I count religion but a childish toy,

Christopher Marlowe, The Jew of Malta, prologue

And hold there is no sin but ignorance.

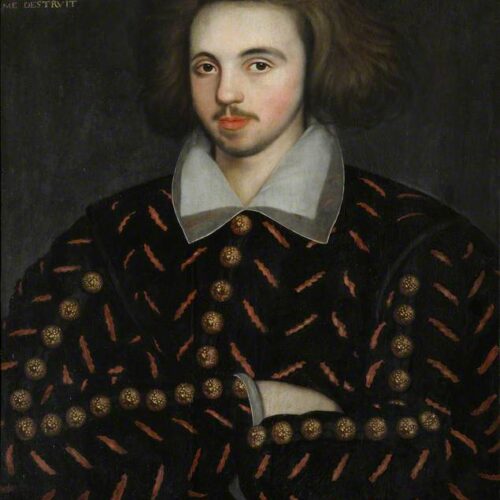

Christopher Marlowe is remembered as a dramatist of extraordinary innovation, whose work foregrounded human ambition, reason, and identity at a time when orthodoxy ruled both stage and state. A contemporary of Shakespeare, and in many ways his precursor, Marlowe wrote plays that boldly explored questions of belief, power, and personal freedom. His association with espionage, his apparent atheism, and his unapologetically human-centred worldview place him among the earliest figures in English letters whose life and work resonate with humanist values.

Born in Canterbury in 1564, the son of a shoemaker, Marlowe’s early life was marked by academic promise. He attended the King’s School before winning a scholarship to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he studied the liberal arts. Although the university initially withheld his Master’s degree, apparently suspicious of his extended absences and associations, it was eventually granted after the Privy Council intervened, citing services rendered to the Queen. The exact nature of those services remains uncertain, but this official protection cemented his reputation as a government agent.

In London, Marlowe quickly became the dominant voice of the new professional theatre. His first major play, Tamburlaine the Great (1587), defied medieval theatrical conventions. It cast a Scythian shepherd as a brutal but brilliant conqueror, replacing divine fate with sheer human will. The language was elevated, the form expansive, and the perspective unapologetically secular.

He followed this with Doctor Faustus (c. 1589–92), whose eponymous scholar trades his soul not for eternal life, but for 24 years of power, pleasure, and knowledge. In The Jew of Malta (c. 1589–90), Marlowe created one of the most notorious characters in early modern drama: Barabas, a Jewish merchant turned vengeful antihero. The play trades in the racial and religious prejudices of its day, portraying Jews, Muslims, and Christians alike through a lens of corruption, violence, and deceit. Its antisemitic caricature of Barabas, and the gleeful brutality of its portrayal of Turks and friars, are inseparable from the period’s dominant ideologies and cannot be redeemed by irony alone. But they do function as part of a broader satire in which all religions are implicated, and moral hypocrisy, rather than doctrinal error, is the target.

The play’s influence is unmistakable. Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596), written a few years later, borrows its structure and central conflict — a Jewish figure wronged by Christians, and the court that resolves the dispute — but tempers the depiction with psychological realism. But Marlowe offered no such comfort. He was more interested in exposing the cruelty at the heart of European power than in offering any redemptive resolution.

His final complete play, Edward II (c. 1592), was perhaps the most daring of all. It chronicled the fall of a king undone not by war or madness, but by love — specifically, his love for another man. In an era when same-sex desire was not only unstageable but unspeakable, Marlowe made it central. The relationship between Edward and his favourite, Gaveston, is tender, sensual, and ultimately catastrophic. Their love becomes the focal point of political collapse, not because of its immorality, but because of the intolerance it provokes. Where Shakespeare’s most political plays, such as Richard II or Julius Caesar, cloak their critiques in allegory and ambiguity, Edward II confronts the audience with a king whose personal and political downfall is inseparable from his sexuality. It remains one of the most strikingly modern plays of the early modern stage.

Marlowe’s posthumous reputation has often been summarised in three words: gay, atheist, spy. Each is grounded in evidence, though none can be stated with absolute certainty.

