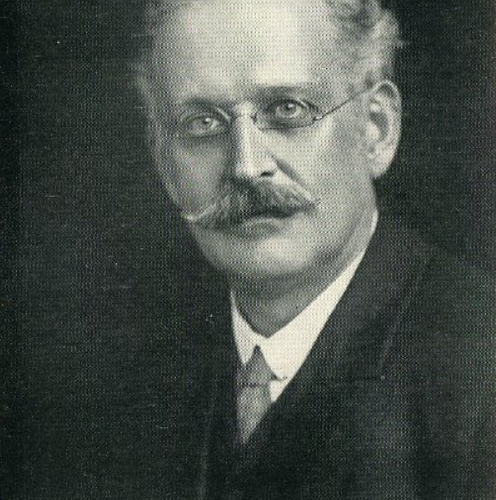

Charles Albert Watts was a lifelong promoter of rationalism, and the founder in 1885 of Watts’s Literary Guide, still published today as New Humanist magazine. It was in these pages that the obituary reproduced below was first published, written by another stalwart of the movement, Adam Gowans Whyte. It emphasises the course of Charles Albert Watts’ life: born the son of prominent secularist Charles Watts, apprenticed into freethought publishing before he had reached his teens, and subsequently a pioneer of making major scientific and philosophical works accessible and affordable for the reading public. In doing so, Watts helped blaze a trail for a freer press, and brought rationalist, humanist, and freethinking ideas well and truly into the public sphere.

From: The Literary Guide, July 1946

EDITOR OF THE LITERARY GUIDE AND PRINCIPAL FOUNDER OF THE R.P.A.

Both by heredity and early environment Charles A. Watts had, as it were, been predestined for the career to which he devoted his energies and talents for over seventy years.

CHARLES ALBERT WATTS was, in the words of a lifelong friend and co-worker, F. J. Gould, “a quite illustrious example of a single-minded enthusiasm guiding life from adolescence to old age.” Both by heredity and early environment Charles A. Watts had, as it were, been predestined for the career to which he devoted his energies and talents for over seventy years.

His father, Charles Watts, born in 1836, was the son of a Wesleyan Minister, and at an early age had been converted to Freethought by Southwell and G. J. Holyoake. From 1864 to 1877 he served as sub-editor of Bradlaugh’s National Reformer. Later he founded and edited a journal of his own, The Secular Review, and after five years of Freethought lecturing in Canada he returned to England and continued, until his death in 1906, to lecture in all parts of the country. His distinguishing quality as a lecturer was his ability to discuss the credibility of Christianity and of religion in general without rousing antagonism among even the most orthodox members of his audience. On numerous occasions he debated fundamental questions with clergymen, and invariably his opponents remained his friends. Both as parent and as exemplar he bequeathed to his son a faith in calm and informed Reason as the supreme guide in thought and endeavour.

When Charles Albert was approaching his twelfth birthday, he was apprenticed to Austin Holyoake at No. 17 Johnson’s Court, Fleet Street, for many years the recognized headquarters of the Freethought Movement.

When—in May, 1870—Charles Albert was approaching his twelfth birthday, he was apprenticed to Austin Holyoake at No. 17 Johnson’s Court, Fleet Street, for many years the recognized headquarters of the Freethought Movement. Austin Holyoake, the brother of George Jacob Holyoake, was then, in addition to sharing the duties of sub-editor of The National Reformer with Charles Watts, a printer and publisher; all the works of Bradlaugh had emanated from that narrow four-storeyed building of old brick. The apprentice’s working hours were from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m, on five days of the week and from 8 to 6 on Saturday; during the first year he had one shilling per week “good conduct” money, and for the second year his wages were six shillings per week, rising by two shillings per week each year during the seven years of apprenticeship.

