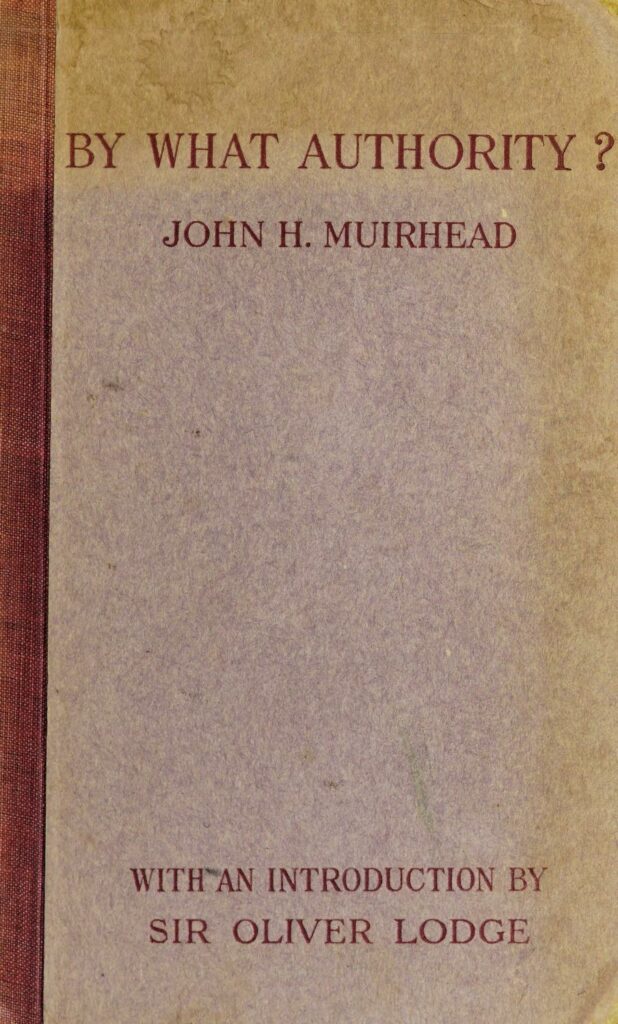

As The Times stated in John Muirhead’s obituary, the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905-9, which was set up by Parliament to investigate how the Poor Law system should be changed, gave him another ‘concrete chance to apply philosophy to life’. Muirhead points out that with Poor Laws remaining largely unchanged since the reforms of 1834, this review was urgently needed. In a series of articles, originally published in the Birmingham Daily Post, and later compiled into a book entitled By what authority?, Muirhead set out to contrast and criticise the proposals in a non-controversial spirit, and to suggest how those he regarded as valuable and workable might be incorporated into a comprehensive system of Poor Law and Industrial reform, on which all political parties might unite. Amongst his conclusions, Muirhead suggested that County Councils should be responsible for the administration, and that measures should be taken to combat poverty ‘at source’. His ideas to achieve this included increasing the mobility of labour through the institution and inter-connection of Labour Exchanges, increasing the provision of training, and regulating adult female and child employment. Furthermore, he advocated that the school age should be raised to ‘reduce the adverse influences of the streets or of unregulated homes and workshops’. He goes on to assert that whilst the report stresses the extent to which sickness and disease cause poverty, there is too little emphasis on the opposite position, poverty causing disease’. Legislators, he argues, ‘shut their eyes… to the extent to which disease is caused by remediable incidents in the workman’s life—too little food, air, and warmth, too much labour and worry’. These are powerful arguments, put forward by a man who is clearly in touch with the plight of the poor, and interestingly, his suggestions were largely adopted by later administrations.