I see this kind of love – the empathy that should be common to all living creatures – rather than religious and intellectual approaches, as the possible reconciling force for peace in the world, and as the basis for the care and education of children.

Dora Russell, The Tamarisk Tree: my quest for liberty and love (1975)

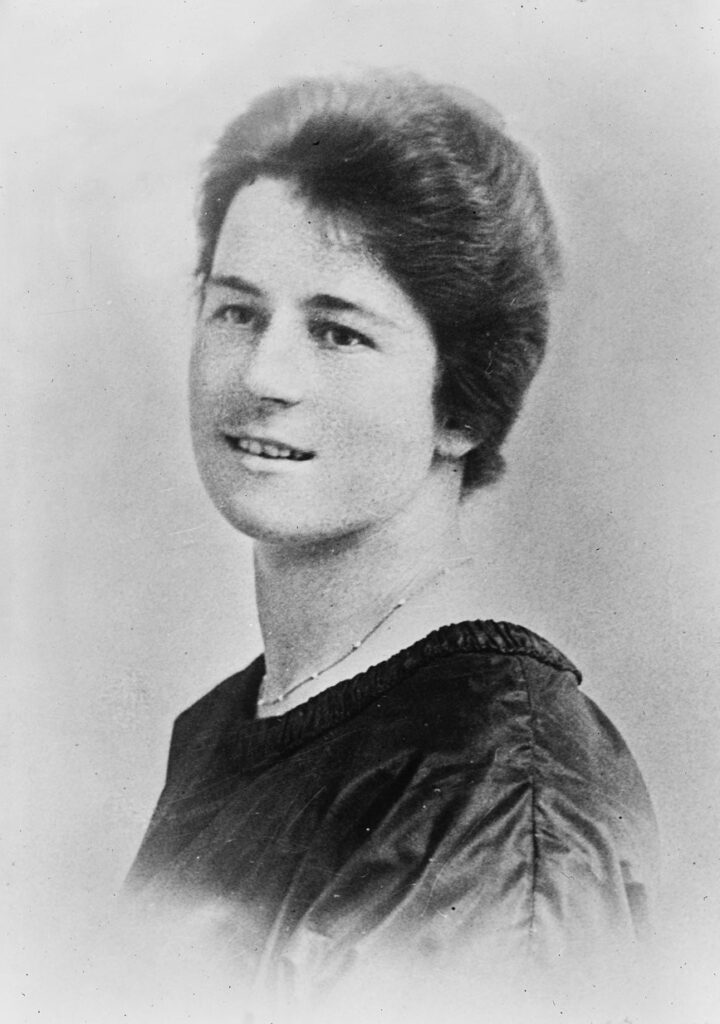

Dora Russell (née Black) was a writer, activist, and school founder: a feminist, pacifist, and a deeply eloquent humanist. Throughout her long life, Russell was committed to improving the world for others, driven not by any religious sense, but by an abiding belief in the value of humanity, and the individual’s role in creating positive change.

Over her life, Russell was a perpetual and fearless interrogator of the world’s customs and assumptions (not least when based upon religion), enlightening her outlook with the study of history and philosophy, and championing the intellectual, economic, and reproductive rights of women for more than half a century.

Bertie and I, for all the individualism of our personal lives, were inspired by an abiding sense of responsibility to humanity. Priggish as this attitude may sound, we could not divest ourselves of it.

Dora Russell, The Tamarisk Tree: my quest for liberty and love (1975)

Dora Russell was born on 3 April 1894 in Croydon, the second child of Sir Frederick William Black and Sarah Isabella Davisson. Her life would be, as she herself wrote, ‘the story of a girl growing up from an Edwardian childhood through the period of women’s emancipation, changing sex relations, the expansion of industrialism, revolution and the rising of the working class.’ In all of which, she added, her ‘personal life and thought were involved.’ Frederick Black believed in educating his three daughters as he did his son, and Dora went up to Girton College, Cambridge, where in 1915 she obtained a first class degree in medieval and modern languages. At Girton she was drawn to religious and philosophical questions, these ‘moral and theological disputes’ becoming ‘part of the central dilemma’ of her life.

