Humanism could (better) be honoured by reciting a list of the things one has enjoyed or found interesting, of the people who have helped one and of the people whom one has loved and tried to help. The list would not be dramatic, it would lack the sonority of a creed and the solemnity of a sanction, but it could be recited confidently, for human gratitude and human hopefulness would be speaking.

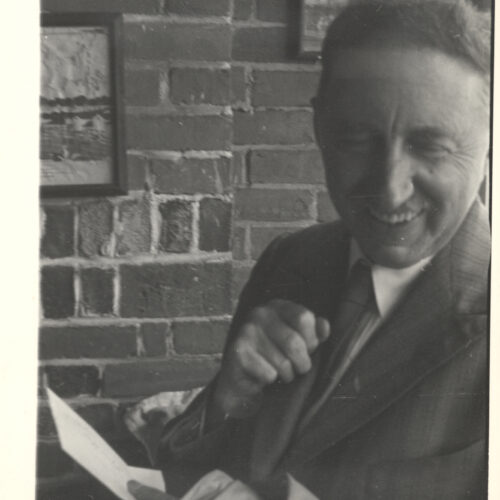

E.M. Forster, 1955

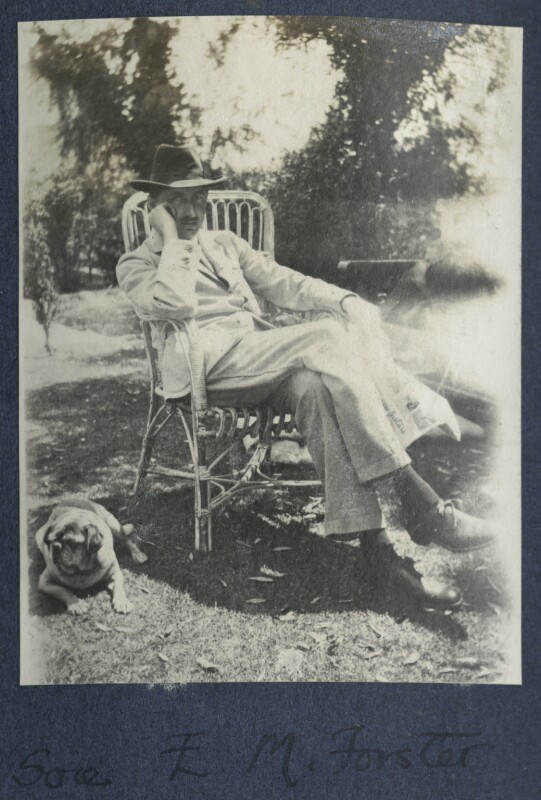

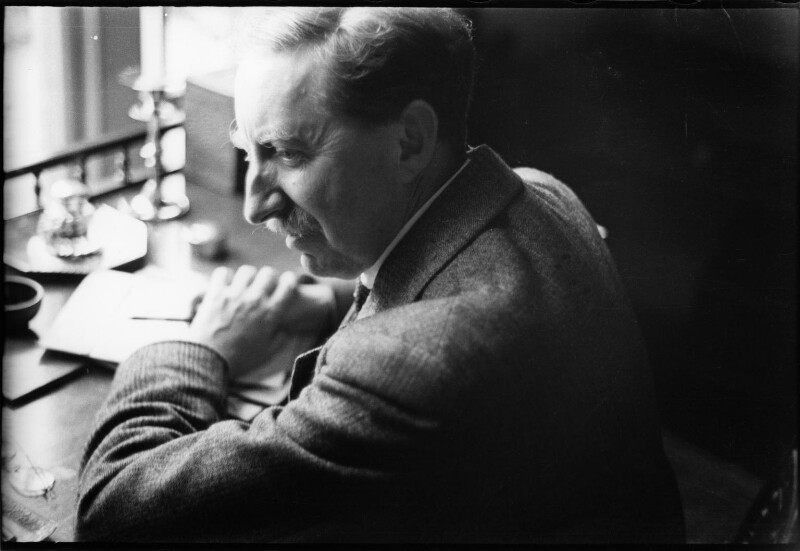

Edward Morgan Forster was a novelist, critic, and prominent humanist; a close associate of the Bloomsbury Group, and a longtime Vice President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK). Forster’s humanism suffused his writings and animated his life, grounded in empathy for others and the striving for happiness.

