Avoiding alike mysticism and shallow denial, he was a true Agnostic, anxious not merely to beat down error, but to build up truth.

Charles T. Gorham, ‘Death of Charles Watts’ in The Literary Guide, March 1906

Charles Watts was a writer, lecturer, editor, and publisher, whose life was spent promoting rationalism and secularism. Sub-editor for many years of the secularist National Reformer (strongly associated with Charles Bradlaugh), he also founded the Canadian freethought magazine Secular Thought, published 1887–1911. Watts’ son, Charles Albert, founded The Literary Guide (now New Humanist) in 1885, from which the obituary below is reproduced.

Originally published in The Literary Guide in March 1906, the tribute illustrates the high regard in which his friends and colleagues held the man they considered a pioneer. It is notable that the ‘secularism‘ they describe Charles Watts as playing such a key role in promoting was a philosophy synonymous with humanism today, emphasising, in Arthur B. Moss’ words, ‘the value of this life—the only life we really know of—and the importance of doing the best we can to promote the well-being of our fellows, apart altogether from the consideration of any life in the future’. Also reproduced is a description of Watts’ funeral ceremony, published in The Literary Guide in April 1906, along with tributes from members of rationalist, humanist, and religious communities.

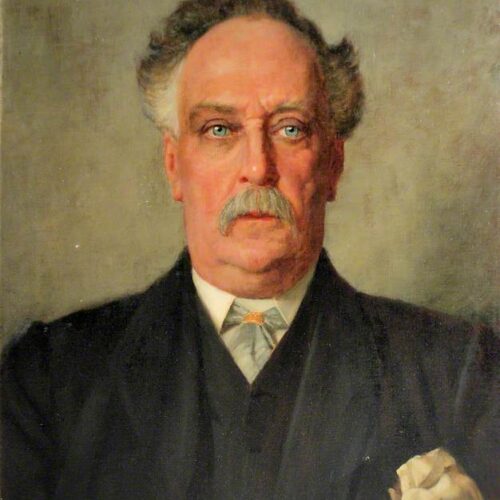

Main image: Charles Watts by Rowland Holyoake, 1904, on display in the Library of Conway Hall.

From: The Literary Guide, No. 117, 1 March 1906

We regret to announce that Mr. Charles Watts passed away on Friday evening, February 16th. He had been unconscious for more than twenty-four hours, and the end was quite peaceful.

As in the case of so many other well-known Freethinkers, his childhood was passed amid the influences of religion, but these do not seem to have been so enduring as the parents must have wished.

Charles Watts was the son of a Wesleyan minister, and was born at Bristol on February 27th, 1836, the year before Queen Victoria came to the throne. As in the case of so many other well-known Freethinkers, his childhood was passed amid the influences of religion, but these do not seem to have been so enduring as the parents must have wished. The piety of the young is seldom anything but a forced and artificial product, and the strong intellectual bent of Charles Watts enabled him to rise above an environment which, with weaker minds, often leads to a permanent atrophy of thought. At the early age of nine he joined a Mutual Improvement Society and a class for elocution, a study to which he took with a zeal that bore valuable fruit in later life. Filled with youthful ardour for the cause of temperance, he gave an address on teetotalism when no more than fourteen years old—an exploit which, if it indicated some temerity, revealed also self-reliance and moral earnestness. In another way Charles Watts showed himself able to defy prejudice. While still a lad he joined the Bristol Dramatic Society, and took part in several amateur performances. The love of the drama thus awakened never left Charles Watts; to him it was always one of the pleasures of life, and he was himself an actor of no contemptible skill.

A lecture by George Jacob Holyoake gave the final impetus to his decision, and Charles Watts became a Secularist.

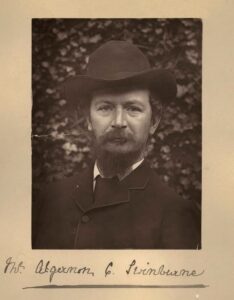

Most young men, especially those who possess earnestness and ability, have to pass through a stage of intellectual doubt and agitation, when the problems of life are presented with a crude and painful incoherence. In many the process takes an emotional turn, and issues in what is called “conversion,” a state which is as often intellectually harmful as it is morally beneficial. Mental unrest in Charles Watts resulted in a breach with the orthodox creed. Examining his religious opinions, not with the blind eye of faith, but in the clear light of reason, he became convinced that they were untenable. A lecture by George Jacob Holyoake gave the final impetus to his decision, and Charles Watts became a Secularist. The acquaintance with Mr. Holyoake was the beginning of a friendship between these Freethought leaders which lasted undimmed throughout their, lives, and Mr. Watts’s friends can recall many occasions on which he spoke of his venerated leader in terms of admiration which to others might seem almost hyperbolical.