It was at Girton that she began to shed the Christian beliefs of her childhood. The poetry of George Meredith was a part of this, as was the intellectual atmosphere of Cambridge and its influential Heretics society. ‘Thus it was,’ recalled Dora, ‘gradually, that I came to reject the religion in which I had been brought up and to form by degrees a view of life by which to determine my actions’. This encompassed a reexamination of the individual’s place in the world, and, significantly, a growing awareness of the position of women, so affected by biblical notions of femininity and hierarchy.

Her closest friend at Girton was Dorothy ‘Dot’ Wrinch, a mathematician and chemist, who accompanied her to meetings of the Heretics. Founded in 1909 and inaugurated with a lecture from pioneering classicist Jane Ellen Harrison, the Heretics had been formed in direct opposition to compulsory worship at Cambridge. The embrace of ‘heresy’, a humanist philosophy of thinking freely with appeal to reason, was formative. Writing six decades later, she would recall how:

…we women at Girton had, before long, discovered the Heretics Society. Not very many of us, I regret to say. Instead of favouring holy retreats at occasional weekends, or going to College chapel on Sunday evenings, we would ask for an exeat permit and be off to Heretics. This was not much favoured at the top level in Girton, but it was not forbidden. C. K. Ogden, who was the prime mover in the Heretics, was to become one of my real friends and a considerable influence in my life. He had a flat high up in Petty Cury, which he called Top Hole. It was here that the Heretics used to meet. I used to bicycle off there of a Sunday evening with a most agreeable feeling of defiance and liberation. If you joined the Society you were called upon to reject authority in matters of religion and belief, and to accept only conviction by reasonable argument. You could, if not certain of your position, become an associate, who merely believed in open discussion but had not entirely rejected authority.

Dora retained her rejection of authority, in all she could not square with reason and compassion, for the rest of her life.

