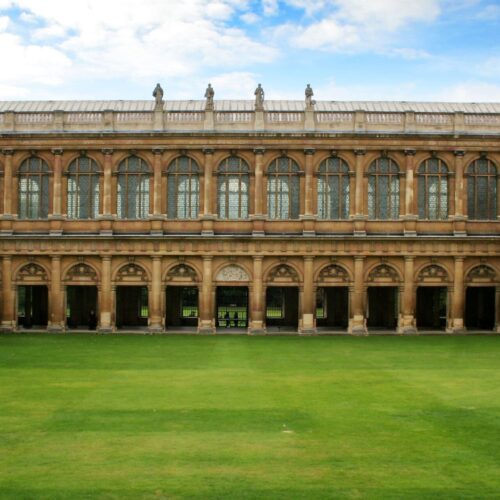

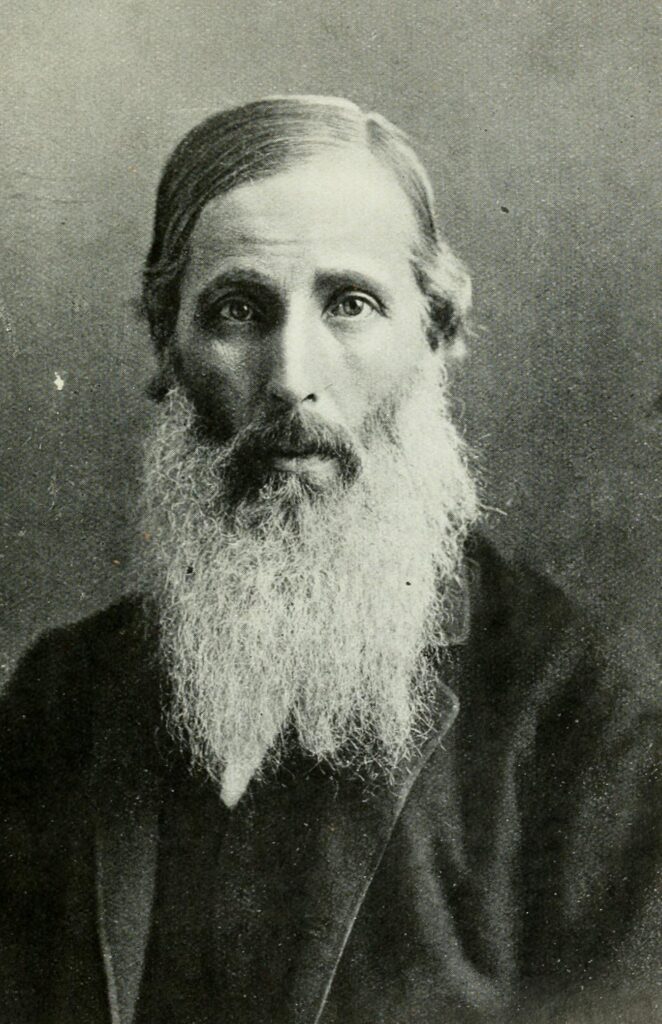

The Cambridge Ethical Society was established in 1888, inspired by the London Ethical Society (formed two years earlier). It aimed ‘to stimulate interest in ethical questions and to afford facilities for their discussion’. For its entire existence, philosopher Henry Sidgwick was its president, and among its subscribers were some of the foremost thinkers of the time, including members of the Darwin, Keynes, and Clough families.

Henry Sidgwick delivered the first address of the Cambridge Ethical Society to an audience of 70 men and women on 18 May 1888. This, and other lectures to the society, were later published as Practical Ethics (1898). The society’s activities centred on the provision of lectures (public)and the encouragement of debate around their subjects (for members). The first public lecture was delivered by historian John Robert Seeley.

The society’s organising committee included James Adam (classicist), Stanley Mordaunt Leathes (historian and civil service administrator), Augustus Edward Hough Love (mathematician and geophysicist), James Ward (psychologist and philosopher) and Sir Roland Knyvet Wilson (barrister and journalist). Its last committee, of 1896, included Emily Elizabeth Constance Jones, Elizabeth Phillips Hughes, and Eleanor Sidgwick.

The society’s preliminary report began with a motto from Goethe, ‘Gedenke zu leben’: remember to live.

In his history of the Ethical movement, Gustav Spiller notes that

the distinguished personages who composed the first Committee make it abundantly clear that the Society occupied a not unimportant position in the extra-academic life of the University and that notwithstanding its religious neutrality, it appealed intimately to a considerable number.

The Cambridge Ethical Society came to an end in 1896, though Cambridge humanist societies have of course arisen since. Spiller wrote that despite ‘high ambitions’ and ‘noble dreams’, the society’s activities were mainly limited to its programme of lectures and discussions. Nevertheless, it attracted notable thinkers and speakers from across the country, and provides an insight into the humanist tendencies of many of these.

James Adam, classicist & father of Barbara Wootton.

Miss Clough (probably Blanche Athena but could be Anne; both were non-religious)

Ellen Wordsworth Darwin (nee Crofts), academic and lecturer.

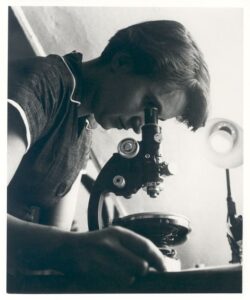

Francis Darwin, botanist & son of Charles.

Alice Gardner, historian.

Elizabeth Phillips Hughes, scholar, teacher, first principal of the Cambridge Training College for Women.

Emily Elizabeth Constance Jones, philosopher and educator.

John Neville Keynes, economist & father of John Maynard Keynes.

Augustus Edward Hough Love, mathematician.

Harris Rackham, classicist, translator, husband of Clara Rackham and brother of Arthur Rackham.

John Robert Seeley, historian and classicist.

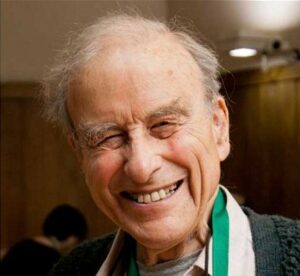

Harry Stopes-Roe was one of the most tireless and dedicated humanist campaigners of the 20th century. Son of the influential […]

Those who, like myself, are in communication with the advanced thought and thinkers throughout the world know that hundreds —nay, […]

I agree that faith is essential to success in life (success of any sort) but I do not accept your […]

Jennie Lee (also known as Baroness Lee of Asheridge) was a Scottish politician and journalist, known for her upfront orating […]