and their colleagues in those early years possessed them in great measure.

Madeleine Simms and Keith Hindell, Abortion Law Reformed (1971)

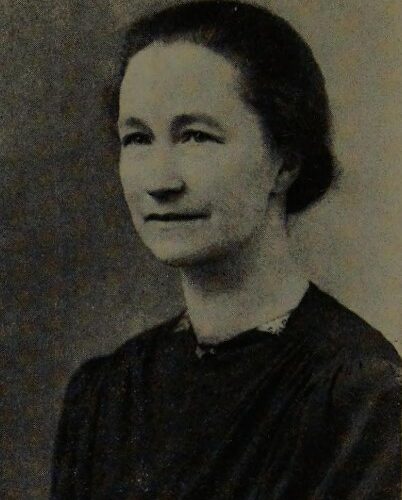

Alice Jenkins was a humanist who campaigned for the legalisation of abortion for almost four decades, and was a founding member of the Abortion Law Reform Association. Her book Law For The Rich convinced David Steel MP that abortion law reform was essential, causing him to bring forward the private member’s bill which became the Abortion Act 1967. Alongside other humanist campaigners, including Dora Russell and Stella Browne, Jenkins sought a transformation in public attitudes towards sex and morality, and placed special emphasis on the rights of the working class.

Alice Jenkins was born in Ilkley, Yorkshire to Charlotte Glyde, a single mother. One of six children, each of Jenkins’ siblings went on to be active in radical politics. She won a scholarship to her local grammar school but was unable to progress to university for financial reasons. She thus continued her education as a pupil teacher until her marriage. Jenkins then moved to London where her three children were born.

Having raised her family, Jenkins learnt through her membership of the Women Citizens Association that the high rate of maternal mortality was partly due to deaths resulting from attempts to self-induce abortion. Finding this unacceptable, she joined the National Birth Control Association (later the Family Planning Association) and campaigned alongside fellow humanists Stella Browne, Frida Laski, Dora Russell, and Dorothy Thurtle for birth control advice to be made available in local medical clinics. Jenkins was also involved with the Workers’ Birth Control Group, which sought to enable working class women to access information about birth control.

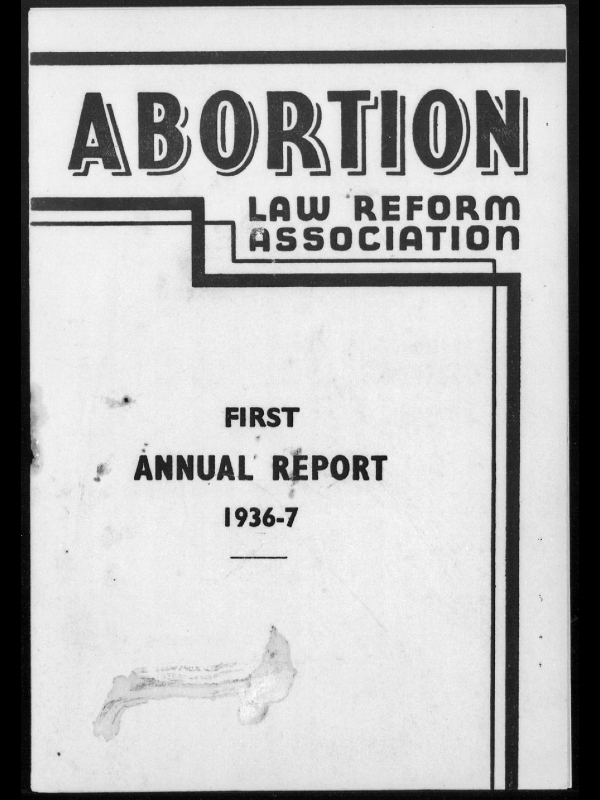

Jenkins became convinced that greater awareness of contraception would not in itself end the deaths caused by both self-induced and unskilled ‘back-street’ abortions. So in 1936, together with Stella Browne, Janet Chance and others, she founded the Abortion Law Reform Association, and the following year they submitted evidence to the Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (or Birkett Committee). The Committee recommended that abortion should be legal when needed to save a woman’s life or to preserve her health, but the outbreak of war prevented these recommendations from being implemented.

Jenkins, Chance and Browne managed to keep ALRA in being during the war, and in 1945 they reconstituted the organisation with Jenkins as Secretary. But the outlook was discouraging. Abortion was still euphemistically referred to in both the press and in parliament as ‘the illegal operation’, and Jenkins felt unable to tell family friends that she was a member of ALRA. However, in 1951 the Pope informed a congress of Italian midwives that the termination of pregnancy was wrong even when needed to save a woman’s life. The strong reaction against this pronouncement persuaded ALRA that the time was ripe for a private member’s bill and Joseph Reeves MP, a Vice President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), agreed to bring one forward. Jenkins threw herself into the task of lobbying, but many MPs were wary of the Catholic vote in their constituencies and Reeves’ bill was talked out. Even so, it was now clear that many MPs favoured reform, and further impetus was given to ALRA’s campaign when the public became aware of the thalidomide tragedy.

In 1960 Jenkins published her book Law For The Rich, which set out the case for abortion law reform. Jenkins pointed out that most of those seeking an abortion were married women who already had several children. And although those with financial means were able to obtain safe therapeutic abortions, working class women were forced to resort to dangerous ‘back-street’ abortions. Jenkins also questioned why the Catholic church had an influence on the issue out of all proportion to its numbers.

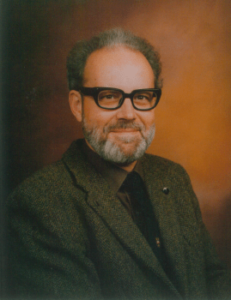

In 1966 David Steel MP read Jenkins’ book and found it ‘movingly impressive’. A series of parliamentary bills sponsored by ALRA had built cross-party support for reform, and Steel was further encouraged by the fact that leading members of ALRA were experienced and effective parliamentary lobbyists. He consequently brought forward his own bill and, despite fierce opposition from Catholic MPs, the bill passed both Houses of Parliament and became the Abortion Act 1967.

Jenkins had retired from ALRA at the age of 76, but lived to see the Abortion Act come into law. The last surviving member of the original ALRA committee, Alice Jenkins died in London on 25 December 1967, eight weeks after the Act received royal assent.

Alice Jenkins was remembered by Dora Russell as being ‘frail but determined’, and by the authors of Abortion Law Reformed as supplying ‘the essential administrative gifts that were required to maintain the organization [ALRA] in being’. Like the other humanist members of ALRA, Jenkins believed in freedom of choice, and was an indefatigable defender of her cause against fervent religious and socially conservative challengers. Jenkins observed that she had written Law for the Rich ‘only because of my hatred of preventable suffering’. The result of her compassion was a defining role in the success of a major piece of reforming legislation, helping to secure safe, legal abortions for women.

Alice Jenkins, Law for the Rich: A Plea for the Reform of the Abortion Law (1960)

Madeleine Simms and Keith Hindell, Abortion Law Reformed (1971)

David Steel, Against Goliath: David Steel’s Story (1989)

Alice Jenkins | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

By Paul Ewans

Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays. […]

Auguste Comte was a French writer, philosopher, and social scientist, whose theory of positivism was a significant influence on the […]

Humanism involves not just the deletion of God from moral thought, but the development of humanity on a rational and […]

There is nothing in this world to compare with the joy of finding something to do that one believes to […]