In 1864 he joined his elder brother John in the printing business, and became sub-editor of the National Reformer… In the same year Charles Watts began the lecturing career in which he became most widely known, and in which much of his best work was accomplished.

Coming to London at the age of sixteen, Charles Watts soon became acquainted with Southwell, Cooper, and other prominent men in the Secularist movement, chief among them being Charles Bradlaugh. But while his mind was steadily growing, it was not for several years that Mr. Watts took any active share in propagandist work. In 1864 he joined his elder brother John in the printing business, and became sub-editor of the National Reformer, which was established and edited by the latter, and which for so many years valiantly upheld the banner of Freethought. In the same year Charles Watts began the lecturing career in which he became most widely known, and in which much of his best work was accomplished.

John Watts died in 1866, having expressed a wish that his brother should become editor and proprietor of the paper. Charles Watts, however, thought Bradlaugh a better man for the post, and with rare generosity gave up his right on the sole condition that he should retain his sub-editorship. This arrangement continued till 1877, and during those years Charles Watts rendered most valuable services not only to the cause represented by the National Reformer, but to Bradlaugh personally.

For many years Mr. Watts was Secretary to the National Secular Society, and in 1869 was appointed special lecturer to that body.

For many years Mr. Watts was Secretary to the National Secular Society, and in 1869 was appointed special lecturer to that body. Its official reply to the Christian Evidence Society was from his pen, and was considered a temperate and effective piece of work.

In 1874 Mr. Watts acquired the printing and publishing business previously carried on by Austin Holyoake at 17, Johnson’s Court, that Freethought centre from which of late years have radiated so many intellectual activities. He purchased the Secular Review from Mr. G. J. Holyoake in 1877, and opened premises in Fleet Street for its publication under his own editorship, and for the sale of Freethought literature. A year later Mr. Watts joined with others of kindred views in establishing the British Secular Union, of which the then Marquis of Queensberry became President, Professor Pasteur and Ernest Renan Vice-Presidents, and Victor Hugo one of the honorary members.

He purchased the Secular Review from Mr. G. J. Holyoake in 1877, and opened premises in Fleet Street for its publication… A year later Mr. Watts joined with others of kindred views in establishing the British Secular Union, of which the then Marquis of Queensberry became President, Professor Pasteur and Ernest Renan Vice-Presidents, and Victor Hugo one of the honorary members.

Mr. Watts was invited to become a Parliamentary candidate for Hull in 1879. It was expected that one of the members would retire; but as this event did not occur Mr. Watts, rather than risk a division in the Liberal ranks, withdrew from the fray, after successfully addressing several meetings of the electors. It is worth noting that his political programme comprised a scheme of compulsory national education, extension of the county franchise, separation of Church and State, revision of the pension list, reform of the land laws, redistribution of seats, and an intelligent and discriminating support of the foreign policy of Mr. Gladstone. During the ensuing general election Mr. Watts worked hard on behalf of Liberalism, winning from Mr. Childers the tribute that he had never heard a more logical and eloquent speaker. Mr. Watts was also invited to contest one of the seats at Preston, but this invitation he was compelled to decline.

For most of the foregoing facts we are indebted to a little pamphlet by “Saladin,” entitled A Sketch of the Life and Character of Charles Watts, which bears no date, but appears to have been published about 1885.

Since the early eighties Mr. Watts has devoted himself mainly to lecturing, debating, and the writing of articles for Freethought periodicals. In each department he achieved a conspicuous and gratifying success.

Since the early eighties Mr. Watts has devoted himself mainly to lecturing, debating, and the writing of articles for Freethought periodicals. In each department he achieved a conspicuous and gratifying success. Many of his hearers have expressed the conviction that he was the best debater of his day. For lucid presentation of his own case and dialectical skill in exposing the weak points of his opponents he probably had no superior. And this argumentative keenness was invariably allied to a large-minded tolerance and gentlemanly courtesy. Of the numerous opponents with whom he discussed questions of theology none seems to have come away with any bitterness in his soul towards Charles Watts. His honesty of purpose and moderation of tone were from the first recognised by such skilled disputants as Dr. A. J. Harrison, the Rev. Brewin Grant, Mr. B. H. Cowper, Dr. Sexton, the Rev. A. J. Waldron, and others. The last-named clergyman showed his kindly interest in an old opponent by frequently inquiring after the health of Mr. Watts, and on one occasion travelled some distance to personally tender his sympathy and appreciation.

