Those who, like myself, are in communication with the advanced thought and thinkers throughout the world know that hundreds —nay, thousands—of women have thrown off the yoke of superstition and are thinking for themselves and working for others.

Lady Florence Dixie, Towards Freedom, 1904

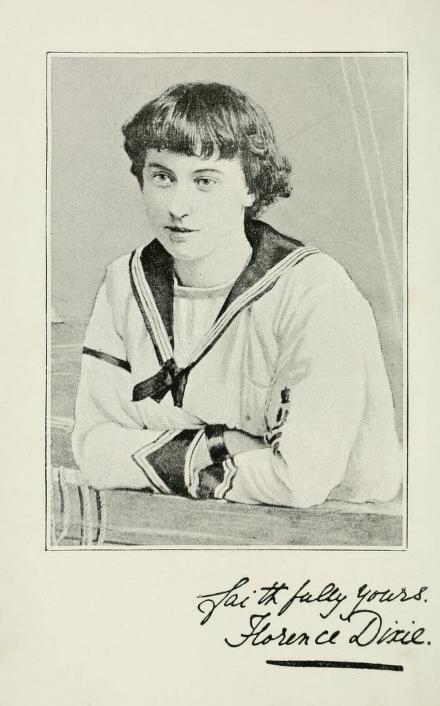

Florence Dixie was a writer, war correspondent, suffragist, and traveller, who threw off the restraints of Victorian domesticity to pursue adventure and advance her causes. Dixie argued for complete equality between the sexes, for amendments to the marriage service and divorce law, as well as for the abolition of blood sports. She was a supporter of Irish home rule and contributor to The Agnostic Journal. A fierce advocate of rational and empathetic reform, Dixie championed many of the values central to humanism today, and brought a distinctly feminist viewpoint to bear on her criticisms of religion.

The Bible is the charter of women’s serfdom, and, as a consequence, of man’s degradation. It, like all superstitious God-books, is the outcome of ignorance ruled by selfishness.

Lady Florence Dixie, Towards Freedom, 1904

Lady Florence Dixie was born in Cummertrees, Scotland on 24 May 1855, the youngest of six children born to Archibald William Douglas (the eighth marquess of Queensberry) and Caroline Margaret, née Clayton. Florence was affected by a number of tragedies over the course of her life. Her father died by accidental gunshot in 1858, and her brother, Francis, was killed in 1865 ascending the Matterhorn. Florence’s twin brother James committed suicide in 1891.

Despite an at times turbulent childhood, and a repressive education at a convent school, Florence excelled at sport and enjoyed poetry. In her earlier years she was an avid hunter of big game, though she would later disavow the pursuit and become a supporter of The Humanitarian League. In 1875, at 19, she married Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie.

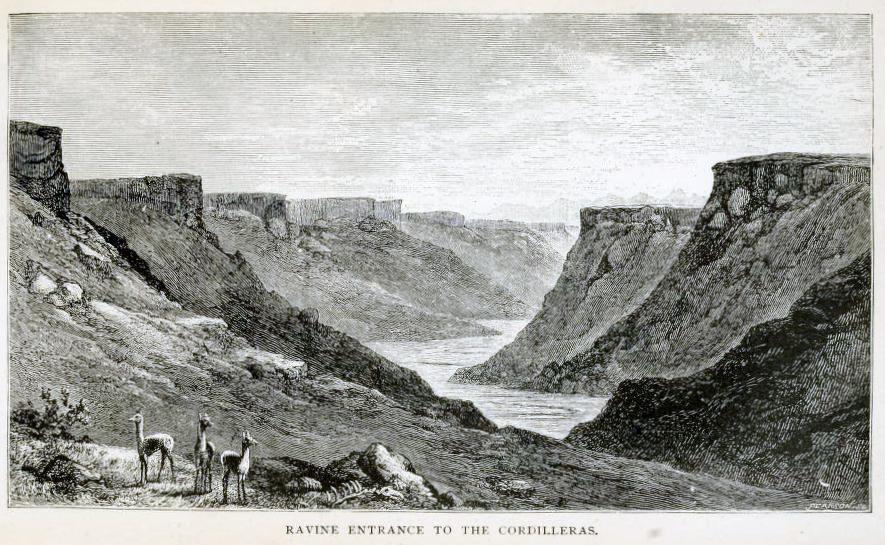

Shortly after the birth of her second son, Dixie, along with her husband and brother, travelled to Patagonia. She sought ‘to flee from the strict confines of polite Victorian society,’ and relished the opportunity to explore unfamiliar and challenging terrain. Her vivid depiction of the experience, Across Patagonia, was published in 1880 and became a bestseller. Inquisitive and self-assured, Dixie later wrote to Charles Darwin to offer her observations on the tuco-tuco, described by Darwin in his Journal of Researches and witnessed by Dixie while in Patagonia. Though Darwin had written of the tuco-tuco as rarely ever venturing above ground, Dixie informed him that ‘tho’ this may be the usual habits of the tucutuco… there are exceptions’:

In 1879, I spent 6 months on the Pampas and in the Cordillera Mountains of Southern Patagonia and during my wanderings over the plains I have had occasion to notice in places tenanted by the tucutuco, as many as five or six of these little animals at a time outside their burrows. This was on moonlight nights, and I cld. not possibly be mistaken as they wld. frequently come within a yard of the spot on which I was lying.