There were, however, other rewards for the long and arduous hours. From Austin Holyoake—whom he described later as the most competent of teachers—he acquired an intimate knowledge of letterpress printing and of the preparation of journals and books for the press. From his contacts with the leading Freethinkers of that day he gained many friendships and much inspiration. As reading-boy, Charles Albert was brought into close touch with James Thomson (“B.V.”), who was press-reader to the firm; Thomson took great pains to awaken the boy’s interest in literature and proved himself—as he always did, especially to the younger generation, before the tragic cloud darkened his life—a gay and delightful companion. Bradlaugh visited No. 17 regularly twice a week; Annie Besant was seen from time to time; G. J. Holyoake took a fatherly interest in the boy; and indeed everyone associated with Freethought activity became a familiar figure.

In 1884 he issued the first volume of The Agnostic Annual (which developed into The Rationalist Annual of the present day) and also projected a sixpenny monthly under the title of The Agnostic... the latter project was withdrawn, and in its place the young publisher founded Watts’s Literary Guide, as a means of popularizing the firm’s publications and also of propagating Freethought.

When Austin Holyoake died his business was taken over by Charles Watts, who continued to print and publish The National Reformer and to publish Bradlaugh’s pamphlets and books. On his departure for Canada the management of the firm devolved upon Charles Albert, who, although still in his teens, soon began to initiate publishing ventures of his own. In 1884 he issued the first volume of The Agnostic Annual (which developed into The Rationalist Annual of the present day) and also projected a sixpenny monthly under the title of The Agnostic. At the instance of the proprietor of a weekly publication—The Agnostic Journal—the latter project was withdrawn, and in its place the young publisher founded Watts’s Literary Guide, as a means of popularizing the firm’s publications and also of propagating Freethought. Beginning as a modest sheet of eight pages, the venture was an immediate success; in a little over a year it had to be enlarged, and it survives to-day as The Literary Guide.

These early efforts were a remarkable testimony to the courage and skill of a boy who had recently emerged from his apprenticeship.

These early efforts were a remarkable testimony to the courage and skill of a boy who had recently emerged from his apprenticeship. He possessed no capital and no direct means of raising it. His sole asset, apart from his own abilities, was his father’s personality. In later Iife he frequently told his father that “though you were unable to aid me financially in any way, you transferred to me a record that enabled me to get credit to an unprecedented extent from firms with which you dealt.” With no other Security than his family name for integrity, Charles Albert was, strange as it may appear nowadays, able to obtain a loan from a bank to provide printing equipment.

He soon realized, however, the need for a fundamental change in the financial organization of heretical propaganda. During his years of apprenticeship he had seen more than one publishing scheme, launched with high hopes and meagre resources, eventually succumb under the double difficulty of lack of capital and the persistent boycott exercised, by the book and periodical distributing trade, on heretical literature. One phase of the problem had already been tackled by the circulation of the Guide, which afforded direct contact with at least a section of the potential public for liberal works on religion and philosophy. But the Guide, though a useful entering wedge, was not enough in itself. Some method of establishing the Movement on a permanent and progressive basis was required, and Charles Albert set to work drawing up plans and putting them into effect.

Three years after the Guide was founded the editor appealed for £1,000 “at least” to establish a Propagandist Press Fund. The object of the Fund was two-fold: first, to disseminate Freethought literature; second, to secure, by agitation, liberty of bequest for Freethought purposes.

How ably he planned, and how skilfully he administered the execution of his scheme, the history of Rationalism bears eloquent witness.

Three years after the Guide was founded the editor appealed for £1,000 “at least” to establish a Propagandist Press Fund. The object of the Fund was two-fold: first, to disseminate Freethought literature; second, to secure, by agitation, liberty of bequest for Freethought purposes. Of these two purposes the second was much the more significant. As the law stood in those days, property bequeathed for anti-theological purposes could be confiscated. So long as this condition persisted it was clearly impossible to provide any stable foundation for Freethought propaganda. Thus it was quite in order that, out of the money contributed to the Fund, a substantial amount was handed to the Liberty of Bequest Committee, which was working for a reform of the law. Eventually the reform was achieved, removing one of the last relics of religious bigotry surviving in our statutes.