Charles Watts was the first British lecturer to deliver Freethought addresses in America. He paid nearly a dozen visits to that country, and his efforts received high appreciation in Canada (where he founded Secular Thought, a journal still published), as well as in the States.

Charles Watts was the first British lecturer to deliver Freethought addresses in America. He paid nearly a dozen visits to that country, and his efforts received high appreciation in Canada (where he founded Secular Thought, a journal still published), as well as in the States. A personal friend of Ingersoll, he had the greatest admiration for that brilliant orator; and in the opinion of many friends there was a striking similarity between the methods of the two men, though Mr. Watts was by temperament more methodical and self-restrained than his passionate and poetic colleague. Yet, with all Mr. Watts’s intellectual calm, he resembled Ingersoll in his power of effectively appealing to the emotions of his audience.

Avoiding alike mysticism and shallow denial, he was a true Agnostic, anxious not merely to beat down error, but to build up truth. He held that in this life there is still so much to be done for the betterment of the race that human energy should be employed in secular relations without being directed to a future life that is no more than a possibility.

Mr. Watts’s literary productions naturally consist for the most part of his lectures, and if these were all collected their number would make a formidable array upon the bookshelf. It has been said that for many years he delivered on an average between 150 and 200 lectures per annum. This means an output of intellectual force which is not adequately represented by his published works. Of these the most ambitious is a History of Freethought, published more than a quarter of a century ago. Among recent publications the collection of essays issued under the title of The Meaning of Rationalism is marked by sobriety of thought and clearness of statement, especially in its account of the principles on which all forward theological movement is based. Mr. Watts was never a defiant Atheist of that type which some Christian Evidence writers treat as the sole form of Freethought. He firmly maintained the necessary limitations of human knowledge, but never claimed to determine finally the scope of human capacity. Avoiding alike mysticism and shallow denial, he was a true Agnostic, anxious not merely to beat down error, but to build up truth. He held that in this life there is still so much to be done for the betterment of the race that human energy should be employed in secular relations without being directed to a future life that is no more than a possibility.

Genial, just, and kindly, his capacity for friendship and his warm domestic sympathies afforded a worthy background to his public activities.

As a man, no less than as a writer, was Charles Watts deserving of admiration and esteem. Genial, just, and kindly, his capacity for friendship and his warm domestic sympathies afforded a worthy background to his public activities. The tempered wisdom which we term common sense was eminently characteristic of him; and he exhibited some of the finest elements of the religious spirit, even though in hot rebellion against its dogmatic formulas.

Mr. Watts was twice married, his surviving wife being the daughter of a well-known Nottingham Freethinker. He leaves two sons and three daughters to mourn his loss. His eldest son was the founder of the Rationalist Press Association and of the Literary Guide, which he has edited from its commencement.

Charles Watts was one of those whose memory deserves to be kept green, and the world, not merely of Freethought, but of all thought, is the poorer by his loss.

The pioneers of British Freethought had to struggle against conditions much more seriously adverse than those which exist to-day. It is for us who profit by their labours to see that their work does not die with them. Charles Watts was one of those whose memory deserves to be kept green, and the world, not merely of Freethought, but of all thought, is the poorer by his loss.

CHARLES T. GORHAM

The body of Mr. Watts was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on the Wednesday following his death. At the service in the chapel there were present a large number of relatives and friends, including Mr. and Mrs. Charles A. Watts, Mr. and Mrs. C. H. Cattell, Mr. and Mrs. W. J. Davidson, Mr. and Mrs. Von der Heyde, Miss Sallie Watts, Miss Gladys Watts, Miss Jessie Nowlan (sister-in-law), Mr. Frederick Chater, Mr. F. Cattell, Mr. C. Cattell, Miss Fanny Cattell, Mr. F. J. Gould, Mr. Arthur B. Moss, Mr. W. Heaford, Mr. John Watts, Mr. Joseph McCabe, Mr. H. L. Braekstad, Mr. N. Lidstone, Mr. Griffith Humphreys, Mr. Charles E. Hooper, Mrs. Herbert Gilham and Mrs. E. Bayston (two of Mr. Watts’s oldest and dearest friends), Mr. Wilber (representing the Leicester Secular Society), Mr. Henry Taylor and Mr. James Pollitt (representing the Failsworth Secular Sunday School), Mr. H. Buxton (representing the Liverpool Ethical Society), Mr. A. G. Whyte, Mrs. Charles T. Gorham, Mrs. T. E. Green, Mr. W. R. Seelie, Mr. T. Ganter, Mr. W. J. Ramsey, Mr. W. E. Marsch (representing the employees of Messrs. Watts & Co.), Mr. F. Hovenden, Mr. Henry Nordblom, Mr. W. C. Freeman, Mr. Herbert Burrows, Mr. Arthur A. Kohn, Mr. C. G. Gumpel, Madame Buatier, Mrs. I. B. Crowe, Mr. J. T. Lloyd, Mr. Alfred Marsh, Mr. A. Sumner, Dr. Charles Read, the Rev. A. J. Waldron, Miss J. Ellwood, Mr. E. Cross, Mr. and Mrs. Child, and many others. Mrs. Charles Watts was too unwell to be present.