Dixie later sent Darwin a copy of Across Patagonia, which remains the Cambridge University Library today. Her impulse to adventure did not abate, and in 1881, she became the first woman officially appointed as a war correspondent for a British newspaper when she was sent to South Africa by the Morning Post to cover the Anglo-Zulu War.

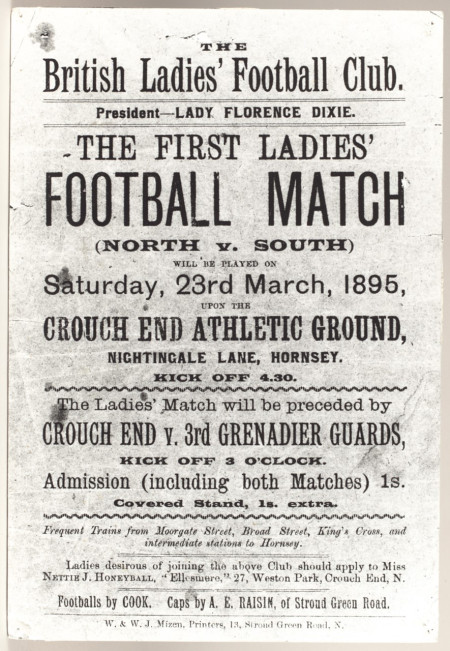

As suggested by her own unwillingness to conform to the strictures of Victorian womanhood, Dixie was passionate about the emancipation of women. Her 1890 novel Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900, depicted a feminist utopia, in which women were the social and political equals of men. In addition to winning the vote, Dixie advocated for women’s rights in all spheres of life. At its formation in 1895, she was the first president of the British Ladies’ Football Club, arguing:

There is no reason why football should not be played by women, and played well too, provided they dress rationally and relegate to limbo the straitjacket attire in which fashion delights to attire them.

Dixie was also forthright in her condemnation of the role of religion in oppressing women, and restricting their rights. In Towards Freedom, published in 1904 in the Agnostic Annual, she issued ‘an appeal to thoughtful men and women’, arguing that the teachings of Christianity sanctioned and ensured inequality between the sexes. Taking aim at the biblical tale of Eve as created from Adam’s rib, Dixie declared:

Religion says this is the law of God; I say it is that of man. Superstition declares it to be a divine ordinance; I maintain it is a barbaric one. Superstition and barbaric law go hand in hand. It is the former which creates the latter.

Dixie’s arguments recall those of Zona Vallance, inaugural secretary of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), who wrote that increased scientific understanding should enable society to shed such ideas of god-ordained hierarchy. This led Vallance to active involvement in the Moral Instruction League, which sought to remove theological teaching in schools. Dixie herself challenged the lack of power given to women in deciding what their children were taught:

Unbelievers such as I must acquiesce in the curriculum of superstition being taught to children they have born, if, peradventure, the father of those children so wills it.

Like Vallance, Dixie’s feminism was closely bound to her humanism, and both were fired by a sense of legal and social injustice consolidated by religious institutions.

Lady Florence Dixie died in 1905, aged just 50.

Those who desire to see a reign of love take the place of one just the reverse, desire humanity to face the truth and build upon it a sane religion and sane laws, whose composition shall contain true love, in which real justice, kindness, mercy, and fair play to all are alone embowered.

Lady Florence Dixie, Towards Freedom, 1904

Lady Florence Dixie was fearless in her pursuit of adventure, justice, and women’s emancipation. As is the case for many like her, however, much less has been made of her forthright unbelief, and eloquent challenges to superstition. Following her death, the Ethical Record printed a short obituary noting this omission. They observed:

a chorus of liberal if discriminate praise for her fearlessness and warmth of heart, as well as for her tumultuous talents. Justice was done to her strenuous advocacy of freedom for women, her hatred of all oppression and fiery denunciation of blood sports. But, for the most part, her heterodoxy in religion was ignored, or hinted at as an eccentricity.

Dixie’s humanism was central to her outrage at inequality, as well as to her active efforts towards securing a society which placed reason, justice, and kindness at its heart. In striving for an inclusive, rational, and compassionate world, she took up many of the challenges still at the centre of Humanists UK’s work today.

Florence Dixie is one of four humanist women featured in a set of Humanist Heritage stories and activities for schools: Think for Yourself, Act for Everyone.

Object: to provide an ‘open forum’ for the fearless consideration of modern problems relating to ethics, sociology, education, political theory, […]

…the smallest experience is sufficient to convince that it is more pleasing, to be at peace than at enmity with […]

The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery primarily located in London but with various satellite outstations located elsewhere in […]

Emilie Holyoake-Marsh, daughter of George Jacob Holyoake, was an activist for worker’s rights and women’s suffrage; an advocate of co-operation, […]