The introduction of the word “Rationalist,” instead of the traditional terms “Freethinker” and “Agnostic,” was due largely to F. J. Gould, and it gave expression to the broader and more constructive outlook which developed towards the close of the century.

Meanwhile the Fund continued with the dissemination of Freethought literature. Early in 1893 it adopted the more appropriate title of the Rationalist Press Committee. The introduction of the word “Rationalist,” instead of the traditional terms “Freethinker” and “Agnostic,” was due largely to F. J. Gould, and it gave expression to the broader and more constructive outlook which developed towards the close of the century. Much excellent work was done by the Committee, with the aid of subscriptions and donations, but the founder and manager was fully aware that the constitution of the Committee was inadequate for the developments he had in view. After consultation with the leading Rationalists of the time, and after prolonged consideration of the legal and other aspects, Mr. Watts saw his vision realized by the formation, on May 26, 1899, of the Rationalist Press Association Limited. G. J. Holyoake was chairman at the inaugural meeting, and the other signatories to the memorandum were Charles Albert Watts, Charles E. Hooper (the first secretary), A. Gowans Whyte, John S. Dryden, R. B. Anderson, Charles T. Gorham (later secretary), and Dr. Clair J. Grece.

The progress of the R.P.A. was his unfailing preoccupation, and to its service he devoted qualities of forethought, initiative, organizing power, and leadership which would undoubtedly have brought him fame and fortune had they been expended in a less arduous and more popular cause.

Many years later when Gould had completed the history of the Rationalist Press Association, published under the title of The Pioneers of Johnson’s Court, he handed the manuscript to Watts, who studied it intently and then observed: “This is my life”. “These four simple words might,” Gould remarked, “be written in shining letters over the door of the R.P.A. as an exact record of the founder’s career.” The progress of the R.P.A. was his unfailing preoccupation, and to its service he devoted qualities of forethought, initiative, organizing power, and leadership which would undoubtedly have brought him fame and fortune had they been expended in a less arduous and more popular cause. Neither fame nor fortune, however, had any attractions for him. Once the foundations of his life-work were laid, he had created the task that lay nearest to his heart’s desire and offered the fullest scope, in the happiest of environments, for all his faculties.

If any one of these faculties deserves to be singled out as of supreme value, especially in the early formative years of the enterprise, it was his power of making sympathetic friends. Spencer, Leslie Stephen, Huxley, Clifford, Edward Clodd, Samuel Laing, and other great men gave him their confidence and co-operation without reserve. Others who could help only by providing the sinews of war were equally ready. Many of them regarded Mr. Watts as the sole embodiment of the Rationalist cause, and their trust in him was so complete that they offered their contributions to him personally, to spend as he pleased, preferring the man they knew to the organization that was still but a name to them. In such cases the money was passed into the capital fund of the Association frequently with a verbal guarantee—still scrupulously observed—that only the interest should be drawn upon for current needs. Mr. Watts saw in each sum, large or small, an additional protection against the vicissitudes which had broken so many promising ventures associated with Johnson’s Court.

In order to meet, as far as possible, the boycott of the distributing trade, he organized the Association on the lines of what became known later as a “book club,” each member receiving books to the value of his subscription… Thanks to this simple arrangement, readers interested in Rationalism were made independent of booksellers who were afraid to display heretical literature or were reluctant to deal in so dangerous a commodity.

The supporters of the Movement were, of course not moved entirely by the sense of Mr. Watts’s high integrity; they appreciated also his mastery of the problem before him. No one had a more intimate knowledge of the difficulties, and no one showed more ingenuity and sound business sense in devising means of overcoming them. In order to meet, as far as possible, the boycott of the distributing trade, he organized the Association on the lines of what became known later as a “book club,” each member receiving books to the value of his subscription. As the membership grew, this plan provided a firm nucleus of sales which enabled the Association to maintain an increasing output of Rationalist books at a moderate price while the concomitant growth of donations permitted the Association to face the risk of loss on more expensive works of exceptional propaganda value but with limited prospects of sale outside the narrow range of specialist students of religion.