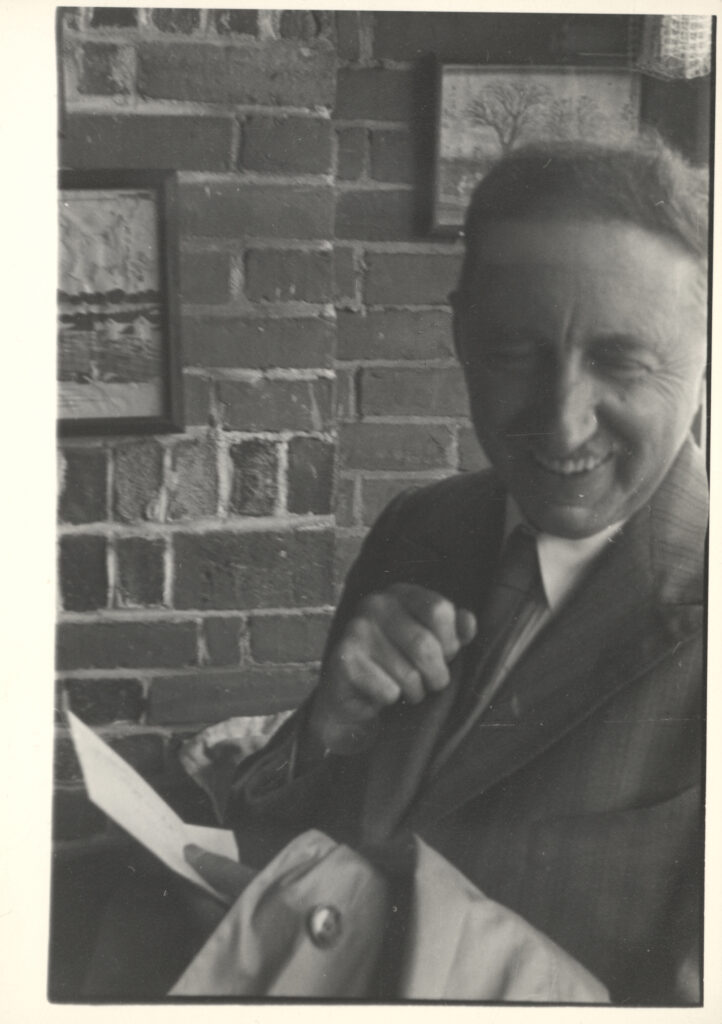

E.M. Forster was born on New Year’s Day 1879 in Marylebone, London to Edward Morgan Llewellyn and Alice Clara (Lily) Forster (née Whichelo). His father, an architect, died in 1880, leaving his wife and son enough to be well provided for. Later combined with a further inheritance, the two were ‘much more than merely comfortable’. In 1897, Forster went up to King’s College, Cambridge, where his influences included Nathaniel Wedd and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson. Here, Forster was made a member of the secretive and elite Cambridge Apostles, replacing another noted humanist and early president of Humanists UK, G.E. Moore.

During the early 1900s, Forster travelled in Italy, Austria, and Greece, and lived in Bloomsbury and Weybridge, Surrey. In October 1905, his first novel, Where Angels Fear to Tread, was published. In all, Forster wrote six novels, Where Angels Fear to Tread, The Longest Journey (1907), A Room with a View (1908), Howards End (1910), Maurice (1913, but published posthumously in 1971), and A Passage to India (1924). During the First World War, Forster joined the Red Cross, working in Alexandria as a searcher tracing missing soldiers. There, he began a relationship with Muhammad al-Adl, and published short journalistic pieces for Egyptian publications. He returned to England soon after his fortieth birthday, in 1919.

In 1930, Forster met Bob Buckingham, a policeman, with whom he maintained a relationship until his death. In 1932 he wrote: ‘I have been happy, and would like to remind others that their turns can come too. It is the only message worth giving’. It was during this decade that Forster became a visible presence in campaigns for civic freedom and social reform. In 1934, he was the first President of the National Council for Civil Liberties, and devoted his time – and pen – to a variety of progressive causes. In 1939, his essay What I Believe was published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press, giving expression to his deeply held humanist principles, including the vital importance of democracy, and the significance of human relationships.

Forster’s humanism was at the heart of his writing, which, along with every action of his public and private work, was described as being ‘surcharged with his love of humanity.’ For Forster, ‘A humanist [had] four leading characteristics — curiosity, a free mind, belief in good taste, and belief in the human race.’ In his novels and essays, these ideas and many others are explored, with the importance of human connection often front and centre. This was summed up in What I Believe, when he wrote: ‘One must be fond of people and trust them if one is not to make a mess of life’. A belief in the importance of our one and only life, and the duty to live it as well as possible, also found clear expression in Forster’s writing. After all, as he wrote in Howards End, ‘Death destroys a man, but the idea of death saves him’.

Forster’s thoughtful and compassionate humanism led him to hope for what he described as ‘an aristocracy of the sensitive’. This, he said, would be comprised of

the considerate and the plucky. Its members are to be found in all nations and classes, and all through the ages, and there is a secret understanding between them when they meet. They represent the true human tradition, the one permanent victory of our queer race over cruelty and chaos. Thousands of them perish in obscurity, a few are great names. They are sensitive for others as well as for themselves, they are considerate without being fussy, their pluck is not swankiness but the power to endure, and they can take a joke.

