It is necessary to the happiness of man that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving, it consists in professing to believe what one does not believe.

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason (1794)

The turn of the 18th century saw a new religious movement in Britain. Steeped in an impulse to move away from superstition, the deists emerged as a fixture of the late Stuart religious landscape. Although each deist’s beliefs could range markedly from one to the other, certain themes persisted: freethinking, a scepticism or even dislike of religious hierarchy, and the dismissal of biblical phenomena that could not be explained by reason. Although deism retained a strictly Christian focus, this Enlightenment emphasis on scientific reasoning and the questioning of established religion were significant steps towards explicitly atheist and humanist ideas, not least given the very real dangers of expressing anything deemed blasphemous at the time.

Deism also declares, that the practice of a pure, natural, and uncorrupted virtue, is the essential duty, and constitutes the highest dignity of man; that the powers of man are competent to all the great purposes of human existence; that science, virtue, and happiness, are the great objects which ought to awake the mental energies, and draw forth the moral affections of the human race. These are some of the outlines of pure Deism, which Christian superstition so dreadfully abhors…

Elihu Palmer, The Principles of Nature, or A Development of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery among the Human Species (1801)

Deism was less a set of specific beliefs and more a project to justify and rationalise Christianity, undertaken by various political and religious thinkers – some more radical than others. Sometimes called the ‘religion of nature’, deism saw the world as the creation of a god who otherwise did not intervene in human affairs.

Baron Herbert of Cherbury, sometimes referred to as ’the father of English deism’ published De Veritate (On Truth) in 1624. In this work, he emphasised the role of reason in discovering truth, and argued for a move away from religious fanaticism, persecution, and bigotry. Some have questioned whether Herbert could truly be understood as a deist, but his influence on deism was profound.

Deist figures, including Charles Blount, Peter Annet, Thomas Chubb, Thomas Morgan, and Thomas Woolston, attacked various orthodox Christian beliefs and were vehemently critical of corrupt clergymen. In his Fifth Discourse (1729) for example, Woolston labelled miraculous biblical stories, such as the raising of Lazarus from the dead, as falsehoods.

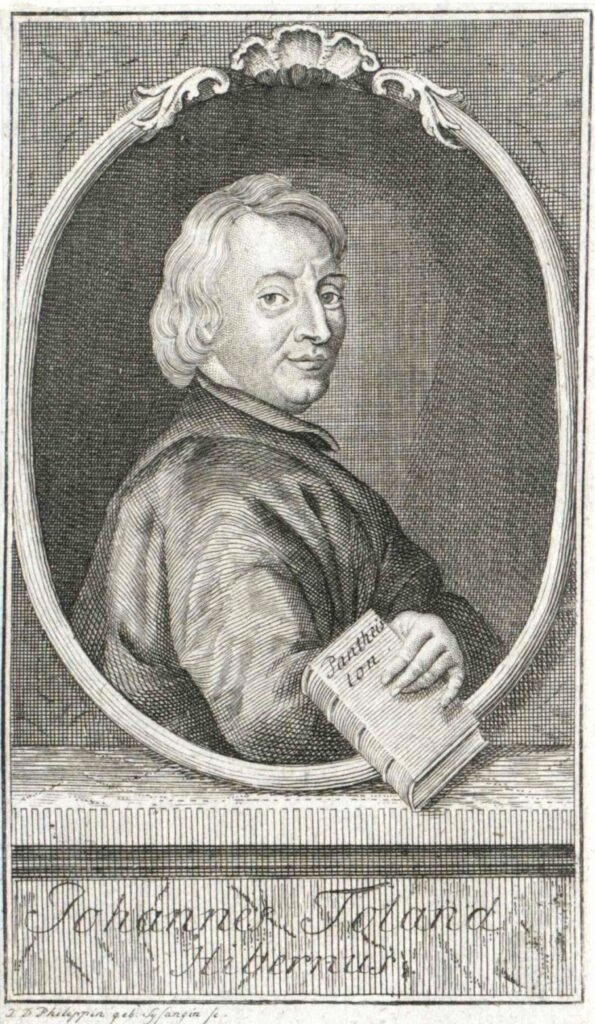

Perhaps the most controversial deist, John Toland, published his work Christianity not Mysterious in 1696. Toland stated that ‘there is nothing in the Gospels contrary to reason, nor above it’. He argued that miracles, the Trinity, and revelation were all irrelevant to human belief. The publication was so controversial that the Irish Parliament even ordered the book to be burnt by the hangman in Dublin.

