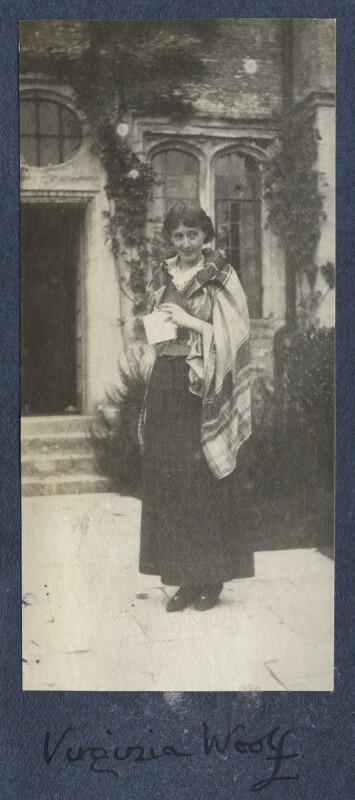

I cling to my tiny philosophy: to hug the present moment.

Virginia Woolf, diary entry, 31 January 1940

Virginia Woolf was an innovative and empathic writer, who gave new expression to the experience of being alive and helped to shape the modern novel. As the daughter of two forthright non-believers, she was also a second generation humanist: her father Leslie Stephen being a founding figure in the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), and her mother Julia Stephen the author of a powerful defence of the agnostic woman. A novelist, essayist, critic, diarist, and biographer, Woolf was a tireless writer, whose works explored ordinary life’s ‘moments of being’, and celebrated the beauty of the everyday.

I dig out beautiful caves behind my characters; I think that gives exactly what I want; humanity, humour, depth.

Virginia Woolf, 30 August 1923

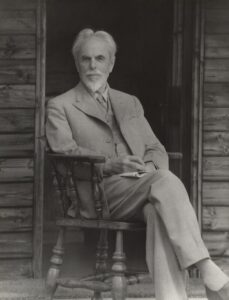

Adeline Virginia Stephen was born at 22 Hyde Park Gate, London into the social and intellectual elite of Victorian England or, as she herself wrote, ‘a very communicative, literate, letter writing, visiting, articulate, late nineteenth century world’. Her parents were Julia (née Jackson) and Leslie Stephen, both of whom had been widowed. Virginia was educated at home by her father, as well as by herself, with a rigorous devotion to reading which continued throughout her life. Leslie Stephen, the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography, emphasised precision and discrimination in writing, this ideal of conveying what was most important in as few words as possible becoming central to his daughter’s own work. Julia Stephen was a model, writer, and freethinker, who had been initially drawn to her husband on account of his writings on agnosticism; a position she shared. As Sybil Oldfield has written:

It is strange but true that had not Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth found a bond in atheism, there would have been no Virginia Woolf.

Virginia Woolf inherited the humanism of her parents and, believing in neither God nor afterlife, emphasised instead the primacy of the present moment. Like Mrs Dalloway (from Woolf’s novel of 1925), hers was an ‘atheist’s religion of doing good for the sake of goodness.’ Accepting that with death she would ‘cease completely’, Clarissa Dalloway anticipated her afterlife as being in the memories of others:

laid out like a mist between the people she knew best, who lifted her on their branches as she had seen the trees lift the mist.

A sense of life’s fragility – and the ongoing resonances of those who have died – was emphasised by the deaths of Virginia’s mother, half-sister Stella, father, and elder brother Thoby between 1895-1906.

In 1912, aged 30, Virginia Stephen married Leonard Woolf, and the pair continued to cultivate the tight-knit circle known as the Bloomsbury Group. Bloomsbury was an LGBT-inclusive network of friends and lovers that celebrated sexual equality and freedom, feeling that every person had the right to live and love in the way they chose. This original set included Vanessa and Clive Bell, biographer Lytton Strachey, artists Roger Fry and Duncan Grant, novelist E.M. Forster, and economist John Maynard Keynes. The group consciously eschewed the rigid strictures of the Victorian world into which they had been born, adopting a humanist worldview which emphasised freedom of thought and intellectual discovery. In 1917, the Woolfs established the Hogarth Press, through which they published the works of some of the era’s most influential writers. Among them were Forster and Keynes, T.S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, and Sigmund Freud.

Virginia Woolf’s own first novel, The Voyage Out, was published in 1915, and her second, Night and Day, in 1919. She also wrote essays and stories, embodying her belief in the significance of the everyday, and the possibilities of presenting human consciousness anew. Woolf argued for the momentousness of ‘moments of being’; those brief sparks of introspection and discovery inherent in even the most ordinary existence. As Lyndall Gordon has written, modernist writers (among whom Woolf was a leading figure), dispensed with Victorian realism, preferring the use of symbol, suggestion, and a disrupted sense of time, giving fiction ‘the depth of poetry’. Woolf’s subsequent novels, Jacob’s Room (1922), Mrs Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927), The Waves (1931), The Years (1937), and Between the Acts (1941), all utilised a ‘stream of consciousness’ narrative style, exploring the inner lives and social conflicts of their characters.

Woolf remained a pacifist throughout the First World War, and held fast to her detestation of warfare with the onset of the Second. By 1941, she had fallen into a deep depression, the like of which she had suffered many times throughout her life. This time though, as she wrote in a note to Leonard Woolf, she feared she was ‘going mad again’, and would not recover. On the morning of Friday 28 March 1941, she drowned herself in the River Ouse, near her home at Monk’s House, Sussex.

And what is greatness? And what is smallness?

Virginia Woolf, The Art of Biography (1939)

Virginia Woolf was a visionary writer, and one of the most influential novelists of the 20th century. She was also a lifelong humanist, whose writings embody an acute sensitivity to the difficulties and possibilities of human life. In A Room of One’s Own (1929) and Three Guineas (1938), Woolf challenged the limitations placed on women in a patriarchal society, not least in the realms of writing and education, and both essays remain classics of feminist writing today. A powerful sense of injustice pervaded these works, but so too did the capacity for shrewd observation and transformative creativity which underpinned all of her writing. Woolf created a body of work which changed the landscape of the modern novel, and cultivated a circle of friends and collaborators who remain the subject of fascination and inspiration. Despite her own personal tragedies and mental ill health, as Sybil Oldfield has written:

[Woolf’s] imaginative creativity was rooted in a lifelong mourning which she did not allow to paralyse her. Instead, she transmuted her memories of her dead, through infinite effort, into life-giving words that would not die. The only immortality she could believe in.

But however little it conforms or tenders allegiance, no life worth having can be isolated from the lives of others. […]

Hilda Caroline Miall-Smith was a teacher and activist, a graduate of University College London, and a member of the London […]

Socialism emerged, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, as a humanist ideal of universal emancipation – the ideal […]

To say that “God moves in mysterious ways” is to put up a smokescreen of mystery behind which fantasy may […]