The form of service was similar to that used at Mr. Holyoake’s funeral. There were many beautiful wreaths, the senders (apart from members of Mr. Watts’s family) being Dr. and Mrs. Stanton Coit, Mrs. H. Bradlaugh Bonner, Mr. and Mrs. Holyoake Marsh, Mrs. Herbert Gilham, Mrs. E. Bayston, Mr. and Mrs. Charles T. Gorham, the Rationalist Press Association, Mr. Frank Moore, Mr. and Mrs. Reginald Cann, Mr. J. Munday, the employees of Messrs. Watts & Co., Mr. and Mrs. W. E. Marsch, and Mr. and Mrs. A. Sumner.

Mr. F. J. Gould officiated at the service. His address and that of Mr. Arthur B. Moss, who followed, will be published in these columns next month.

The remains were interred the next day at Highgate Cemetery, in a grave next to that where the ashes of George Jacob Holyoake rest. Dr. Charles Read, a much-revered friend of Mr. Watts, read an impressive address, which we hope to reproduce in our next issue.

Resolutions of sympathy with Mr. Watts’s family, and expressing high appreciation of the deceased’s services on behalf of Rationalism, have been received from the Leicester Secular Society, the Wood Green Ethical Society, the Hyde Labour Church, and the Liverpool Ethical Society. At the Leicester Secular Hall Mr. J. R. Macdonald, M.P., and Mr. Sydney Gimson both paid a generous tribute to Mr. Watts’s devotion to the various humanitarian movements with which he was connected.

The many friends—considerably more than a hundred—who have sent sympathetic letters to Mrs. Charles Watts and Mr. Charles A. Watts are asked to accept this acknowledgment. Mr. W. Stewart Ross (Saladin) contributes to the Agnostic Journal of February 24th a lengthy “At Random” in warm appreciation of his old-time colleague, Mr. Charles Watts. A copy of the issue will be sent free to any reader of the Literary Guide on receipt of five halfpenny stamps.

From: The Literary Guide, No. 118, 1 April 1906

(At the Crematorium, Golders Green, February 21st, 1906.)

We men, who in our morn of youth defied

William Wordsworth, ‘Sonnets from The River Duddon: After-Thought’

The elements, must vanish—be it so!

Enough, if something from our hands have power

To live, and act, and serve the future hour.

The doors of this solemn building opened but a few weeks ago to admit the remains of a master in the sphere of modern thought. To-day they open again to admit one who, on the front of his latest and ripest hook of essays, placed the modest dedication: “To George Jacob Holyoake, my Guide, Philosopher, and Friend.” As we observe how closely the dates of their passing approached, we naturally recall the song of David over the bodies of two heroes of Israel; “They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in death they were not divided.”

If we use the conmonplace tongue of the newspaper, we shall say that Charles Watts died on February 16th, 1906. A more exact language would say that on that day he joined—

The choir invisible

George Eliot, ‘The Choir Invisible’

Of those immortal dead who live again

In minds made better by their presence.

He belonged to Humanity, took part with distinction in the march of the Progressives, touched the emotions and kindled the thoughts…

So, likewise, we may take two views, one limited, the other broad, of his function in the world. A husband, a father, has gone; and there is sorrow in the hearts of a wife, of daughters, of sons; and a hush has stolen softly into a household that was familiar with his cheerful personality, his genial companionship, his hearty salutations. But he was a member of a wider society. He belonged to Humanity, took part with distinction in the march of the Progressives, touched the emotions and kindled the thoughts of myriads of men and women in the Old World and the New, and now, in silent dignity, awaits the announcement from us—“Well done, good and faithful servant.”

Heresy—which is the vision of fresh truth—had set a manly chord vibrating in his soul while he was yet a lad at Bristol. He was nerved by the voice and example of Mr. Holyoake to tread the rough and splendid road of Freethought.