Thanks to this simple arrangement, readers interested in Rationalism were made independent of booksellers who were afraid to display heretical literature or were reluctant to deal in so dangerous a commodity. The development of this novel machinery was greatly assisted by the circulation of The Literary Guide; indeed it was the Guide which made its initiation and growth possible.

His ultimate aim was to see the Association’s publications taking their place as a matter of course alongside others in bookshops, and bookstalls. Towards this end he took a step, while the R.P.A. was still in its infancy, of the most daring and indeed revolutionary character.

Mr. Watts fully realized, however, that it was not enough to short-circuit the boycott by organizing a Rationalist book club. His ultimate aim was to see the Association’s publications taking their place as a matter of course alongside others in bookshops, and bookstalls. Towards this end he took a step, while the R.P.A. was still in its infancy, of the most daring and indeed revolutionary character.

In those days the public had been accustomed to cheap reprints of novels. The volumes were closely printed, bound in paper, and sold at sixpence. Experience had amply proved that such reprints brought additional revenue to publishers and authors, but the firm conviction of the publishing trade was that only fictional works of exceptional popularity could ensure the large circulation necessary to bring the unit cost of production low enough for profitable sale at so low a price. This conviction Mr. Watts challenged by proposing to publish cheap reprints of books by leading Rationalists such as Huxley, Darwin, Tyndall, and Clodd. In most cases permission for a sixpenny edition had to be obtained from the publishers of the original editions, and the natural reaction of almost all of these publishers was that Mr. Watts was plunging into bankruptcy. To quote his own words,

they were convinced that there was no remunerative market for serious literature at what one of them characterized as ‘almost waste-paper price.’ It is now common knowledge that they were deplorably wrong in their estimate of the intelligence of the masses. The wonderful success of our new departure quickly induced other houses to start many similar series. I need mention only one—the Home University Library, which has been a boon and a blessing to millions of readers.

Booksellers could hardly decline to sell, at sixpence, works written by eminent men and formerly stocked at normal prices.

For the first volume of the series of R.P.A. Cheap Reprints negotiations had to be conducted with Macmillan’s, and Mr. Watts has recorded, with grateful thanks, how Sir Frederick Macmillan, who never disguised his lack of faith in the Association’s efforts to popularize scientific and heterodox literature, consented to this volume appearing with the joint imprint of his firm and that of the R.P.A., thus helping to break down the prejudice then existing against the R.P.A. The reprints themselves helped to carry the process further. Booksellers could hardly decline to sell, at sixpence, works written by eminent men and formerly stocked at normal prices.

The good work was further assisted by Mr. Watts, who, as the Movement could not then maintain a special “traveller,” went on the road and exercised his genius for making friends. The buyer of one of the largest book distributing firms had such confidence in Mr. Watts’s judgment that he left it to him to decide, in the case of each new reprint, whether the initial order should be for 1,300, 2,600, or 5,200 copies.

Few of the modern readers who enjoy an ample provision of cheap and informative works on all sorts of scientific and other serious subjects are aware of the debt they owe to the courage and acumen of Mr. Watts. The R.P.A. Cheap Reprints were the ancestral prototype of the Penguins of to-day.

Few of the modern readers who enjoy an ample provision of cheap and informative works on all sorts of scientific and other serious subjects are aware of the debt they owe to the courage and acumen of Mr. Watts. The R.P.A. Cheap Reprints were the ancestral prototype of the Penguins of to-day. But the publishing adventure undertaken, at the opening of this century, in defiance of established opinion had other important consequences. It gradually undermined the boycott in the distributing trades against heretical works, and this change induced publishers in general to adopt a more receptive attitude towards unorthodox writers. At the time when Mr. Watts founded the R.P.A., authors of works which challenged accepted views on religious and associated problems had the greatest difficulty in persuading publishers to risk either their reputation or their capital by issuing such works. Nowadays, however, the majority of publishers do not reject a manuscript merely because it runs counter to the mainstream of the Christian or any other tradition. The author of an unconventional book has a far wider choice of publication than he enjoyed half a century ago. Throughout the profession and trade of English letters there is a degree of receptivity for new ideas, and a liberality of spirit, which are in strong contrast with the earlier conservatism. Within the book world, indeed, a genuine approach to freedom of expression has been attained. The pioneer work in the struggle was done by the great Freethinkers whom Charles Albert served as a boy; the culminating stages began with his great experiment in placing the classics of Freethought and modern science within easy reach of the masses.

