Much of history isn’t hard fact: it’s a mass of contradicting, often mutually hostile narratives, a cacophony of competing voices, all clashing wildly.

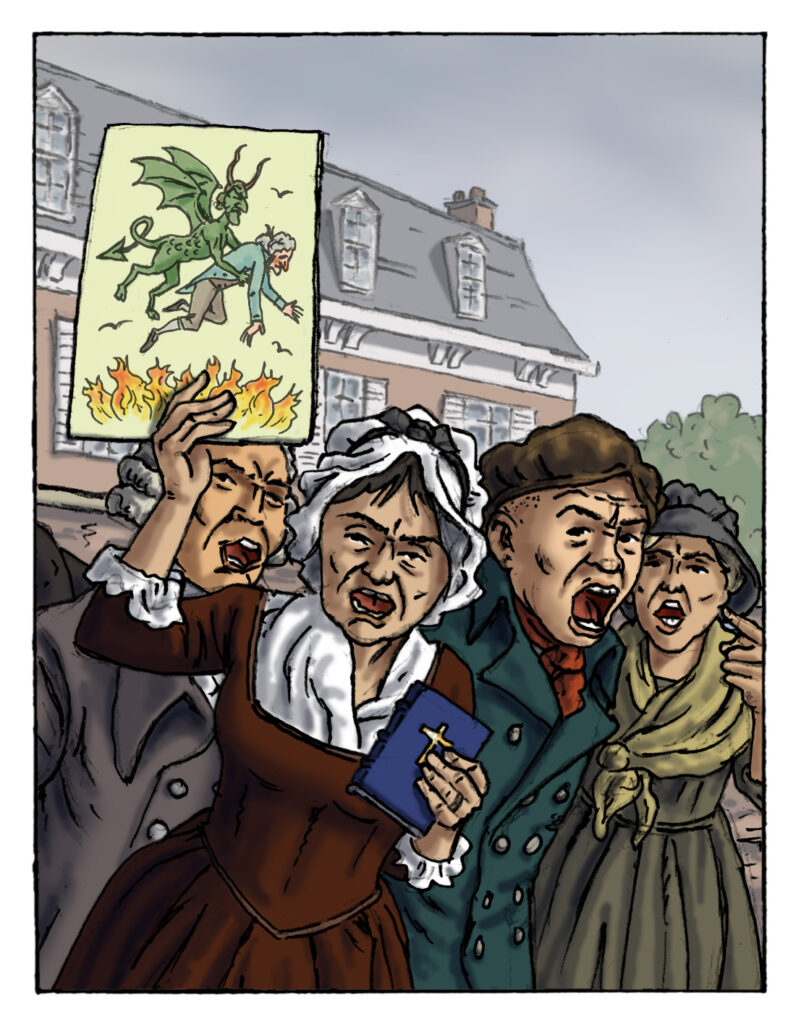

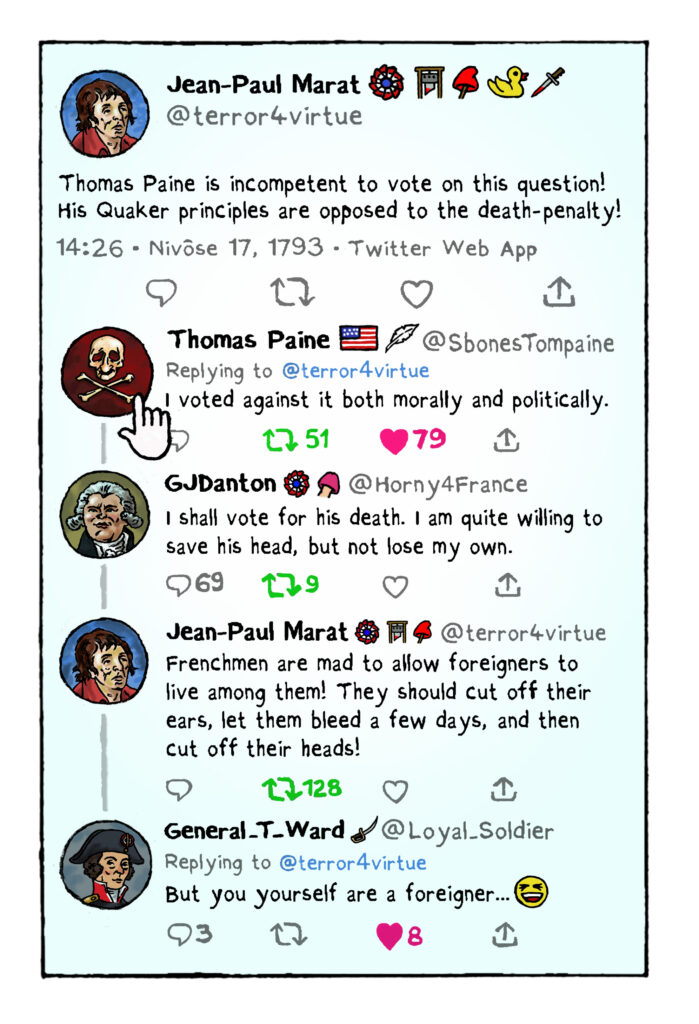

And so bringing a figure as contested as Thomas Paine back to life, in a graphic novel format, in a genuinely authentic, truthful way, was a fascinating challenge. Huge swathes of the historical narrative about him can’t be trusted: he was battered by wave after wave of hostile propaganda during and after his lifetime, in a way that feels strikingly familiar in the era of hysterical social media vilifications. Several of his biographers were hostile, and funded by his establishment enemies. The most devious of them, George Chalmers, using the pseudonym ‘Francis Oldys’, slyly coated his attacks in a veneer of affability, and to this day is the main source of much of what we think we know about his youth. Moncure Daniel Conway‘s biography The Life of Thomas Paine was written to try and counter such malicious and underhand propaganda.