The service to the Secular ideal which Charles Watts so actively rendered was not only good and faithful; it extended through a long period. For more than forty years he was an energetic propagandist of the philosophy that is surely displacing every form of Theism. Heresy—which is the vision of fresh truth—had set a manly chord vibrating in his soul while he was yet a lad at Bristol. He was nerved by the voice and example of Mr. Holyoake to tread the rough and splendid road of Freethought. Amid the roar and business of London he worked for a livelihood, he made friends, he practised with zest the dramatic art which afterwards lent a charm to his platform delivery. And, all the time, thought and feeling were developing, maturing, energising, until the prophetic impulse must needs issue in public action. He became known as an advocate, in speech and print, of Secularism.

In the latter years of his career one could readily notice that, whenever he lectured in assembly halls which he had visited on many previous occasions, grey-headed men and women were wont to attend who had taken a liking to him when he and they were young, and had remained attached both to his person and his teachings.

The captains of the movement—Bradlaugh, Holyoake, Watts, and others—had each their fine qualities and worthy methods. No profit can come of comparing these qualities and methods minutely. Let each be praised. There was in Charles Watts’s character a strain of benignity which gave a serene and liberal manner to his writing, and imparted a marked courtesy to his style on the platform. His frank and open face, and a certain grace of attitude and gesture, easily put him on good terms with his audiences. The many, the innumerable, discussions in which he engaged were singularly free from clements of bitterness and recrimination, so far as his own share in them was concerned. And when, as was his custom, he referred to an opponent in debate as “My friend,” the words were not used in mere etiquette, but were uttered in a tone that implied a real respect. In the latter years of his career one could readily notice that, whenever he lectured in assembly halls which he had visited on many previous occasions, grey-headed men and women were wont to attend who had taken a liking to him when he and they were young, and had remained attached both to his person and his teachings.

A time will come when they who write the true history of England—that is, its moral, intellectual, and social history—will give honour to the self-sacrifice involved in the public labours of such pioneers as Charles Watts.

A time will come when they who write the true history of England—that is, its moral, intellectual, and social history—will give honour to the self-sacrifice involved in the public labours of such pioneers as Charles Watts. Even those of us who have known Secularism from within have inadequately measured the wear, the tear, the nervous and muscular strain associated with constant travels by road, by rail, by boat; in day and night ; in all weathers, fair or tempestuous; subject to divers accidents by the way and inconveniences of accommodation. We too thoughtlessly assumed these experiences to be the natural lot of the lecturer, and were far too slow to detect the genuine heroic spirit that carried the man through infinite hardships in the name of the Right. Did Charles Watts falter amid such difficulties, or before the yet severer test of social reproach against his so-called unbelief? He did not falter. His seventieth year found him still striving for the abolition of theology and the establishment of a nobler doctrine of life. In 1864 he was strenuously assisting the objects of the National Reformer. In 1905 he was still pursuing the task of rationalising the public ideas by means of the pen and platform. The secret of this devotion he has himself disclosed in what is perhaps the finest passage he ever wrote. Having, in one of his essays, referred to such qualities as Magnanimity and Justice, he proceeds to say :—

To these great virtues of the mind we must add, as essential to true happiness, what are called the virtues of the heart, such as the fervour of Enthusiasm, and the finer fervour of Sympathy, or, to use the better name, Love. For, if wisdom gives the requisite light, love alone can give the requisite heat. Wisdom, climbing the arduous mountain solitudes, must often let the lamp slip from her benumbed fingers; must often be near perishing in fatal lethargy amid ice and snowdrifts if Love be not there to cheer and revive her with the glow and the flames of the heart’s quenchless fires.

Charles Watts, The Meaning of Rationalism (1905)

It was this sentiment of benevolence that gave Charles Watts the courage to fight for reform in religion, in politics, in the social field, in education. Humanity gave him a commission to work on her behalf, and, in the light of the funeral fire, the commission is here laid down as honourably fulfilled.

A multitude of minds are to-day, on the other side of the Atlantic, thinking more sanely, and a multitude of hearts are beating more humanely, because they responded to the words of Charles Watts.

We acknowledge its fulfilment. We thank him for ourselves and for our children. The thanks given in this hour and place are offered in the name of the tens of thousands who were moved by his appeal in Britain, in Canada, in the United States of America. Like Wesley, he took the world for his parish. One continent did not suffice for his zeal. A multitude of minds are to-day, on the other side of the Atlantic, thinking more sanely, and a multitude of hearts are beating more humanely, because they responded to the words of Charles Watts. Ingersoll took him by the hand, and recognised in him a valiant co-helper.

He rejoiced at the spread of Rationalist literature among the millions in town and village. He was proud to recollect his own earnest share in the enterprise of light.

