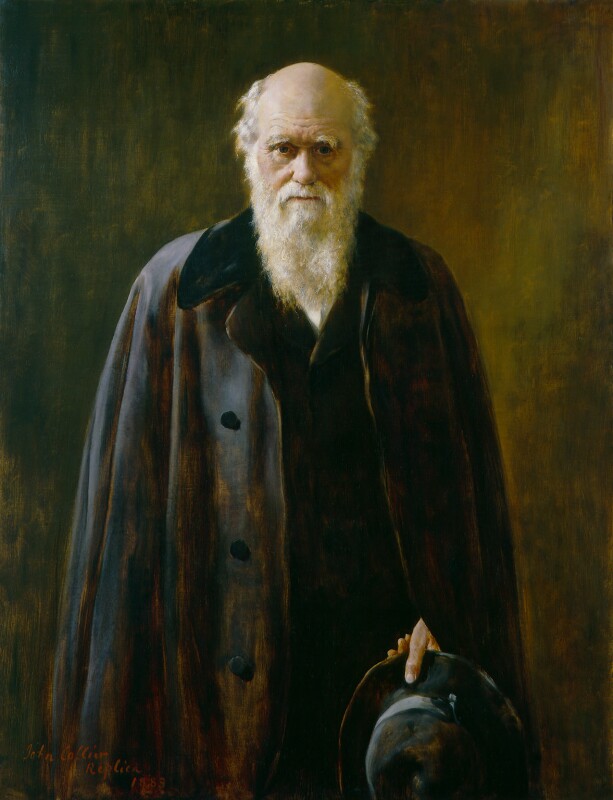

Charles Darwin (1809–1882)

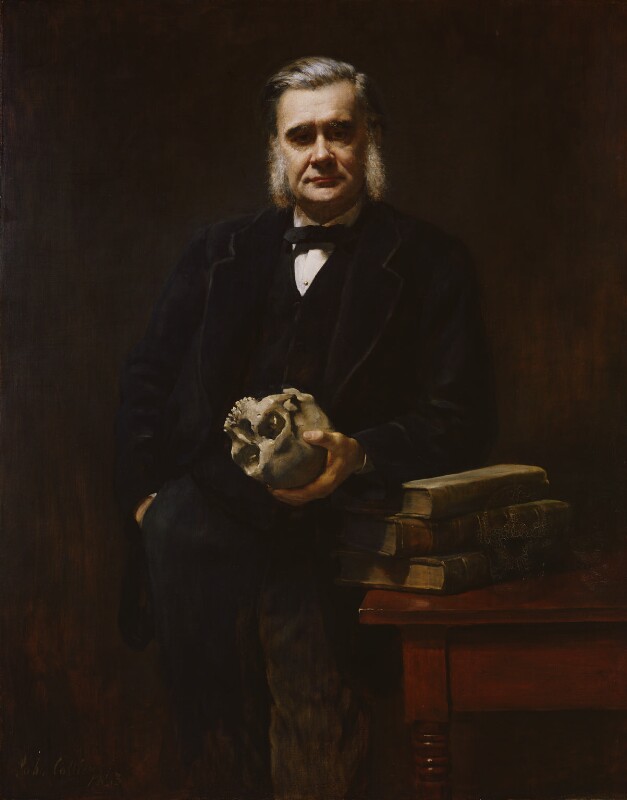

Charles Darwin, founder of evolutionary biology, profoundly changed the way people saw the world, understood the past, and made sense of humanity itself. With the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, Darwin laid out the concepts of evolution by natural selection, and established a discipline which brought scientific and historical methods together. Adopting the word coined by T.H. Huxley, one of his most prominent defenders, where religion was concerned Darwin ultimately came to describe himself as ‘agnostic’.