As influential as the deists were, they can often be difficult to pinpoint, and debates persist over whether certain individuals could be classed as deist or not. David Hume is one such figure. He rejected revelation and argued against the belief in miracles, but he did not believe that reason was the absolute answer to religious belief.

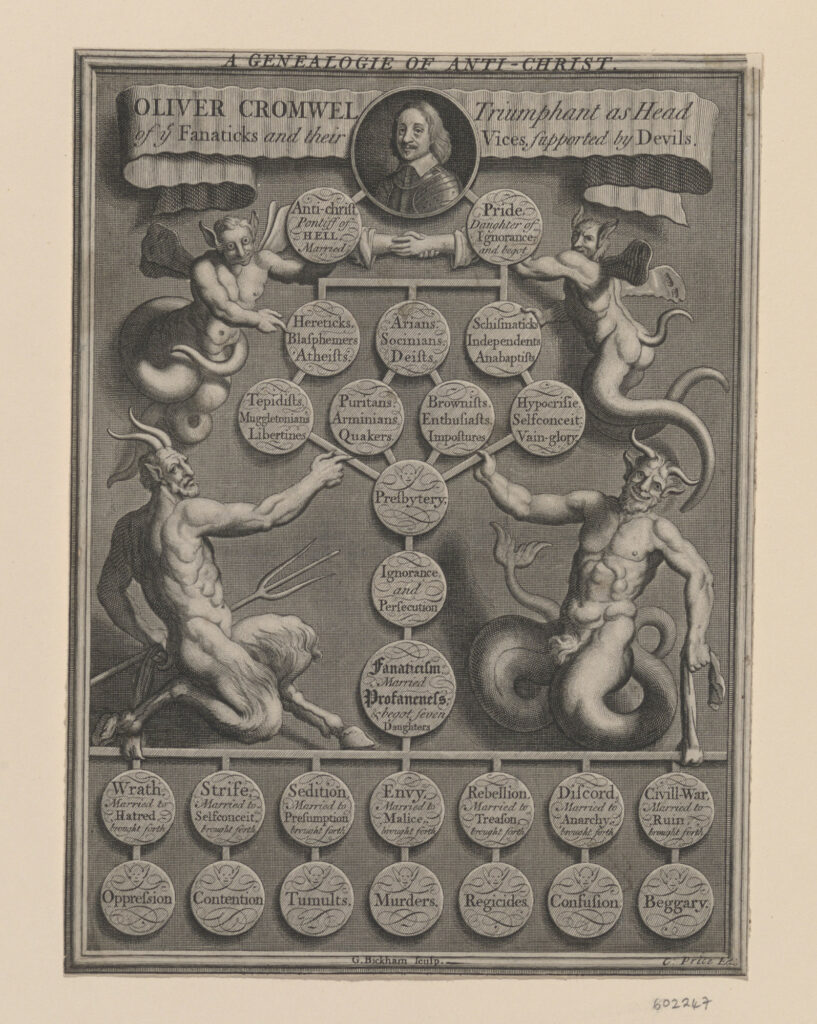

The trickiness of the ‘deist’ label is only increased by the fact that it was overwhelmingly used as a pejorative term, often to refer to someone whose religious beliefs were considered inadequate or unorthodox. A great many thinkers referred to as ‘deists’ may not have considered themselves as such. Arians and Socinians (sceptics and deniers of the Holy Trinity), religious dissenters, freethinkers, and other nonconformists were often indiscriminately referred to as ‘deists’. Some who did define themselves as deists were accused of being atheists seeking to avoid the penalties of outright unbelief. Lecturing in London in 1692, scholar and philologist Richard Bentley suggested: ‘Some Infidels… to avoid the odious name of Atheists, would shelter and skreen themselves under a new one of Deists, which is not quite so obnoxious’.

A great anxiety of the period was that England would slip back into a civil war and once again become a commonwealth. Deism was often seen as part of a slippery slope towards another great upheaval of society, hence why its proponents were heavily criticised by secular and religious authorities alike.

Deism quickly spread to France, with figures such as Voltaire, Robespierre, and Rousseau adopting the philosophical position. Deism was not only a key aspect of the ideological basis for the French Revolution, but also of what was referred to as ‘The Cult of the Supreme Being’, established briefly by Robespierre as France’s state religion. This stood in conscious opposition both to Catholicism, and to the atheist ‘Cult of Reason’: maintaining a belief in a creator god, but also prizing reason and human agency.

A thing which everybody is required to believe requires that the proof and evidence of it should be equal to all and universal.