He saw many happy fruits of his labour. Many were the personal testimonies which flocked upon him in his closing days—signs of gratitude and affection, like flowers heaped at his threshold. He knew the Churches were softening down the harsher features of their creeds. He knew old bigotries were dying. He knew the larger thought was penetrating the very cathedral. He rejoiced at the spread of Rationalist literature among the millions in town and village. He was proud to recollect his own earnest share in the enterprise of light.

It is customary, and perfectly right, in a limited sense, to say of such a man’s death that it has left us poorer. But, rising to the social standpoint, we feel that the Past itself—the Past which inspires us and so profoundly governs us—has become richer by the incorporation of his memory.

It is customary, and perfectly right, in a limited sense, to say of such a man’s death that it has left us poorer. But, rising to the social standpoint, we feel that the Past itself—the Past which inspires us and so profoundly governs us—has become richer by the incorporation of his memory. He is now ranked with the cloud of witnesses that encompass the struggle and progress of the living. He is definitely and irrevocably numbered with the throng of influences that aid in shaping the destinies of the race. For we that yet live possess in the records of the action and speech of the dead an ample treasure of encouragement and good counsel. We are glad to have known our dear friend; glad to have looked upon his face, to have pressed his hand, and hearkened to his voice. We salute his achievements and his career.

Memories, all too bright for tears,

W. Gaskell, Hymn 126 in the Service of Man

Crowd around us from the past;

Faithful toiled he to the last,

Faithful through unflagging years.

All that makes for human good,

Freedom, righteousness, and truth,

Objects of aspiring youth

Firm to age he still pursued.

(At the Crematorium, Golders Green, February 21st, 1906.)

And what was the philosophy that Charles Watts taught? It was the value of this life—the only life we really know of—and the importance of doing the best we can to promote the well-being of our fellows, apart altogether from the consideration of any life in the future.

A few weeks ago we stood in this building by the coffin of the venerable George Jacob Holyoake; now, within a little month, we stand by the remains of his chief apostle and colleague in the cause of intellectual freedom—our dear departed friend, Charles Watts. Of him we can assuredly say that he was a warrior who fought with great earnestness and enthusiasm in the army of Freethought for a period close upon half a century. Up to the last his earnestness and ardour in the cause of truth were unabated. It is a significant fact that Charles Watts, like most of the foremost leaders in the Rationalist movement, was born of Christian parents; yet he became one of the most popular advocates of the Secular philosophy that we have ever known. In this country, as in America, he did splendid work. By his impassioned eloquence and his great argumentative skill he caused thousands to think and reason concerning their religion who otherwise would have remained undisturbed in their ignorance, and he led them by the clear light of reason to repudiate error and superstition wherever they found them, and to take their place on the side of science and progress.

It is a significant fact that Charles Watts, like most of the foremost leaders in the Rationalist movement, was born of Christian parents; yet he became one of the most popular advocates of the Secular philosophy that we have ever known.

I speak with a long experience of the valuable work accomplished by our deceased friend. I first met Mr. Watts nearly thirty years ago. I was just entering the Freethought movement, and he gave me a friendly hand and an encouraging word, and many a time since he has cheered me in my work. Mr. Watts was a model advocate. He always appealed to reason; but, by his attractive style of address, he captivated the emotions as well as the intellect. Indeed, in the gentle art of persuasion he had few equals. Not only was he a splendid advocate; he was also a great debater. Always courteous and dignified in his method, he strove to avoid giving offence, so that his opponent, though differing widely from: him in opinion, could not help admiring and respecting him as a man. And what was the philosophy that Charles Watts taught? It was the value of this life—the only life we really know of—and the importance of doing the best we can to promote the well-being of our fellows, apart altogether from the consideration of any life in the future.

“Man’s duty from a Secular standpoint,” he said, “is to learn the facts of existence; to acquire the power of doing right; to progress in virtue and intelligence; to seek to promote the intelligence of others; in a word, to endeavour to remove from society the present inequalities, and to secure the greatest happiness of the greatest number.”

“Man’s duty from a Secular standpoint,” he said, “is to learn the facts of existence; to acquire the power of doing right; to progress in virtue and intelligence; to seek to promote the intelligence of others; in a word, to endeavour to remove from society the present inequalities, and to secure the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” Mr. Watts knew, however, that it was an impossibility to do this without first pulling up the weeds of error before he planted the seeds of truth. But in destroying error he was always careful to scatter in profusion the seeds of doubt, of investigation, of truth. Indeed, Mr. Watts possessed more of a constructive than a destructive mind. He could expound the principles of a new philosophy with as much skill as he could expose the errors of an old one. And Secularism, or all that is implied in the term Rationalism, was to him a religion (though he preferred the word “philosophy”)—a religion whose practical value could be tested here and now. He agreed with Thomas Paine that religion does not consist in our beliefs or disbeliefs, but in “doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make our fellow creatures happy.” And that is what he strove to promote during the whole of his career. He took great interest in political and social reforms; but, for his part, he considered that reforms in religion were most important. Several times he visited America, and stirred up the enthusiasm of the people in favour of intellectual freedom; and he was always cheered in his work by that incomparable worker for human emancipation—the illustrious Colonel Ingersoll.