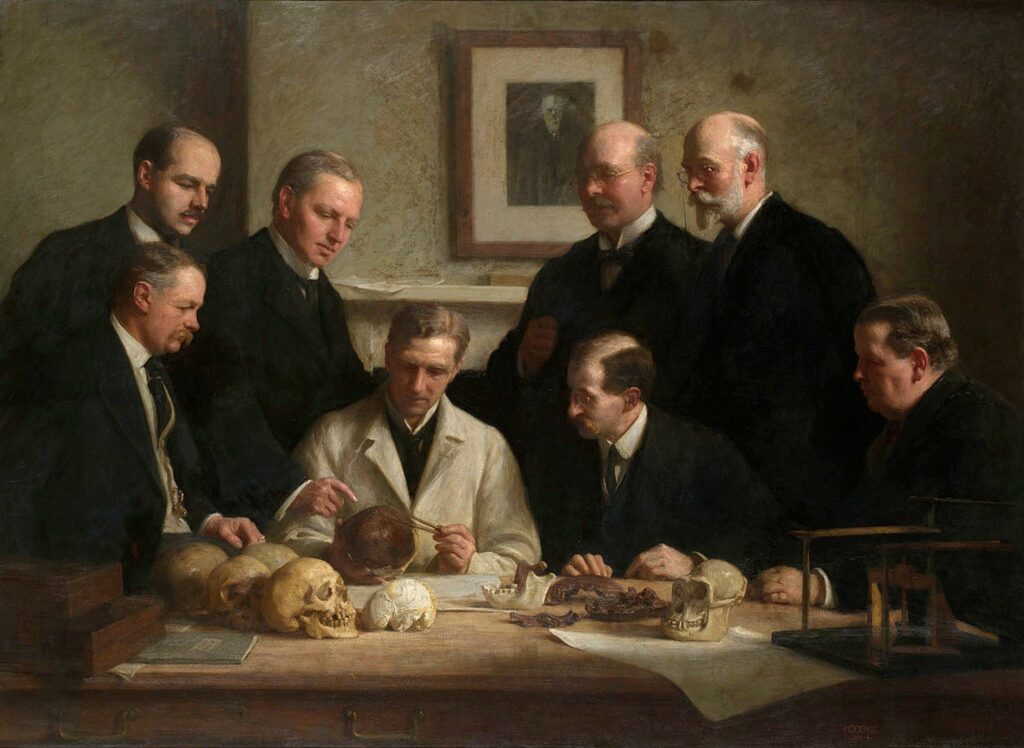

Evolutionary biology emphasised careful observation and comparison, as well as the evaluation of differing interpretations of evidence in explaining change over time. Following the science where it led, even where it challenged commonly held beliefs, epitomised Darwin’s devotion to his discipline, and enabled a theory which underpins our understanding of biology – and history – today.

Watch: Sir David Attenborough discusses Charles Darwin

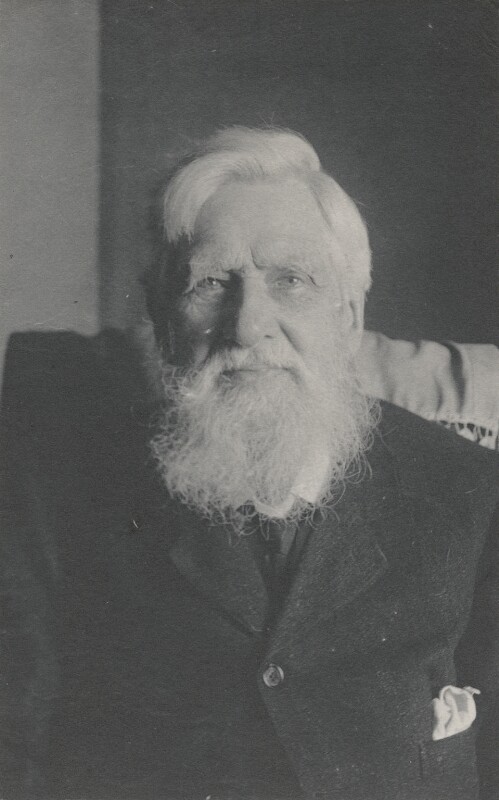

The figures below are just a small selection of those who interacted with, were inspired by, or have continued to respond to the theories and legacies of Charles Darwin.