The spy connection is the most documentable. His unexplained absences from Cambridge align with moments of political intrigue abroad, and his degree was only granted after senior intervention linked to his supposed loyalty to the Crown. He associated with known agents, and his death occurred in the company of men tied to intelligence work.

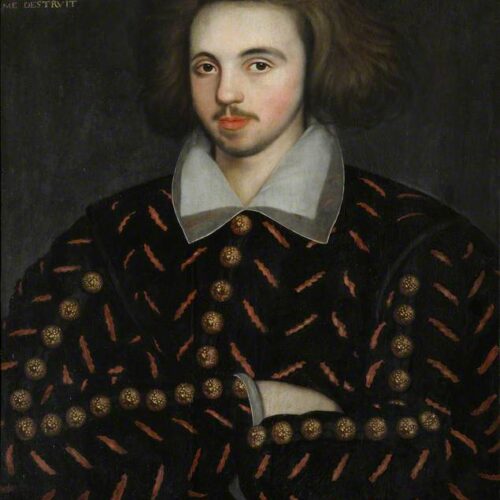

His sexuality was a subject of gossip in his lifetime and literary interest thereafter. The homoerotic opening scene in Dido, Queen of Carthage (c. 1586) is a non-sequitur in plot terms to the play that follows, existing only to show the god Jupiter passionately fondling Ganymede and showering the lad with romantic overtures; the story of Zeus’ abduction of Ganymede was already a familiar homoerotic trope to university-educated men. Edward II centres a romantic and sexual bond between two men. Informers accused him of expressing same-sex desire openly. One of the most quoted lines from the posthumous Baines note alleges that Marlowe said ‘all they that love not tobacco and boys are fools’.

The same document lists a litany of heretical statements: that Jesus was ‘a bastard and his mother dishonest’, and that ‘the first beginning of religion was only to keep men in awe’. Whether Marlowe actually said these things is impossible to know. The report was compiled during a climate of fear, shortly before his death. But the themes it describes match what can be found in his plays, which repeatedly question divine authority and portray religion as a political tool.

In Doctor Faustus, the rejection of traditional theology is explicit. Faustus scorns all forms of sanctioned knowledge, saying: ‘Philosophy is odious and obscure… Divinity is basest of the three, unpleasant, harsh, contemptible, and vile.’ His fall is framed not simply as sin but as the tragic result of human striving in a universe where answers are elusive and freedom comes at a cost.

Marlowe transformed English drama by making it about the individual: ambitious, flawed, and morally ambiguous. His characters are not guided by fate or virtue but by desire and intellect. They test the limits of what it means to be human, and suffer the consequences of that pursuit.

His work championed the power of human speech and reason. It stripped inherited narratives of divine reward and punishment, placing responsibility squarely on the individual. In that sense, Marlowe can be read as one of the first great literary humanists in English. He was not a moralist but a dramatist of questions — political, sexual, spiritual — that still feel urgent.

He also opened space for voices and identities otherwise erased from public life. Edward II is perhaps the earliest English play to take same-sex love seriously as both private emotion and public crisis. Marlowe did not disguise this, and he did not flinch from its implications.

Even the strange persistence of the ‘Marlovian theory’ — the idea that Marlowe faked his death and went on to write Shakespeare’s works — is a mark of his enduring hold on the imagination. The theory is not taken seriously by scholars, but it reflects something true: that in his short life, Marlowe wrote with such force, clarity, and boldness that his shadow fell across all who followed.

Liam Whitton is Director of Communications and Development at Humanists UK, and a big fan of Marlowe and Shakespeare.

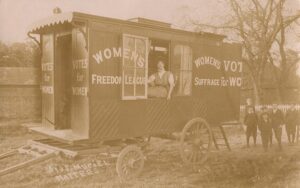

Dare to be free. Slogan of the Women’s Freedom League The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was a militant suffrage organisation, […]

I had long put on one side the purist pacifist view that one should have nothing to do with a […]

I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me. Michael Manley quoted by Rachel […]

The British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) began as the Birmingham Pregnancy Advisory Service, created to provide access to safe, legal, […]