In 1957, Forster became a Vice President of the Ethical Union, and was active in efforts to combat anti-humanist bias at the BBC. Alongside other prominent humanists including Bertrand Russell, Julian Huxley, and A.J. Ayer, he was one of 30 signatories on a memorandum submitted by the Humanist Association, requesting that an advisory council be appointed to ‘help them with the presentation of humanism.’ Forster actively defended Margaret Knight (appointed a Vice President of the Ethical Union in the same year as Forster) in her own struggles to advocate for education without religion on BBC radio.

E. M. Forster died at the Coventry home of his friends the Buckinghams on 7 June 1970. After cremation, his ashes were scattered on the Coventry crematorium’s rose bed.

Tolerance, good temper and sympathy – they are what matter really, and if the human race is not to collapse they must come to the front before long.

E.M. Forster, What I Believe

In E.M. Forster: The Endless Journey, John Sayre Martin described Forster’s as ‘the voice of the humanist’:

…one seriously committed to human values while refusing to take himself too seriously. Its tone is inquiring, not dogmatic. It reflects a mind aware of the complexities confronting those who wish to live spiritually satisfying, morally responsible lives in a world that increasingly militates against individual’s needs. Sensitively and often profoundly, Forster’s fiction explores the problems such people encounter.

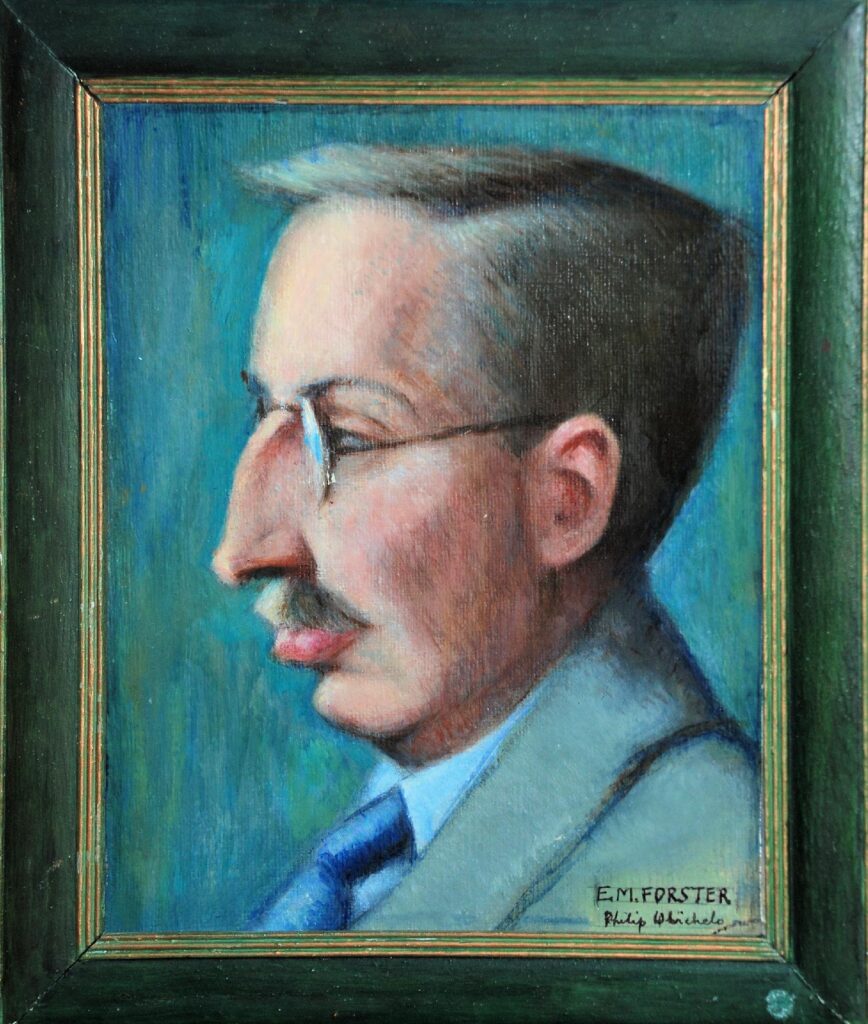

A powerful advocate of human rights, civil liberties, and the responsibility of human beings to one another, Forster exemplified the humanist approach in his life and art. A vocal supporter of the British Humanist Association, and an influential voice for its causes, he did much to give expression to those values which remain at the heart of Humanists UK today. Though unable to be open about his sexuality during his lifetime, Forster’s portrait, painted by his cousin Philip Whichelo, now hangs in the library at Conway Hall, a gift from GALHA (now LGBT Humanists).

From the outset IAS aimed to have an open approach to prospective adopters irrespective of their race, religion and creed, […]

The difference and variety of our human family more and more seems to me to be a wise provision that […]

Thomas Henry Huxley was a man of science, a biologist, and educator. He helped to transform scientific study into a […]

The courage and steadfastness which lead thoughtful people to declare themselves openly Rationalists in face of conventional social pressure is […]