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason (1794)

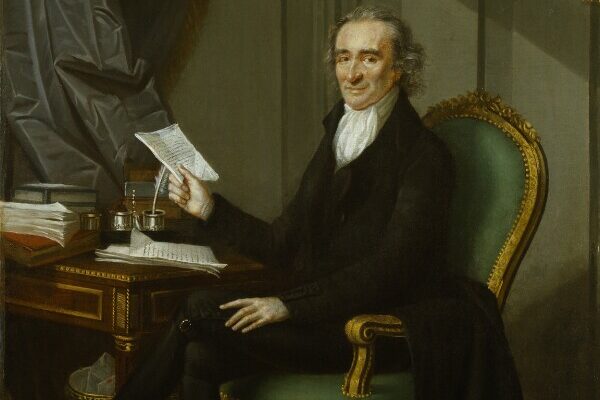

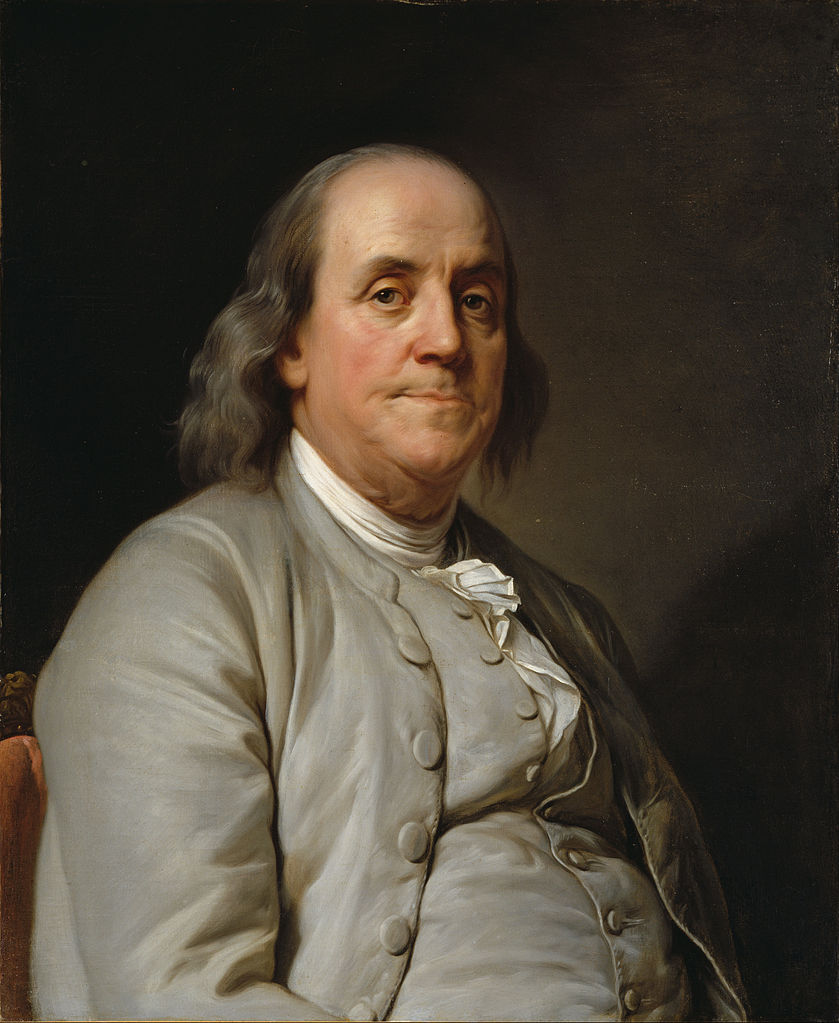

Deist ideas were also influential in America, where Thetford-born Thomas Paine became an important advocate of deism. Paine’s Common Sense, first published in 1776, had been influential in building support for the American Revolution, but it was in The Age of Reason (1794) that he made his impassioned argument for deism. In it, Paine challenged institutionalised religion and the legitimacy of the Bible. ‘A thing which everybody is required to believe,’ Paine argued, ‘requires that the proof and evidence of it should be equal to all and universal’. This, he argued, could not be said for the stories of the Bible. He went on:

Whenever we read the obscene stories, the voluptuous debauches, the cruel and tortuous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled, it would be more consistent that we called it the word of a demon, than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness, that has served to corrupt and brutalize mankind; and for my part, I sincerely detest it, as I detest everything that is cruel.

