Ethics really ought to have something to do with life. Ethics ought to tell you how to be good or happy, that is, if you want to be; or why it is impossible to be either good or happy; or why, though it is possible to be both good and happy, it is not possible to tell you how to be either. In short… the conclusions of Ethics ought to have some relation to the business of living.

C. E. M. Joad, Common Sense Ethics (1921)

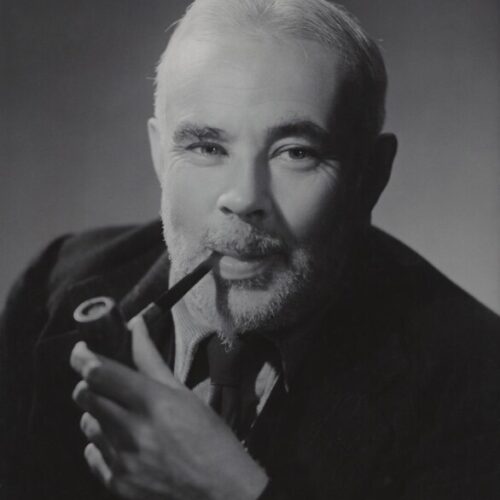

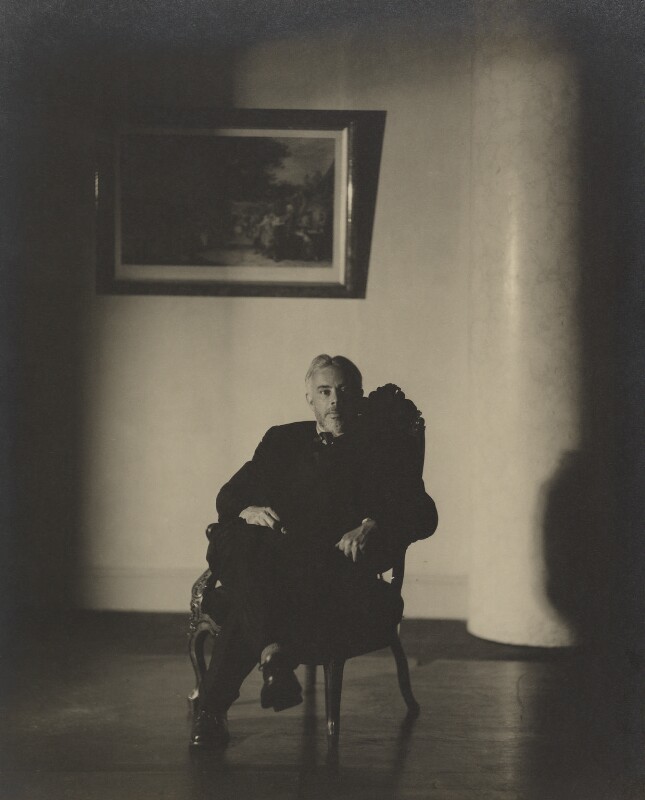

C. E. M. Joad was a prominent British philosopher, author, broadcaster, and public intellectual known for a career spent defending rationalist ideals. A flawed human being, with dismissive views of women and a character which led many (Bertrand Russell included) to express their dislike for him, Joad was nevertheless a very influential public figure during the 20th century, and a popular expounder of rationalist and progressive ideas.

Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad was born on 12 August 1891 in Durham. The family later moved to Southampton, but Joad attended the Dragon School, Oxford, and Blundell’s School, Tiverton, before gaining a first in literae humaniores from Balliol College, Oxford. It was during his time at university that Joad shifted from a Christian to a firmly rationalist outlook, going on to become a staunch advocate of humanism, advocating for a rational, ethical worldview rooted in human experience rather than divine revelation. It was also during these years that Joad developed his socialist political ideals, joining the Fabian Society in 1912. On graduating in 1914, he entered the civil service.

The outbreak of the First World War cemented Joad’s belief in the enduring need for the guiding principles of reason, rationality, and mutual responsibility. He advocated a practical philosophy, including in key publications in the years following the war, such as Common Sense Ethics (1921) and Common Sense Theology (1922). In 1930, he became head of philosophy at Birkbeck College, University of London, continuing to publish influential and accessible works like Guide to Modern Thought (1933) and Guide to Philosophy (1936). One of his works, Liberty To-day (1938), formed part of the Rationalist Press Association’s influential Thinker’s Library.