It gradually undermined the boycott in the distributing trades against heretical works, and this change induced publishers in general to adopt a more receptive attitude towards unorthodox writers… The author of an unconventional book has a far wider choice of publication than he enjoyed half a century ago.

To that task he consecrated all his energies from early manhood onwards. During the earlier and most strenuous years he usually worked from twelve to fourteen hours a day on six days of the week and seldom rested long on the seventh, Intervals for leisure were infrequent, and as they were mainly spent in entertaining friends at his home in Cecile Park they were often the occasion of informal discussions of R.P.A. affairs. Intense as the concentration of effort was, it did not restrict his interests and sympathies in a corresponding degree. The work brought him into intimate contact with a wide circle of men and women, and it presented him with many problems, personal as well as professional, which appealed to his sensitive feelings as well as to his disciplined wisdom. Anyone in difficulties would gain from him both practical help and sage advice, but there was one type of human problem which, recurring again and again, baffled all his attempts to reach a satisfactory solution. Clergymen who had lost their faith in the doctrines they had been ordained to preach came to Johnson’s Court in search of a way out of an intolerable situation. Where they were unmarried, Mr. Watts counselled them, without reserve, to “leave all and fight for the truth as they conceived it,” but where they were married he considered that their obligations to wife and family came first and that they should remain in the Church unless they were assured of a living wage outside. On more than one occasion Mr. Watts was reproached for recommending this course, but he was convinced that the alternative would mean destitution for the clergyman’s dependents. It is only in exceptional cases that emancipated clergymen are capable of earning a reasonable living outside the Church.

The work brought him into intimate contact with a wide circle of men and women, and it presented him with many problems, personal as well as professional, which appealed to his sensitive feelings as well as to his disciplined wisdom.

Considering his early environment it is not surprising that Mr. Watts felt the stirring of literary ambitions. “In my teens,” he wrote in the Guide, “I had the effrontery to contribute occasional articles to the Freethought Press, and I was only just over twenty when I essayed to review books, with all the assurance of an expert… Fortunately, since that time I have shown due recognition of my limitations. From the day I launched The Literary Guide (in 1885) I have written little beyond my monthly jottings and similar paragraphs for other departments of the paper.”

As editor and publisher his judgment rarely erred, and his instinct for promise in a new writer was unfailing.

Behind this frank recognition of his prospects as a writer there lay a measure of regret; he would certainly have liked to be able to express his thoughts in a style which would merit his own approval, but as he had tried and found himself wanting, he cheerfully reconciled himself to producing the works of others. Here he found his true métier, and one which brought equal happiness and success. As editor and publisher his judgment rarely erred, and his instinct for promise in a new writer was unfailing. His standards in matter, form, and presentation were high, and he applied them uncompromisingly to every work submitted to him, whether the author was distinguished or was merely hoping to become so. In the earlier years he himself read every work he published—read it with meticulous care in correcting every fault, great or small. For young authors it was an invaluable discipline to have their works pass through his hands. Older authors, who were sometimes inclined to be sensitive and to regard their productions as verbally inspired, might at first resent his emendations, but in the end they usually became grateful to their competent and punctilious critic. When Mr. Watts’s blue pencil operated, it was never from merely pedantic motives or in response to any dogmatic conceptions of correct style; the corrections concerned matters of fact, unjustifiable expressions, and phrases or constructions which offended the laws of English usage by affecting clarity or cogency. The same high standards were observed in the printing and production of the volumes, with the result that every volume issued from Johnson’s Court was a credit, in both contents and typography, to the Association.