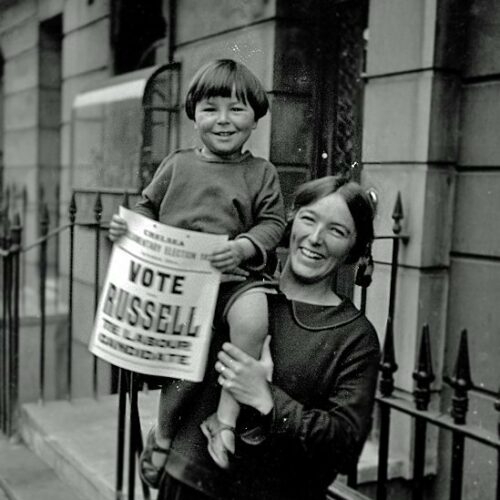

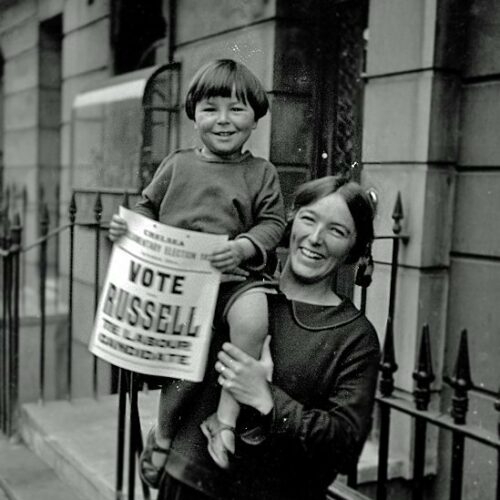

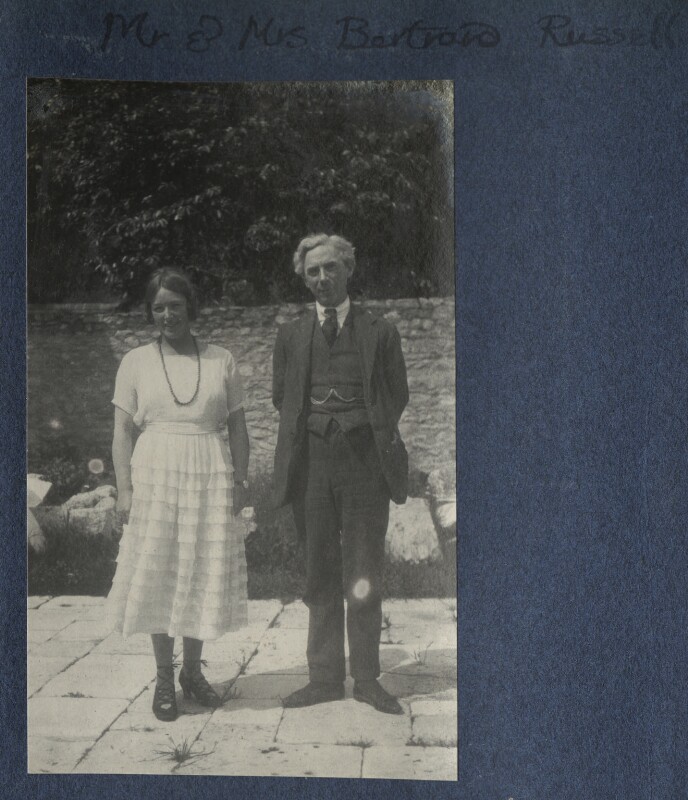

In 1921, Dora Black married philosopher, pacifist, and humanist Bertrand Russell, who she had met five years earlier. Two months later, she gave birth to their first child, and the couple moved together to Chelsea. Throughout the following decade, in defiance of her fears that people ‘would simply believe that all my ideas were derived from Bertie’, she threw herself behind causes that would remain at the heart of her activism. Russell, alongside fellow freethinker and feminist Stella Browne, became a leading proponent of women’s reproductive rights. In 1924, she helped to form the Workers’ Birth Control Group to provide advice on birth control to working class women. In the same year, she ran unsuccessfully as Labour candidate for Chelsea.

In 1927, the Russells founded Beacon Hill, a progressive school on the South Downs, which – in Dora’s words – ‘seemed a place in which children might be healthy and happy’. Here, her philosophy on freedom, openness, and the supreme value of happiness, underpinned the ethos of the school, which she saw as a microcosm of a broader experiment:

We were, in the school, running a wider free community, in which the harmony of human relations was a vital element… a bit of rampaging could do no harm and children could learn that orderly behaviour ultimately arose out of living together, and not from the commands handed down by the authority of parents and teachers.

Though ridiculed in the press, Russell maintained a lifelong sense of pride in the ideals embodied by Beacon Hill. Socialist suffragist Sylvia Pankhurst’s son, Richard, was a day boy at the school, which Dora Russell ran until 1943 (the last eleven of which were without Bertrand).

