Why not agree to differ about the questions which no one denies to be all but insoluble, and become allies in promoting morality?

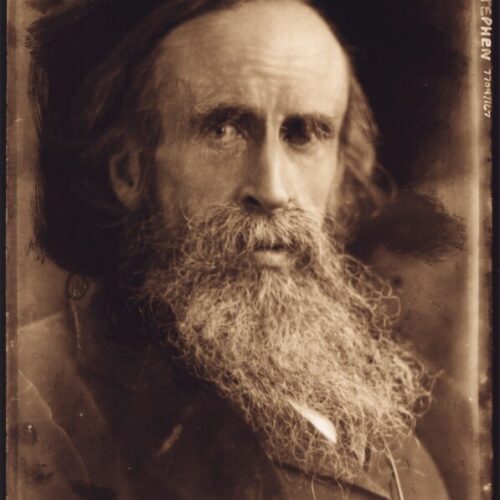

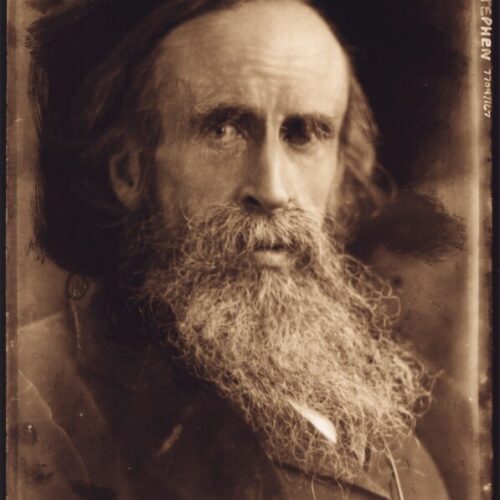

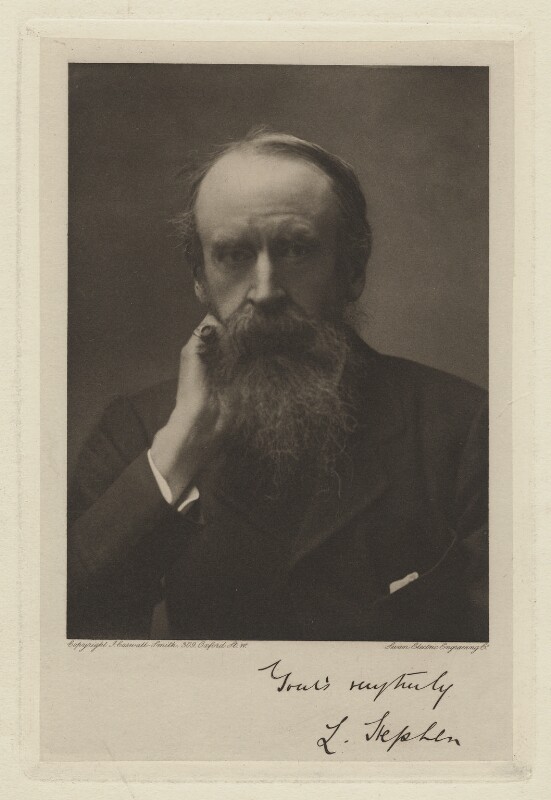

Leslie Stephen, ‘The Aims of Ethical Societies’ 1892

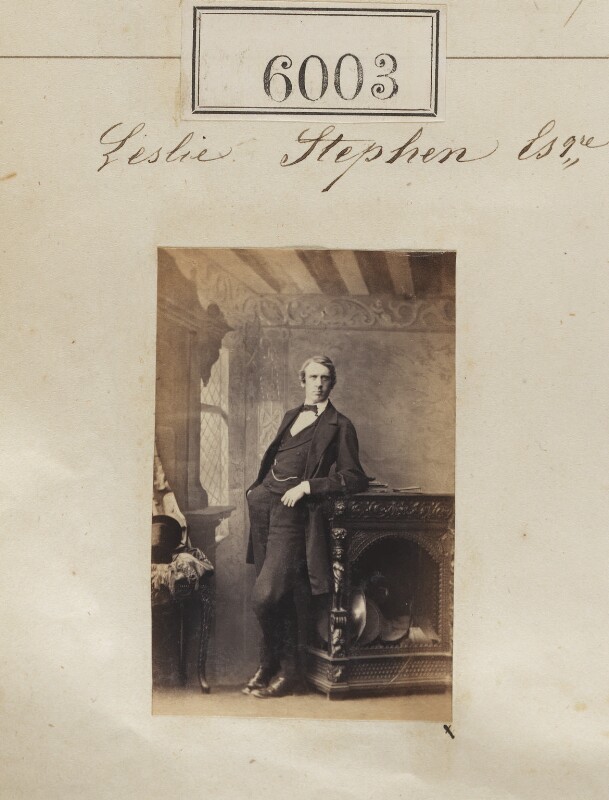

Father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, Leslie Stephen was the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography and involved in the Ethical movement from its beginnings in the UK. As a prominent agnostic, his writings on freethinking remain notable, and his influence was significant within the early organised humanist movement. In 1894, Stephen became the first President of the West London Ethical Society, which was a driving force in the 1896 formation of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK).