In a sense, of course, he was an autocrat, dominating the Board by his personality and his unique experience, but he was always a rational as well as a benevolent autocrat, never seeking to impose upon the Board a policy which his colleagues did not, after the fullest discussion, cordially approve.

The happy relations established between publisher and authors were reflected in those existing within the Association itself. Mr. Watts was an ideal managing director—constructive, businesslike, definite in his own well-considered views, and ready to weigh every argument. In a sense, of course, he was an autocrat, dominating the Board by his personality and his unique experience, but he was always a rational as well as a benevolent autocrat, never seeking to impose upon the Board a policy which his colleagues did not, after the fullest discussion, cordially approve. No Movement which involves the co-operation of men of diverse capacities and outlook can proceed far without arousing a conflict of wills, but in the case of the R.P.A. these incidents were rare and were generally resolved by quiet persuasion and by emphasis on the supreme criterion—the welfare of the Association. If these measures looked like proving ineffective, Mr. Watts would say: “My friend, we agree on so many things; do not let us quarrel over this.”

In his new role of observer of the work of others he proved himself as sagacious as when he himself had been in command; he gave his successors a free hand in the exercise of their responsibilities, and he was equally generous with his counsel when consulted on any issue.

At the age of seventy-one, failing health obliged Mr. Watts to retire from the active direction of the affairs of the R.P.A. and of the associated printing and publishing firm of C. A. Watts & Co. Ltd. Accordingly in March, 1930, he relinquished the post of managing director of the R.P.A. which he had held continuously since 1899, but he remained on the board as Vice-Chairman. His reluctance to rest from his labours was mitigated by the knowledge that the R.P.A. had reached a stage of stability and prosperity far beyond his most sanguine hopes in the early days of struggle and also by the confidence he felt in his son Frederick, who succeeded to the managing directorship of the R.P.A., and in his daughter Gladys (Mrs. G. M. Dixon), who gave invaluable service in the affairs of Watts & Co. He retained, however, his editorship of the Guide and never abated his keen interest in every phase of the activities of the R.P.A. In his new role of observer of the work of others he proved himself as sagacious as when he himself had been in command; he gave his successors a free hand in the exercise of their responsibilities, and he was equally generous with his counsel when consulted on any issue.

Few men have been called upon to face imminent death so often and no one could have met the recurrent challenge with greater serenity of spirit. In the final struggle, which was mercifully brief, he was fully conscious that this time he would not win through. The end had come to a long, happy, and immeasurably fruitful life.

In his retirement, therefore, Mr. Watts continued to serve the cause to which he had devoted his active life. He was fortunate, despite his physical disabilities, in retaining his mental alertness until the end. So heavy were these disabilities that, when the period of retirement began, nobody anticipated that it could last more than a few years. Time and again his illness would take a critical turn; time and again his indomitable will, allied with the devoted care bestowed upon him by his wife, carried him through the crisis. Few men have been called upon to face imminent death so often and no one could have met the recurrent challenge with greater serenity of spirit. In the final struggle, which was mercifully brief, he was fully conscious that this time he would not win through. The end had come to a long, happy, and immeasurably fruitful life.

A. G. W.

In the beginning natural philosophers tried to understand the world around them. Trying to do that they hit upon the […]

I remain an agnostic, and the practical outcome of agnosticism is that you act as though God did not exist. […]

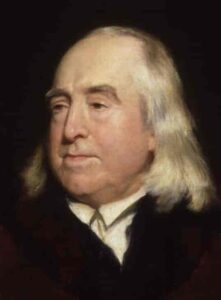

It is impossible that Theology can throw any light upon either morality or jurisprudence. Jeremy Bentham Philosopher and jurist Jeremy […]

Atheist Charles Southwell was imprisoned in Bristol Gaol for blasphemous libel in 1842. Southwell had written an article in his […]