Secularism, or all that is implied in the term Rationalism, was to him a religion (though he preferred the word “philosophy”)—a religion whose practical value could be tested here and now.

Mr. Watts has finished his work; he rests from his labour. He has played his part on the great stage of life, and he has played it well. He may not have a monument erected to his memory, but he has won a place in the affections of all who have had the pleasure and privilege of coming within the sphere of his influence.

Farewell, dear friend. We pay you the homage of our admiration and our tears.

(At Highgate Cemetery, February 22nd, 1906.)

We are met here to-day to render our last tribute of respect to the earthly remains of Charles Watts; but our regard and affection for his memory will never cease as long as our consciousness shall last.

We are met here to-day to render our last tribute of respect to the earthly remains of Charles Watts; but our regard and affection for his memory will never cease as long as our consciousness shall last.

In laying the ashes of Charles Watts, my friend and your very near and dear relative, side by side with those of his lifelong friend, George Jacob Holyoake, I should like to add a few words of kindly appreciation to those which were spoken at the Cremation Service yesterday.

If, in carrying out his mission, he had to fight against bigotry, superstition, and ancient prejudices, he fought honourably, graciously, and without bitterness of spirit, so that even his opponents bore testimony to his fairness and courtesy in debate.

In his private life Mr. Watts was a devoted husband, an affectionate father, and a faithful friend; and he will always be tenderly and gratefully remembered by those whom he loved so much, and by whom he was so much beloved. In his public life he was highly esteemed as a missionary of the Gospel of Reason; and if, in carrying out his mission, he had to fight against bigotry, superstition, and ancient prejudices, he fought honourably, graciously, and without bitterness of spirit, so that even his opponents bore testimony to his fairness and courtesy in debate. His motto was that of the noble-souled Marcus Aurelius: “I seek after Truth, by which no man was ever yet injured”; and, following the injunction of the Apostle Paul, he sought to “prove all things,” and to hold fast to that which he found to be good.

Rationalism regards religion as a personal matter, and urges that it consists not in believing certain creeds and dogmas, but in doing good, adhering to truth, fostering love, and in enhancing the happiness of others as well as ourselves.

From my point of view, as a liberal and enlightened Christian of the most modern type, I claim my friend Charles Watts as a truly religious man, although he would not have called himself such, through fear of being misunderstood. In his last work, The Meaning of Rationalism, the proof sheets of which saw him revising when he was staying last summer at Hampstead to be under my care, he speaks as follows: “Rationalism regards religion as a personal matter, and urges that it consists not in believing certain creeds and dogmas, but in doing good, adhering to truth, fostering love, and in enhancing the happiness of others as well as ourselves.” On this I remark: No better definition than this can be given of true religion; for the very spirit and essence of the Christian faith, interpreted in the light of modern knowledge, consists in being good and doing good without hope of reward or fear of punishment. This is the life that Charles Watts lived; therefore, from his own point of view as well as from mine, I may call him a truly religious man.

And now we pay to the mortal remains of Charles Watts our last tribute of reverent respect, and commit the ashes to their final resting place. His memory will ever remain fresh and fragrant in the hearts and minds of his near and dear ones, and also in those of his many friends in England and America who held him in such high regard.

And now he has passed from our midst, and has entered into the Great Unknown, beyond this sense-life of ours. Of any life beyond the present he had no expectation; but as, from his philosophical position, he could neither affirm nor deny its possibility, he was prepared either for the eternal sleep or for the larger and nobler life beyond this earth-life, if such there might be. Like his friend, George Jacob Holyoake, who has only so recently passed away, he would have hailed with joy and gladness the thought of a life beyond the grave, full of the noblest satisfactions of which our nature is capable, if he could have found sufficient evidence in its favour to enable him to do so. It was only against the ignoble and unworthy presentations of that life, and the terms of admission thereto according to the orthodox Christian belief, that he protested. Most truly does the late Frederic W. H. Myers say in one of his essays: “If the belief in a life to come should ever retain as firm possession of men’s mind as of old, that belief will surely be held in a nobler fashion. That life will be conceived not as a devotional exercise, nor as a passive felicity, but as the prolongation of all generous energies and the unison of all high desires. It may be that, till we can thus apprehend it, its glory must be hid from our eyes. Only perhaps when men have learnt that virtue is its own reward may they safely learn also that that reward is eternal.”

