Women, like men, should try to do the impossible. And when they fail, their failure should be a challenge to others.

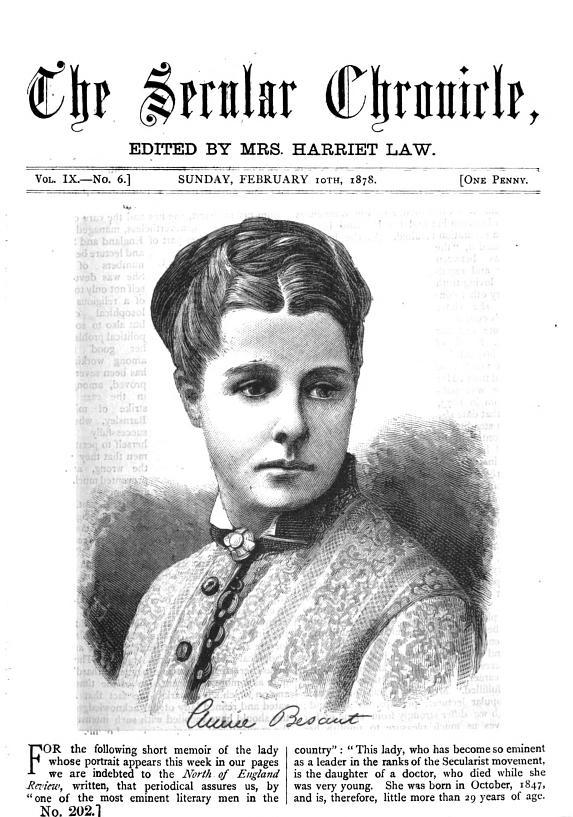

Annie Besant

Annie Besant was a socialist, activist, and champion of human freedom, who became a leading figure in the secularist movement during the 1870s and 1880s. Abandoning the strict Christianity of her upbringing and early adulthood, Besant wrote, lectured, and organised for the National Secular Society, risking her reputation – and custody of her children – in the process. In defence of press freedom and support of self-determination, Besant published and defended birth control literature, and advocated for the rights of working women through the Matchgirls’ Strike of 1888. Although she later turned to theosophy, she had already left a considerable impression on the history of humanist and secularist thought and action in the 19th century, and inspired many others by her example.

Annie Besant was born into a London family of Irish origin on 1 October, 1847. By the standards of the time she had an excellent education and travelled widely in Europe.

As a young woman she was religious and at the age of 20 married a 26 year old clergyman, Frank Besant. The union was soon to produce two children, Arthur and Mabel. However, the marriage was anything but a success and the couple disagreed on a host of social and political issues. Annie always supported the radical and progressive side, Frank the conservative. Matters came to a head when Annie began to have doubts about her faith and refused to attend Communion. In 1873 they separated and Annie moved with her daughter to live in London.

On 9 August 1874 Annie attended the Old Street Hall of Science for the first time, joined the NSS and met Charles Bradlaugh. Bradlaugh was immediately struck by the young firebrand who was soon contributing to Bradlaugh’s journal The National Reformer. On 25 August she delivered her first lecture on ‘The Political Status of Women’ in which she denounced religion for keeping women subordinate. Like Bradlaugh, she was a brilliant speaker and was soon criss-crossing the country, speaking on all the most important issues of the day demanding improvement, reform and freedom. Bradlaugh’s daughter, Hypatia, wrote:

She was very fluent, with a great command of language, and her voice carried well; her throat, weak at first, rapidly gained in strength, until she became a most forcible speaker. Tireless as a worker, she could both write and study longer without rest and respite than any other person I have known… Though not an original thinker, she had a really wonderful power of absorbing the thoughts of others, of blending them, and of transmuting them into glowing language. Her industry, her enthusiasm, and her eloquence made of her a very powerful ally to whatever cause she espoused.

Annie Besant was thus a forceful, attractive firebrand who quickly established herself as Bradlaugh’s trusted companion. In 1877 she helped persuade Bradlaugh to republish Charles Knowlton’s birth control pamphlet, The Fruits of Philosophy. Although this venture was successful it had a tragic outcome: in the wake of the trial Annie lost custody of her daughter Mabel to her estranged husband, Frank.

In the years that followed Annie was to become founding secretary of the Malthusian League (the forerunner of the Family Planning Association) and wrote numerous pamphlets and books on progressive themes including her own birth control pamphlet The Law of Population which was to sell around 175,000 copies. She could write about historical topics, science, religion, women’s rights and philosophy, all from a freethinking perspective. She founded her own journal, Our Corner, as well as loyally supporting Bradlaugh throughout his parliamentary struggle.

By the mid-1880s she was increasingly influenced by the growth of socialist ideas and joined the Fabian Society in 1885. Besant hoped she could blend the outdoor activism of the secularists with the armchair socialism of the Fabians. Although her stance was popular with some secularists it created tensions with Charles Bradlaugh and his successor as President of the National Secular Society, G.W. Foote. Their perspectives were those of individualistic radicals rather than collectivistic socialists. However, Annie remained a member of the NSS for a few more years.

On 13 November 1887 she was a speaker at a protest meeting in Trafalgar Square which became known as ‘Bloody Sunday’. In 1888 she played an important role in the London Matchgirls’ Strike and was also involved with the London dock strike of 1890, both of which were successful. These strikes were central to the formation of trade unions for the unskilled.

By the 1880s Besant was moving away from secularism and when, in 1889, she started taking an interest in theosophy, it was clear that her time as a secularist was over. In 1893 she moved to India and devoted the rest of her life to theosophy and the cause of Indian nationalism.

Many secularists were both bewildered and disappointed. They remembered the young woman who had inspired their struggle for a better world. They mourned their loss particularly as it occurred as Bradlaugh’s health declined.

Annie Besant died on 30 September 1933, a few days before celebrations of the centenary of Bradlaugh’s birth. Those who remembered Bradlaugh remembered her too and her contribution to the secularists’ cause.

In her determination to pursue freedom of thought, and defend the rights of others, Annie Besant left a significant legacy in each of the movements of which she was a part. During a period when Christianity and respectability were still synonymous in the public mind, Besant risked security, reputation, and social standing in her declaration and defence of atheism. As a driving force in publishing the Fruits of Philosophy, and within the Malthusian League, she remains a key figure in the long history of humanist and secularist support for reproductive choice, continued in the work of Humanists UK today.

By Robert Forder

No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, […]

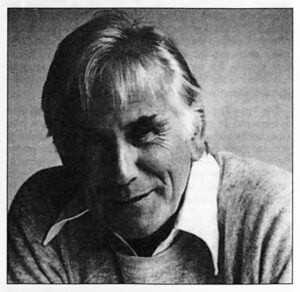

George Broadhead was a humanist activist and gay rights campaigner, motivated by a twin commitment to humanism and human rights. […]

Emancipation from every kind of bondage is my principle. I go for the recognition of human rights, without distinction of […]

At this nervous moment… when we have uncertainties about almost everything, it’s particularly necessary that we pool our determination, so […]