But however little it conforms or tenders allegiance, no life worth having can be isolated from the lives of others.

Laurence Housman, The Unexpected Years (1937)

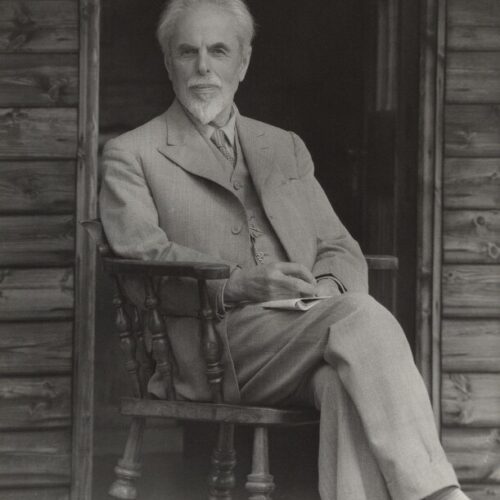

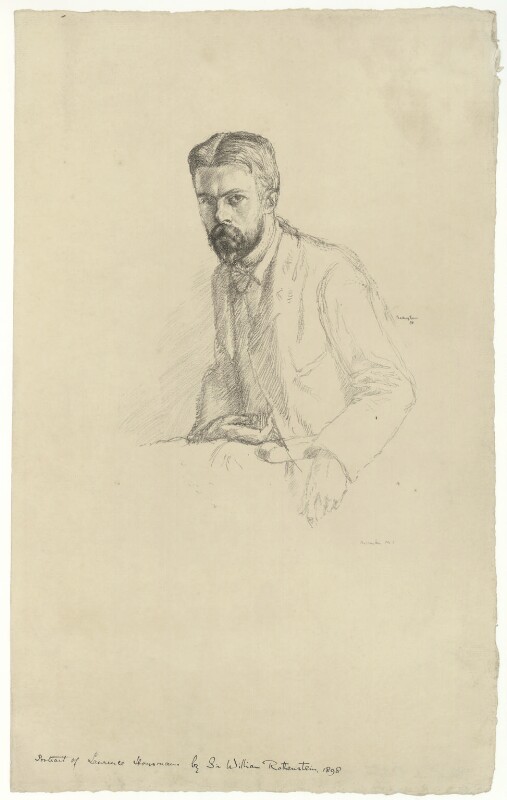

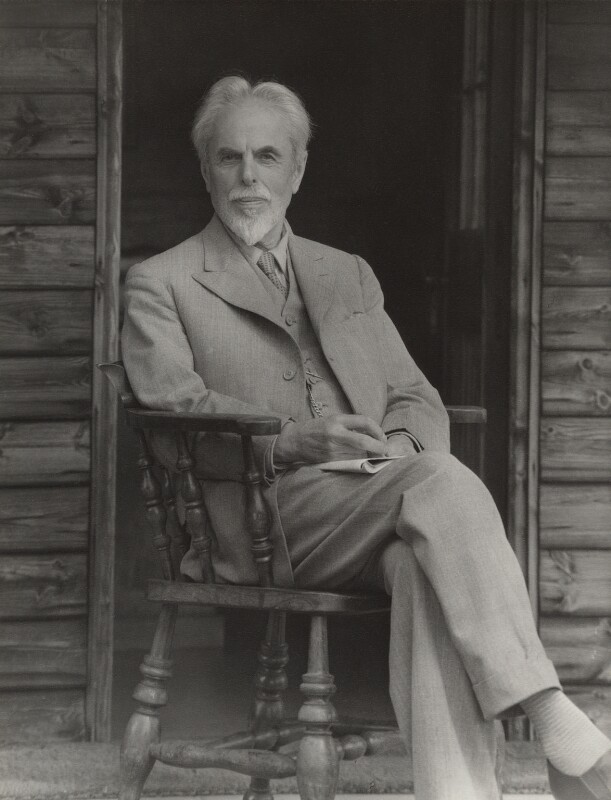

Laurence Housman was an artist, writer, and tireless supporter of women’s suffrage, as well as a Vice President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) for almost forty years. A committed socialist and pacifist, Housman was also a founding member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, the Suffrage Atelier, and the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, which sought to take a rational approach to matters of sex and sexuality. Housman’s humanism was active and lifelong, evidenced by his myriad efforts towards equality and social reform, guided by reason and compassion.

I have had pleasures and disappointments; but though the disappointments are perhaps more numerous and present to my recollection than the pleasures, I continue to find life worth having.

Laurence Housman, The Unexpected Years (1937)

Laurence Housman was the son of a politically and religiously conservative solicitor, and the younger brother of poet Alfred Edward Housman. Born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, Laurence was one of seven children, and maintained a close living and working relationship with his sister, Clemence – like him, an artist and writer – for her whole life. Following a scholarship-supported education, Laurence moved to London with Clemence in 1883, both to pursue the arts. As an illustrator, he was noted for his work on Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market, contributing also to popular periodicals like the Universal Review. Housman penned poems, essays, novels, fairytales, and plays, as well as satirical and polemic pieces.

Housman’s traditional Victorian upbringing, with its rigid sense of social propriety, contributed strongly to his becoming the activist – and humanist – he did. He viewed the household prayers of his childhood as performative and empty, and held a particular disdain for the ways in which the subject of sex was clouded in mystery, or avoided altogether. ‘It was this sanction of obscurantism’, he wrote:

… which started the breach between myself and the narrow Conservatism of my upbringing. I could not feel that any social or religious system, which so sedulously refused to tell and to face the truth, deserved respect; and though for a while I still conformed, it was without heart or conviction.