And now we pay to the mortal remains of Charles Watts our last tribute of reverent respect, and commit the ashes to their final resting place. His memory will ever remain fresh and fragrant in the hearts and minds of his near and dear ones, and also in those of his many friends in England and America who held him in such high regard. Farewell!

I had the pleasure of knowing the late Mr. Charles Watts as an opponent and a friend. Some of the most thrilling and interesting experiences of my public life were when engaged in debate with the late Rationalist champion.

I had the pleasure of knowing the late Mr. Charles Watts as an opponent and a friend. Some of the most thrilling and interesting experiences of my public life were when engaged in debate with the late Rationalist champion. As an orator he took his place easily in the first rank, and as a debater he was second to none. We have met in discussion among the hard-headed thinkers of the North, among the artisans of the Midlands, and also before the cosmopolitan crowds of London. Mr. Watts was never vulgar, always fair, accepted men as he found them, and believed intensely in human nature. His optimism was rarely shaken, and even when he came across a downright scamp he always had a kindly word of excuse for such degeneration. His interest in the social well-being of the people was no platform trick, but you felt it glowing from his whole personality. I was proud of his friendship, and felt it an honour to be allowed to visit him in his last illness. He died as he lived—a Secularist and a man. Personally, the readers of the Literary Guide will forgive me when I say that I hope to meet him again.

Mr. Watts was never vulgar, always fair, accepted men as he found them, and believed intensely in human nature.

Before a crowded audience at the South London Ethical Society, on Sunday, February 24th, Mr. H. Snell preceded his lecture with a few words upon the death of Mr. Charles Watts, after which, the audience meanwhile standing, the “Dead March in Saul” was played.

The voices of men and women like Carlile, Hetherington, Watson, Owen, Emma Martin, Harriet Law, Wheeler, Bradlaugh, and now Holyoake and Charles Watts, call to us from the grave to be worthy of the legacy of freedom they helped to win for us. The cause they represented was the cause of truth, freedom to speak the truth, and also devotion to the duties of the world we know.

In the course of his remarks Mr. Snell said:—

One by one the old landmarks are worn away, and one by one the old warriors of Freethought seek their rest. Only a week or two ago the most venerable of its leaders passed away in the person of Mr. George Jacob Holyoake, and now to-night we mourn the loss of Mr. Charles Watts. Our late friend was a member of this Society, and he was deeply interested in its work. He had lived a long and useful life, his great natural talent for public speaking and debate being placed unreservedly at the service of the Freethought movement. In that stern cause I had the privilege of being his colleague for something like twenty-three years.

Mr. Watts was one of a small band of intrepid pioneers who broke down with strong hands the barriers to free thought and free speech. They made possible this movement we represent here to-night. Without them it would not and could not have existed.

Mr. Watts was one of a small band of intrepid pioneers who broke down with strong hands the barriers to free thought and free speech. They made possible this movement we represent here to-night. Without them it would not and could not have existed. The Ethical movement has never learned to pay its debt of acknowledgment to them; but I do so here to-night in your name. The voices of men and women like Carlile, Hetherington, Watson, Owen, Emma Martin, Harriet Law, Wheeler, Bradlaugh, and now Holyoake and Charles Watts, call to us from the grave to be worthy of the legacy of freedom they helped to win for us. The cause they represented was the cause of truth, freedom to speak the truth, and also devotion to the duties of the world we know. Our best tribute to the dead would be a renewed determination on our part to serve more strenuously the cause to which their lives were given.

At the last meeting of the Board of Directors of the Rationalist Press Association (Mr. Edward Clodd in the chair) it was moved by Mr. Munday, seconded by Mr. Dryden, and carried: “That the Directors of the R.P.A. desire to record their sense of the great loss that they and the Association have sustained through the death of Mr. Charles Watts, and their high appreciation of his character and the life-services which he has rendered to the cause of truth and freedom. Further, that a copy of this resolution, with an expression of their deep sympathy with Mrs. Watts and family, be forwarded to Mrs. Watts.”

A similar resolution has been passed by several other Rationalist and Ethical organisations.

Many human beings are sensible and friendly and kind; able to combine together to carry out wise policies. It is […]

No poet since Shelley sings more loftily or with more fiery passion or with finer thought than Swinburne when he […]

I felt flattered by the remark of a hostile journalist that I was “a compendium of the cranks,” by which […]

…the only universal truths which exist are the fundamental laws of the mind. Philosophy, then, which is the science of […]