Joad’s emphasis on a practical philosophy was embodied in his support of a range of progressive organisations, including the National Peace Council, the Civil Liberties Union, and the Federation of Progressive Societies and Individuals (later the Progressive League). He expressed his belief in the possibility of a radically changed world in The Testament of Joad (1937), writing:

if I am right in thinking that there is no fundamental and incurable wickedness in human beings, if it is not fantastically optimistic in the light of their history to suppose them rational and teachable, there is no reason why we should not get a world without war, a world of material prosperity brought within reach of all, a world in which government has been reduced to an administrative mechanism for the transaction of the community’s public business. Such a world I still believe to be achievable.

It was during the 1940s that Joad became a household name, beamed into homes via the newly launched BBC radio programme Any Questions?, renamed the Brains Trust the following year. First broadcast on 1 January 1941, the show saw a panel of thinkers respond to listeners’ questions. Humanist philosopher A. J. Ayer wrote:

In its original form, the Brains Trust was a weekly programme, put out on the wireless, and commanding a large audience during the war. It was a panel consisting almost invariably of the same three persons, discussing a series of questions supposed to be chosen by the BBC producer from a stock of questions sent in by the listening public. These persons were C. E. M. Joad, playing the part of a philosopher, Julian Huxley, functioning as a scientific polymath, and Commander Campbell, a retired naval officer, injecting a note of bluff common sense. They made an excellent combination. Whatever his defects, Joad was a quick-witted and lucid speaker; he was not required to probe deeply into philosophical problems, and his giving the impression that the philosopher’s stock response to any but the most simple factual question was to say ‘it depends on what you mean by’ whatever it might be was not intolerably misleading.

A.J. Ayer, More of my Life (1985)

During the last years of his life, Joad had a very public fall from grace following a 1948 conviction for fare dodging on the Waterloo–Exeter train, which saw him ousted from the Brains Trust. A year before his death, he published The Recovery of Belief (1952), in which this once die-hard rationalist embraced the Church of England and described himself as a ‘diffident and halting Christian’. This move dismayed many of his freethinking friends, and affected his legacy among humanists. Joad died of cancer at his Hampstead home on 9 April 1953.

I have tried to explain why I have found religious belief difficult to embrace and faith hard to come by. I believe myself in this respect to be not untypical.

C. E. M. Joad, The Recovery of Belief (1952)

In an obituary for Joad, the South Place Ethical Society’s Ethical Record tried to do justice to ‘a man of many gifts and abounding energy who achieved several reputations’. While marvelling at his Brains Trust legacy as ‘a writer and college lecturer addressing, week by week, an audience of millions, offering a demonstration of extreme readiness in dealing with the problems of life’, they bemoaned his ‘contempt for the mind of woman’, which had made him an unpopular speaker at Conway Hall; ‘his outspoken anti-feminism could not fail to provoke complaint’. He had, however, been an inspiration and advisor to many: an activist shaped by figures like Shaw, Wells, and Russell. As Jason Tomes concluded in his entry for Joad in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

Cyril Joad was an outstanding educator, a tireless proponent of ‘progressive’ causes, and one of the best-known broadcasters of the 1940s. His religious conversion alienated radical agnostics who might otherwise have kept his reputation alive.

Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

‘C. E. M. Joad’ in the Ethical Record, May 1953

Works by C. E. M. Joad | Internet Archive

Main image: Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad by Bassano Ltd., 2 November 1944 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Humanism is a philosophy – one which gives us a coherent stance for living. We believe the humanist approach to […]

I cling to my tiny philosophy: to hug the present moment. Virginia Woolf, diary entry, 31 January 1940 Virginia Woolf […]

Those of us who can look back over the last thirty years will not fail to recall Mrs. Lidstone’s friendliness […]

My chosen ground Inscription on the John Hewitt Cairn John Harold Hewitt (1907-1987) was the most significant Ulster poet to […]