Leslie Stephen was born in Kensington, London on 28 November 1832. A sickly child, the family moved to Brighton in 1840 partly for his health, and later to Windsor. Stephen attended Eton College as a day boy but gained more intellectually from his freedom to read at home and the atmosphere of learning in the household. He went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he went on to become an active sportsman, gifted mathematician, and eventually a member of staff. He was a devoted walker, hiker, and mountaineer, joining the Alpine Club in 1858, of which he later became president.

Stephen’s religious scepticism began at university and grew more secure throughout his life, influenced by his literary, scientific, and philosophical reading. He formally denounced the Anglican vows he had taken in the course of his duties at Cambridge in the presence of a witness, Thomas Hardy. He would tell the West London Ethical Society in 1892 that:

…morality depends on something deeper and more permanent than any of the dogmas that have hitherto been current in the churches. It is a product of human nature, not of any of these transcendental speculations or faint survival of traditional superstitions. Morality has grown up independently of, and often in spite of, theology.

Part of the role of the ethical societies was to devote themselves to questions of ethics removed from any supernatural notions. Stephen expressed his hope ‘that such societies… may in the first place serve as centres for encouraging and popularising the full and free discussion of the great questions.’ This discussion, though, should serve a practical purpose, producing resolutions applicable to the problems of the present day: ‘after all, a philosopher can learn few things of more importance than the art of translating his doctrines into language intelligible and really instructive to the outside world.’ Both discussion and action were central to the work of the ethical societies.

Stephen officially left Cambridge in 1864, moving to 19 Porchester Square, London, to live with his mother and sister. Here, he began work as a journalist – writing for both the Saturday Review and the Pall Mall Gazette. Other contributions were to the Cornhill Magazine, Fraser’s Magazine, and the Fortnightly Review. Stephen took over as editor of the Cornhill Magazine in 1871 and held the post for 11 years. In this role, he supported the careers of a number of new or emerging writers, including Thomas Hardy (from who he commissioned Far From the Madding Crowd over the editions of 1874) and Henry James.

In 1866, Stephen married the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray, Harriet Marian (Minny). He moved into the Thackeray home at 16 Onslow Gardens, where he and Minny lived along with her elder sister. In November 1875, Minny Stephens died suddenly during pregnancy from eclampsia, her death falling on Stephens’ birthday, which from then on was no longer celebrated. Grief stricken, Stephens pursued his writing with determined focus. In addition to numerous articles, 1876 saw the publication of both his History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, and An Agnostic’s Apology.

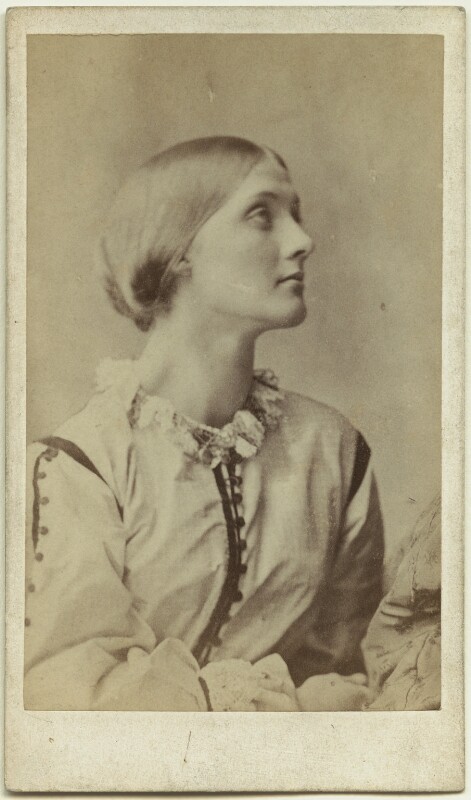

Stephen moved to 11 Hyde Park Gate in June 1876, developing a close friendship with his widowed neighbour, Julia Duckworth. Their support and affection for one another grew and in 1878 they were married. The merged families (occupying the Duckworth house at 13 Hyde Park Gate), comprised Laura Stephen, the three Duckworth children, and before long four more: Vanessa (b. 1879), Julian Thoby (b. 1880), (Adeline) Virginia (b. 1882), and Adrian Leslie (b. 1883).