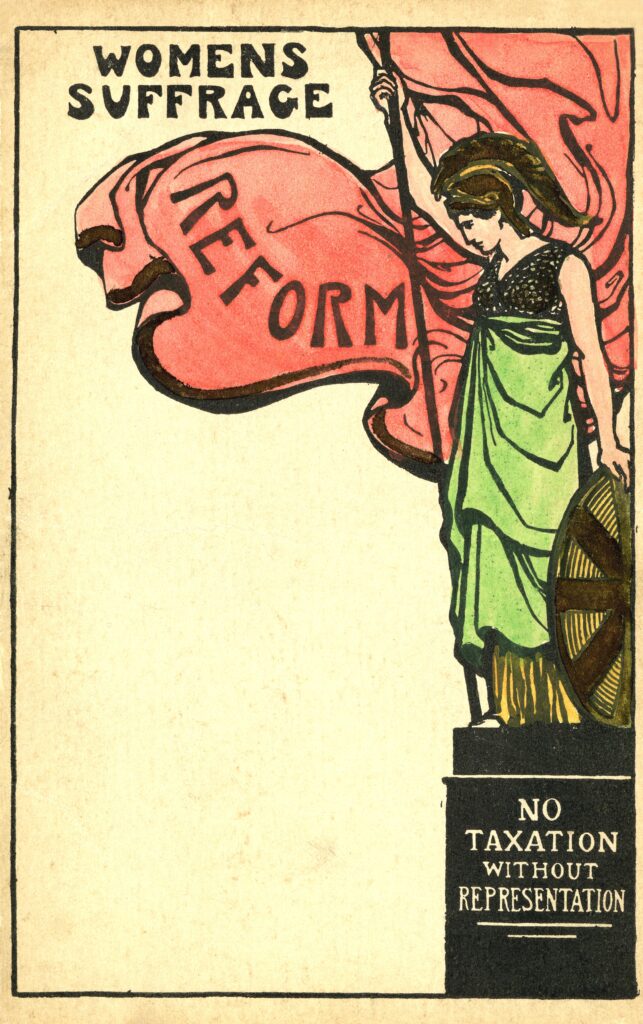

‘Taught by these monstrous perversions of modesty’, he said, ‘I had become a feminist and a suffragist long before the day of battle actually arrived.’ Both Laurence and Clemence became devoted supporters of women’s suffrage, not merely partaking in protests but helping to organise, defend, and create art for them. In 1907, Laurence was among the founding members of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage (alongside a later Ethical Union President, Henry Noel Brailsford). The Housman home became the headquarters of the Suffrage Atelier (‘An Arts and Crafts Society Working for the Enfranchisement of Women’), and Laurence wrote and spoke prolifically for the cause. In 1911, Clemence Housman became the first woman to be imprisoned for the refusal to pay taxes in the cause of suffrage. She was taken to Holloway Prison, and Laurence was the speaker at a meeting organised by the WSPU to protest her arrest. In 1914, he was a founding member of the United Suffragists.

Housman also took an active part in the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, which he co-founded with Edward Carpenter and other progressive thinkers in 1913, advocating homosexual law reform and promoting more rational attitudes to sexuality. Later renamed the British Sexological Society, E. M. Forster was also among its members, and many other humanists spoke and wrote for its causes.

Housman was a Vice President of the Ethical Union for almost four decades (1921-57): a prominent representative of the Union’s guiding principles of ‘Human Fellowship and Service’ without reference to supernatural beliefs. In 1929, he delivered the Conway Memorial Lecture in the newly opened Conway Hall on ‘The Religious Advance Towards Rationalism’.

In 1924, Laurence and Clemence Housman moved to Somerset, where they lived peacefully in Longmeadow, a house built for them. In 1952, Housman joined the Society of Friends in Street. As Clemence’s health began to fail, Laurence cared for her with the help of neighbours. She died in a Glastonbury nursing home on 6 December 1955. Laurence Housman, bereft of a lifelong companion, died on 20 February 1959.

One hears a good deal of talk nowadays about the decay of religion; and the Victorian age is spoken of as though it had been an age of faith. My own impression of it is that it combined much foolish superstition with a smug adaptation of Christianity to social convention and worldly ends.

Laurence Housman, The Unexpected Years (1937)

On his death, The Times described Housman as an ‘idealist and iconoclast… a figure of versatile and idiosyncratic distinction.’ He was appropriately characterised as a ‘born radical under a conservative skin… clothed in the formidable traditions of the Victorian era,’ which ‘he proceeded by degrees to shed’. In this way, he was typical of a generation of humanists and activists who, finding the faith and expectations of their childhoods no longer viable, embraced a practical philosophy of good works, rooted in a professed agnosticism. Housman was remembered too for:

… an ebullient humour which was very characteristic of the man, which overflowed in his intimate correspondence, and which salted a view of the world at large as something to be shocked and pin-pricked and teased into lively apprehension.

This untiring creativity, married with a powerful sense of social responsibility, underpinned Housman’s decades-long devotion to reform. He championed honesty and openness in private and public life, unafraid of defending unpopular causes, or those deemed controversial by wider society. This central commitment to thinking for himself, while working with and alongside others, was at the heart of the Ethical movement to which he lent support for almost 40 years, and continues to animate organised humanism today.

Humanists International was formed in 1952 as the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU): a federation of the American Ethical […]

Richard Congreve was a devoted follower of Auguste Comte, whose positivist philosophies and ‘Religion of Humanity’ inspired Congreve to open […]

It is not because the believer in rational religion has not clear convictions that he will not shape them into […]

The notion that a man shall judge for himself what he is told, sifting the evidence and weighing the conclusions, […]