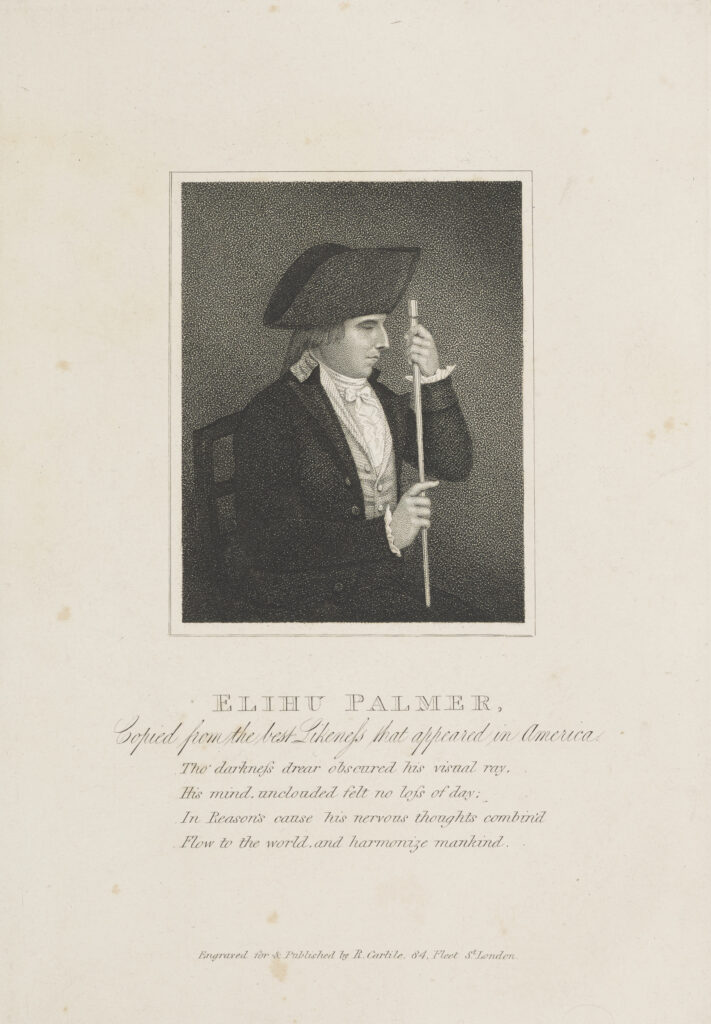

One of Paine’s greatest American adherents was Elihu Palmer, who wrote: ‘If a thousand Gods existed, or if nature existed independent of any, the moral relation between man and man would remain exactly the same.’ In this, Palmer drew a sharp distinction between theology and morality – as would the ethical societies almost a century later. Like other deists, Palmer rejected the notion of miracles, prophecy, and revelation, emphasising instead the centrality of reason, and believing in the capacity of human beings to bring about social, moral, and intellectual progress without divine intervention.

The greatest influences of deism – on the French and American Revolutions – were also significant factors in its decline in Britain. The prosecution of those publishers, like Richard Carlile, who sold works by Paine and Palmer during the first decades of the 19th century testified to the government’s fear of the violence associated with undermining religious authority. Christian revivalist movements, such as Pietism and Methodism, which emphasised a personal relationship with God, became more popular.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, when accusations of blasphemy could result in fines, imprisonment, and even in execution, those expressing deist ideas walked on dangerous ground. As J.C.A. Gaskin argued in Varieties of Unbelief:

…the ideological grip of Christian theism after the destruction of the ancient world was so complete and so tenacious that eighteenth-century deism represents, not the step toward a rationally based Christianity which it could have been, but a crucial historical step away from Christianity and toward modern unbelief.

J. C. A. Gaskin, Varieties of Unbelief (1989)

Deism occupies a muddled but important place in the history of freethought and rationalism. Although deists ultimately pivoted around the need to justify and rationalise a Christian faith, their scepticism and criticism of religious authority formed an important part of the road towards modern humanism. In their focus on what could be concluded through reason, and their emphasis on the ultimate responsibility of human beings (free from divine intervention), deists shared common ground with earlier philosophies, like those of Epicurus, and with later ones, like Felix Adler’s Ethical Culture – precursors to the modern humanist movement.

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason (1794)

Elihu Palmer, Principles of Nature (1801)

Barry Coward, The Stuart Age (1980)

J.C.A. Gaskin, Varieties of Unbelief (1989)

By Matilda Smith

Bessie Braddock was a trade union activist and politician, who devoted her life to improving the lives of others. She […]

I have been the more bold in exposing my opinion because I believe it to be the dictates of truth […]

Humanism involves not just the deletion of God from moral thought, but the development of humanity on a rational and […]

The Open University was founded in 1969 with the ambition of providing access to higher education for people who had […]