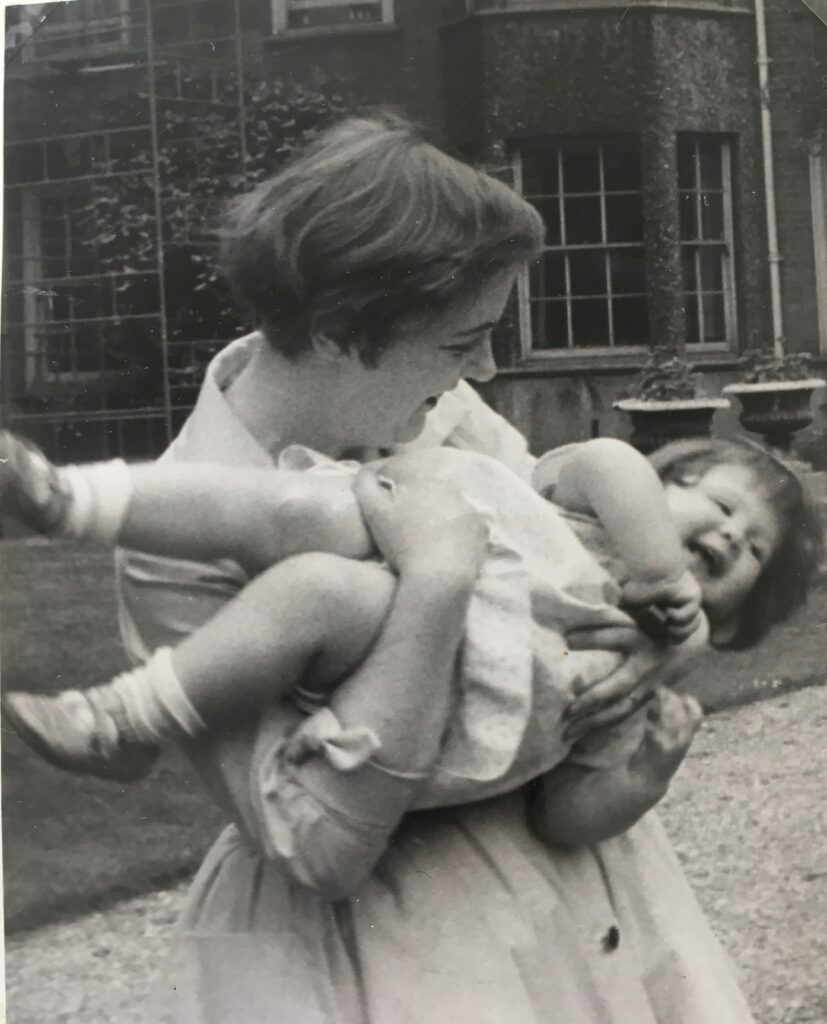

I know it sounds like an elocution exercise, but being brought up by Brigid Brophy was, on balance, brilliant.

Both my parents were humanists and they determined that my upbringing should be solidly rational. That bedrock gave me stability and my mother, specifically, steered me from the kind of emotional jumble she had grown up with. Matters were explained to me from the earliest, in terms I could comprehend; that included my own interior feelings, so in a sense I was inducted into Freudian theory, which Brigid had studied and found compelling. But it was always stressed that not everyone held the same views. I was not force-fed intellectual ideas. Rather, I imbibed a pragmatic, rather comforting knack of cool appraisal, and eventually the skill of reasoned scepticism. None of that, though, conveys the gloriously imaginative, affectionate, colourful and secure childhood I experienced; one full of interesting activity, material indulgence and fun.