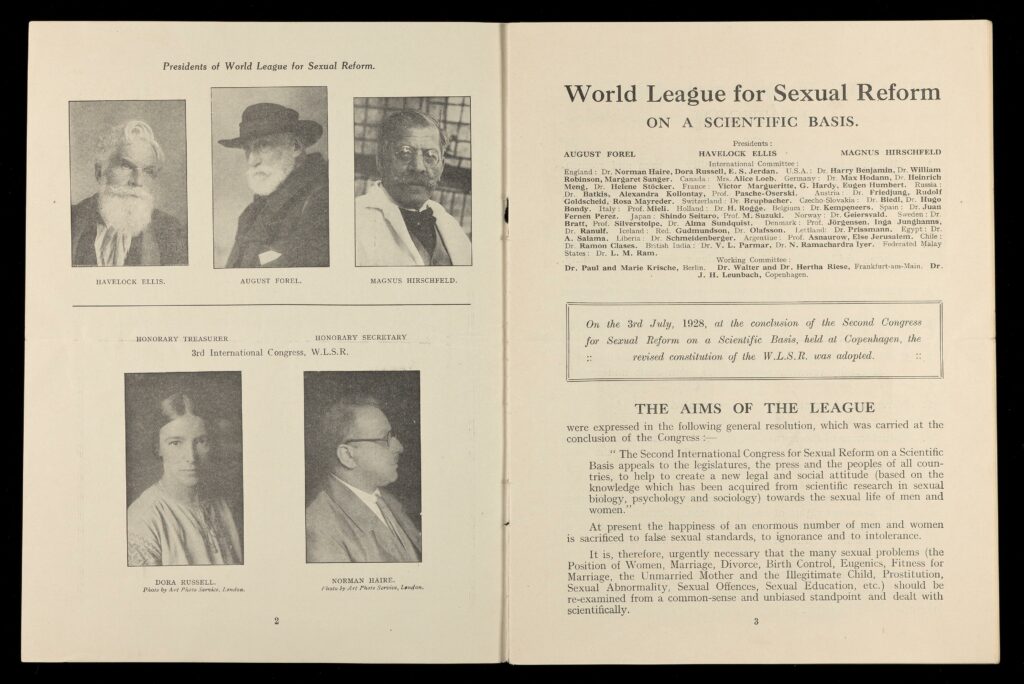

A central belief in the transformative possibilities of open attitudes in matters of sex and sexuality animated much of Dora Russell’s life during these decades and beyond. She became founding Secretary of the English branch of the World League for Sexual Reform, led by Norman Haire, and was instrumental in organising the 1929 Congress of the League, which took place in London. ‘If anyone wishes to know who were the standard-bearers of progressive opinion in the chief European countries at that date,’ she wrote, ‘the index of the participants is a reliable guide.’ Among them were C.E.M. Joad, Naomi Mitchison, Stella Browne, Laurence Housman, Bertrand Russell, and George Bernard Shaw. ‘To me,’ she wrote:

…this Congress had meant more than I can say. It had begun to outline those things in which I ardently believed; it had, moreover, expressed an internationalism that went beyond mere politics… We had passed resolutions on marriage and divorce, sex and censorship, sex education, birth control, abortion, prostitution, and venereal disease, which might serve as a basis for a tolerant and humane society…

She was a founding member of the Federation of Progressive Societies and Individuals in 1932, of the National Council for Civil Liberties in 1934, and of the Abortion Law Reform Association in 1936.

After closing Beacon Hill School in 1943, Russell went to work for the Ministry of Information, and saw out the decade working in the Soviet relations division. From 1950 onwards, she devoted herself wholeheartedly to the movements she had long supported, particularly feminism and pacifism, becoming active in the Six Point Group, the Married Women’s Association, and the Women’s International Democratic Federation. In 1958, she organised the Women’s Caravan of Peace: a march across Europe to Moscow at the height of the Cold War, calling for peace and disarmament. She would go on to lead, at 89, a Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament rally in London, actively campaigning for peace until days before her death.

Dora Russell died on 31 May 1986 at her home in Porthcurno, Cornwall. Her ashes were scattered in the garden there.

Dora Russell epitomised the humanist willingness to challenge tradition and champion progress, retaining this devotion to the very end of her days. A member of the Rationalist Press Association from 1927, Russell delivered the opening address to its annual conference in 1974. She used her speech, titled ‘The Long Campaign’, to call for the kind of human cooperation and radical reshaping of society which had underpinned a life of activism. ‘I am convinced,’ she said, ‘that some great revolutionary humanist beliefs must come about if we are to survive’. In this:

I hope that the long campaign of woman through history to reach her rightful place will contribute fully… and share with dignity the shaping of a people and destiny worthy of the name of human.

Max Gate is the former home of Thomas Hardy in Dorchester, Dorset. Hardy designed and lived in Max Gate from 1885 until […]

Emancipation from every kind of bondage is my principle. I go for the recognition of human rights, without distinction of […]

I might fill columns with tales of the debaters, co-operators, socialists, individualists, critics, artists, scientists, clergy and cranks, who, as […]

The National Secular Society is a campaigning organisation, founded in 1866 to champion the principles of secularism and the separation […]