Prior to beginning his longstanding editorship of the Dictionary of National Biography, Stephen – whose insightful biographical work was already acknowledged – contributed a series of works to Macmillan’s English Men of Letters series, writing the lives of Samuel Johnson, Alexander Pope, and Jonathan Swift. In 1881, Stephen undertook the newly conceived Dictionary, publishing its principal announcement in The Athenaeum. This organ was also instrumental in printing twice each year a list of proposed names for inclusion, alongside calls for suggestions and information. Stephen did not overlook the importance of featuring the lesser known, and created guidelines for entries to omit the ornamental in favour of conciseness and interest. The first volume emerged in January 1885, to great acclaim.

After illness, recuperation, and relapse, Stephen resigned his editorship in 1891. He had written that in times of increasing strain: ‘My own self-esteem is more or less involved in pushing it through’ He continued, though, as a contributor, his articles numbering 283.

Julia Stephen died suddenly in May 1895 and, once again, Stephen threw himself into writing. The result was an intimate family memoir, later published from a manuscript held by the British Library in 1977. Stephen also memorialised the character of his late wife in an Ethical Society address, published in 1896’s Social Rights and Duties, in part commending her own response to loss.

Is the world a scene of probation, in which we are to be fitted for higher spheres beyond human ken by the hearty and strenuous exertion of every faculty that we possess ? or shall we say that such action is a good in itself, which requires to be supplemented by no vision of any ulterior end?

Leslie Stephen, ‘Forgotten Benefactors’ in Social Rights and Duties (1896)

In Stephen’s writing on death and the value of life, there emerges a strongly humanist view, divorced from any belief in an afterlife beyond the resonance of our lives among those who knew us:

We are shocked by the sense of the inevitable oblivion that will hide all that we loved so well. There is, according to my experience, only one thought which is inspiring, and — if not in the vulgar sense consoling, for it admits the existence of an unspeakable calamity — points, at least, to the direction in which we may gradually achieve something like peace and hopefulness without the slightest disloyalty to the objects of our love. It is the thought which I can only express by saying that we may learn to feel as if those who had left us had yet become part of ourselves; that we have become so permeated by their influence, that we can still think of their approval and sympathy as a stimulating and elevating power, and be conscious that we are more or less carrying on their work, in their spirit.

Stephen died on 22 February 1904 and his ashes interred in Highgate Cemetery, following a funeral service at Golders Green Crematorium.

Dreams may be pleasanter for the moment than realities; but happiness must be won by adapting our lives to the realities.

Leslie Stephen, ‘An Agnostic’s Apology’ in An Agnostic’s Apology and Other Essays (1903)

Stephen actively championed the humanist Ethical movement, and lived his life according to a devotion to reason and humanity set free from any supernatural concerns. As a journalist, writer, and editor, Stephen contributed a great deal to promoting wider knowledge of individuals and their ideas through many works of biography.

Stephen’s belief in the significance of including the unsung figures of history in the Dictionary of National Biography, recalls another distinctly humanist element of his philosophy: that morality was derived not from the divine interventions of the Christian faith but instead through the aspirations of the millions ‘to discover rules of conduct and modes of conceiving the universe more congenial than the old to their better nature’. In observing examples of this, we could find hope for the ‘immortality’ of our own deeds, without the need for religious belief.

When so regarded, it seems to me, and only when so regarded, we can see in the phenomenon something which may give us solid ground for hopes of humanity, and enable us to do justice to countless obscure benefactors.

…and we may comfort ourselves, if comfort be needed, by the reflection that, though the memory may be transitory, the good done by a noble life and character may last far beyond any horizon which can be realised by our imaginations.

Leslie Stephen, ‘Forgotten Benefactors’ in Social Rights and Duties (1896)

Founded in 1905 by the prolific but largely unremembered writer Richard Dimsdale Stocker, the Brighton and Hove Ethical Society – […]

The Open University was founded in 1969 with the ambition of providing access to higher education for people who had […]

It is in fact a strength, not a weakness, of a secular morality that it must stand upon its own […]

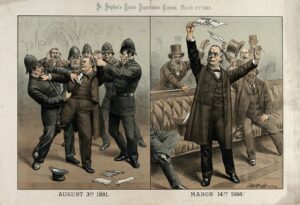

The House of Commons refused to allow his affirmation, so Bradlaugh applied to take the oath but was again refused. […]